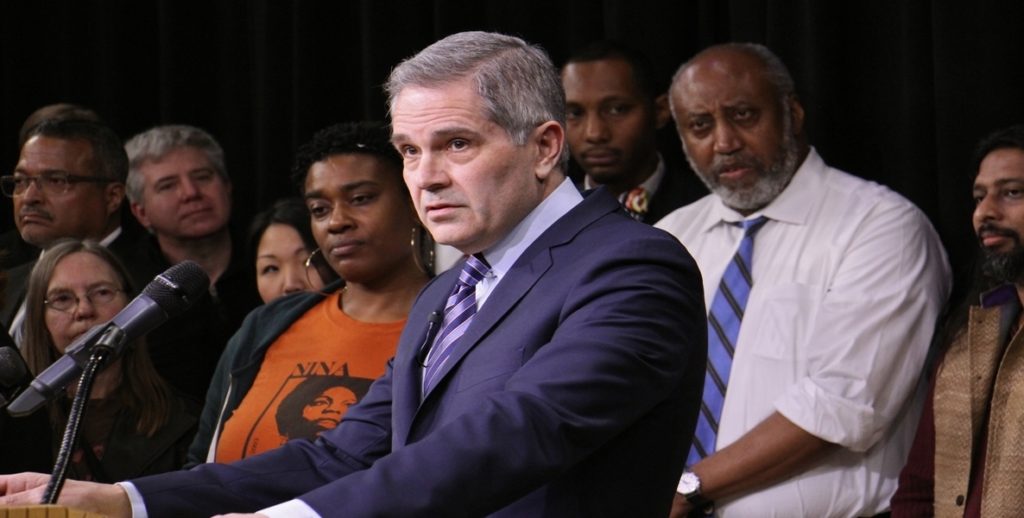

Larry Krasner, the Democratic nominee and—given our lopsided voter registration numbers— likely our next District Attorney, is not alone. Across the country, progressive prosecutors have been sweeping into office—many, like Krasner, thanks to the largesse of billionaire philanthropist George Soros.

Described by African-American lawyer Michael Coard as “the blackest white DA candidate ever,” Krasner sounds a great deal like Baltimore State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, Cook County (Chicago) State’s Attorney Kim Foxx, and State Attorney Aramis Ayala in the Orlando, Florida area. Krasner wants to end mass incarceration and refuses to seek the death penalty. He has spoken out against stop-and-frisk police tactics and has advocated for sentencing reform. If elected, he also wants to revamp civil asset forfeiture and eliminate cash bail.

As Krasner readies himself for the campaign against Republican Beth Grossman, it bears wondering if there are lessons that an outsider like Krasner—a civil rights and defense lawyer who has never prosecuted a case—can take from the experiences of the aforementioned progressives, many of whom are experiencing significant pushback to their very similar reform agendas. It’s no surprise that much of the opposition the new wave prosecutors have encountered has been led by Fraternal Orders of Police, pro-death penalty victims’ rights groups, and elected officials leery of too much change, too fast.

To Krasner, such pushback from the establishment just might be a good thing. “What you’re seeing is a very good development in the arc of social change,” Krasner recently told me, identifying four phases of social reform. “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win. We’re at the ‘fight you’ phase, and the reason you’re having a fight is progressive DAs are winning. We are far along and coming to the finish line. For years these ideas wouldn’t have been considered in a political discussion.”

All the backlash faced by Ayala, Mosby, and the others? It’s to be expected. “The reason they are fighting back is the wall is falling,” Krasner says. “It’s about to fall. Change is always difficult but change is coming.”

The case study of what Orlando’s Ayala has gone through is particularly relevant for Krasner, given the similarities between the two. Both candidates received financial support from Soros. Soros, who has contributed over $10 million to progressive prosecutors seeking criminal justice reform, gave $1.4 million each to Krasner and Ayala.

