Mayor Kenney in his 2015 campaign made an audacious pledge that many mayors were making around that time: to reduce pedestrian deaths and serious traffic-related injuries to zero, starting by cutting the number in half by 2026.

This concept — branded as Vision Zero — had begun to be popularized in the United States, starting in the 2013 New York City mayoral race, and was envisioned to be a whole-of-government effort by elected officials, streets and public works staff, transportation officials, police, public health agencies, and others to address every contributing aspect of these serious crashes.

RELATED: New art project aims to curb traffic accidents near a school in South Philly

The strategies for this typically fall into three buckets: engineering, education, and enforcement—with an emphasis on street reengineering as the most important medium to long-term strategy. But that’s been the area where the Kenney administration has arguably been lagging the most.

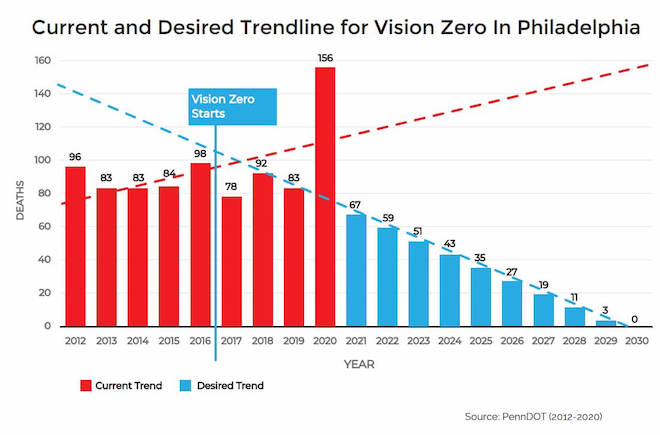

This week the City released its latest progress report on this goal, and the results are super dismal. It’s been reported already: 2020 was the worst year in recent history for crashes. The news can partly be blamed on the pandemic, but the trend line was headed in the wrong direction even before 2020—and it’s been clear for a while that the City’s efforts weren’t going to be sufficient to meet Candidate Kenney’s ambitious goal.

There are several reasons why this is the case—low city spending per-capita on streets, for one thing—but the bigger issue is about a governance failure on the streets reengineering front.

One of the iron laws of Philadelphia politics is that if you want to have less of something, put it under the control of the councilmanic prerogative system. Whether it’s housing, outdoor dining, bus lanes, bike lanes—you name it—once it’s under the sway of District Councilmembers, you are practically guaranteed to see less of that thing.

And that is exactly what happened to street design almost 10 years ago, in 2012, when under the initiative of then-Councilperson Bill Greenlee, City Council took over the power to approve lane alterations, like when a travel lane or a lane of parking is converted to a bus or bike lane. After that, the mileage of bike lane-striping per year fell off a cliff, and has plodded along at a sluggish pace ever since. That’s obviously inadequate to achieve the mayor’s stated goals.

Councilmanic prerogative over streets has created three basic problems. One is that the members pretty straightforwardly awarded themselves this power in order to never use it, or at least to use it less often than the Mayor’s Office would, if unencumbered by the Council ordinance requirement.

One of the iron laws of Philadelphia politics is that if you want to have less of something, put it under the control of the councilmanic prerogative system.

The less visible, but more damaging problem is that the Council-approval requirement puts a big damper on the quantity and ambition of projects that get dreamed up by the administration in the first place, because the administration is constrained by the political realities of what may be possible to get through City Council—by design, the more parochial of the city’s governing institutions. That damage is measured by the number of viable projects that never get proposed at all, which of course is unknowable.

And the third and most invisible problem of all is the impact of the 2012 governance change on the projects that are fully within the mayor’s power to do. There are still some street safety projects—like Washington Avenue for example—that the mayoral administration is allowed to do that do not involve repurposing travel or parking lanes.

But the mayor’s office doing anything even remotely controversial as a unilateral move comes with a big risk that Council could go even further in curtailing the mayor’s power, so there’s an incentive for the administration not to rock the boat too much. That’s had a chilling effect of essentially imposing councilmanic prerogative-type political dynamics even in situations where no Council sign-off is technically required, and this has all really trimmed the administration’s sails.

RELATED: What is councilmanic prerogative in Philadelphia?

Given these governance dynamics, it’s easy to see how Philadelphia’s political system could drastically under-produce the kinds of life-saving street alterations needed to meet Mayor Kenney’s ambitious goals, and fail to counter these disturbing pedestrian fatality trends. And zooming out, you can also see very similar political incentives at play with all of the issues that tend to live in the councilmanic prerogative basket, with similar poor outcomes.

For better results, the laws and governing structure need to change so the right decisions can be made at the right levels of government.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

RELATED

Guest Commentary: Protect pedestrians. It’s Good for the Earth