Like Krasner, Ayala, who has worked both as a public defender and a prosecutor, opposes the death penalty. However, when she ran for office, Ayala did not disclose her stance on capital punishment, despite numerous questions on the subject. Rather, she waited until March to say she would not pursue the death penalty under any circumstances, on the grounds that it has no public safety benefit; does not make police safer; is costly; is not a deterrent, and fails to provide closure to victims’ families. When she refused to seek death in the case of Markeith Loyd, who was charged with the murders of his pregnant girlfriend and an Orlando police officer, Gov. Rick Scott pulled the Loyd case from her and removed her from a total of 23 murder cases “in the interest of justice,” reassigning them to another state attorney by executive order. Ayala sued Scott, arguing that the governor lacked the authority to make the move, which she said deprived her of her constitutional rights, and her constituents “of the benefit of their votes.”

“If there was any a case for the death penalty, this is the case,” Orlando Police Chief John Mina said in March, as reported in the Orlando Sentinel. “I’ve seen the video, so I know the state attorney has seen the video of [Loyd] standing over defenseless and helpless Lt. Debra Clayton and executing her.” Some families of homicide victims say Ayala shut them out, while others support her. Many of Ayala’s fellow state prosecutors have sided with the governor.

Florida is a leader in mass incarceration, and is ranked tenth worst in the nation in terms of its imprisonment rate. Until this year, the state allowed only 10 jurors to impose a death sentence; in March, the state passed a law requiring a unanimous jury recommendation before judges can impose a death sentence. With 27 people, the Sunshine State has the highest number of exonerations of death row inmates due to innocence, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The vast majority of the exonerated are people of color. It’s not surprising that Ayala has become a lightning rod; someone mailed a noose to Ayala’s office to express their displeasure with the top prosecutor.

Ayala isn’t the only progressive prosecutor to have encountered difficulty. Marilyn Mosby has met resistance in Baltimore, a result of the failed prosecution of six police officers in the arrest and death of Freddie Gray. Gray died from a severed spinal cord and a coma he sustained in the back of a police van, leading to unrest, protests and a state of emergency in Baltimore. After the charges, which included second-degree murder and manslaughter, were dropped or resulted in acquittals, five of the six officers filed a federal lawsuit for malicious prosecution, defamation and invasion of privacy against Mosby.

“One of the big challenges that progressive prosecutors face is we have a range of expectations for prosecutors that are in tension with each other,” says Stanford Law Professor David Alan Slansky, noting society wants them to be both dispassionate and courtroom advocates, to both uphold the law and reflect community sentiment. “Add to that the challenges of running the D.A.’s office itself, a large organization and it is difficult to turn it around.”

What can Krasner learn from what Ayala and Mosby have gone through? David Alan Sklansky, Stanley Morrison Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and author of “The Progressive Prosecutor’s Handbook,” says Krasner will have to walk a fine line. “One of the big challenges that progressive prosecutors face is we have a range of expectations for prosecutors that are in tension with each other,” he says, noting society wants them to be both dispassionate and courtroom advocates, to both uphold the law and reflect community sentiment. Both Ayala and Mosby tried to strike that delicate balance. “Add to that the challenges of running the D.A.’s office itself, a large organization and it is difficult to turn it around. It’s like steering a large aircraft carrier.”

According to Sklansky, there are two major things a reform minded prosecutor should look out for: “You need to avoid tunnel vision,” he says. “And you need to watch out for insufficient focus. You don’t want too much attention because it blows up in your face. If you don’t pay attention to high ethical standards and financial propriety, it doesn’t matter because your leadership will be ineffective. If you don’t pay attention to the issue of disclosure of exculpatory information and particular information relating to informants, everything else you do won’t matter and you wind up with a tarnished legacy.” And, he points out, that a reform-minded DA needs to have a plan in place to credibly handle shootings by police officers and deaths at the hands of cops and corrections officers, as “handling these investigations like other investigations doesn’t work.”

With that in mind, it is possible for progressive prosecutors to do all these things and still find themselves fighting to hold their office, Sklansky argues. Mosby, for example—who dealt aggressively with deaths at the hands of police officers—had no problems of financial impropriety or handling of exculpatory evidence. However, she did face a great deal of criticism due to rising crime rates, and the failure to land convictions for the officers in the Freddie Gray case. “It is important for progressive prosecutors ahead of time to think about how they want to be judged,” he says.

So what steps can a novice like Krasner take? According to Slansky, he’ll have to reach out and listen to other people, including law enforcement, to discuss the proper direction of policy reform, and really be interested in their perspectives. “Rank and file police officers know a lot and can play a constructive role in police reform,” Slanksy says. “That does not always happen, and police unions are not always proactive agents of reform.” But one reason police unions are potential obstacles to reform is they are not invited to the table when criminal justice strategy is discussed.

In addition, many cities have identity-based organizations of African American, women, Latino and other officers. Krasner, for example, has received the endorsement of the Guardian Civic League, an organization representing the interests of black officers in Philadelphia, which often disagrees with the F.O.P. on a variety of issues, including the decision by the local chapter and national organization to support Trump for president.

Each jurisdiction is different, and Orlando or Baltimore by no means offer the same environment as Philadelphia. After all, while Ayala must contend with a Republican governor with an open hostility to civil rights and people of color—not to mention Florida’s status as an oddball political state—Krasner would have an ally in Gov. Wolf, a Democrat and death penalty opponent who brought the state’s death penalty machine to a halt for now. And we cannot trivialize the role of Ayala’s race and gender in the backlash she has faced.

Soon, Krasner will have to deliver real reform and results. To do that, he’ll have to learn from the paths blazed by other progressive prosecutors and show off political skills he might not even know he has.

The FOP—which supported Trump for president and called Krasner anti-law enforcement following his May primary victory—made peace with Krasner, with Rep. Bob Brady brokering the meeting. Nevertheless, one can envision the issue of law enforcement and police abuse having the potential to dog Krasner in the way the death penalty has occupied Ayala’s time. This, in a city with no shortage of policing issues, and a bad history of police-community relations, from Rizzo and the MOVE bombing to stop-and-frisk and excessive force.

The cases of State Attorneys Aramis Ayala and Marilyn Mosby demonstrate the difference a DA can make, but also the limitations of the office. For all their power and discretion, DAs are not legislators. However, as the head prosecutor in the state’s largest city, Larry Krasner could position himself as a potent advocate for reform, someone who lobbies Harrisburg and works with other criminal justice stakeholders.

Is Krasner watching the trials and tribulations of other progressive prosecutors? I caught up with him to ask what his thoughts are on the matter. “My thoughts on the challenges are that change is hard,” Krasner says. He sees these changes through the prism of other social movements he’s been involved in, returning in conversation again and again to the tremendous challenges faced by the LGBTQ community he represented in San Francisco after graduating from Stanford Law School: “For 30 years, I represented LGBTQ activists around gay rights and HIV, and the fear that went around it. And guess what: We have gay marriage.”

All the backlash faced by Ayala, Mosby, and the others? It’s to be expected. “The reason they are fighting back is the wall is falling,” Krasner says. “It’s about to fall. Change is always difficult but change is coming.”

According to Krasner, pundits may wring their hands about the wisdom of criminal justice reform, but the people get the need. “Fundamentally, when 1 out of 3 black men are going to jail in their lifetime, people see the impact on their lives and their communities,” he says. “The accumulation of mass incarceration over all this time has brought us to a point where communities of color, poor people, and high information voters all get it.”

Krasner makes a passionate argument that, in effect, this election is about more than him. It’s about a national transformation. “When the Koch brothers and people on the Left agree, when Newt Gingrich and Van Jones are on the same page, then change has to come,” he says. “The legal profession is slow to change. It’s living in the 1970s, talking about mandatory minimums and the answer to drug addiction is more sentencing. Some of the old heads are talking stupid.”

One of the ways the times have changed, Krasner says, is that a new “unbeatable consensus” on the need for criminal justice reform has risen up. It consists of millennials, people of color and high information voters. All, Krasner maintains, are thoughtful on these complicated issues. To date, he’s been an outspoken outsider. Soon, he’ll have to deliver real reform and results. To do that, Krasner will have to learn from the paths blazed by other progressive prosecutors and show off political skills he might not even know he has.