A teacher in a rowdy classroom calls her students to attention. Then she starts her lesson. Emboldened, her voice gets louder. And louder. And louder. By the time she’s shouting, the students have stopped listening. So she starts all over again — and the cycle continues.

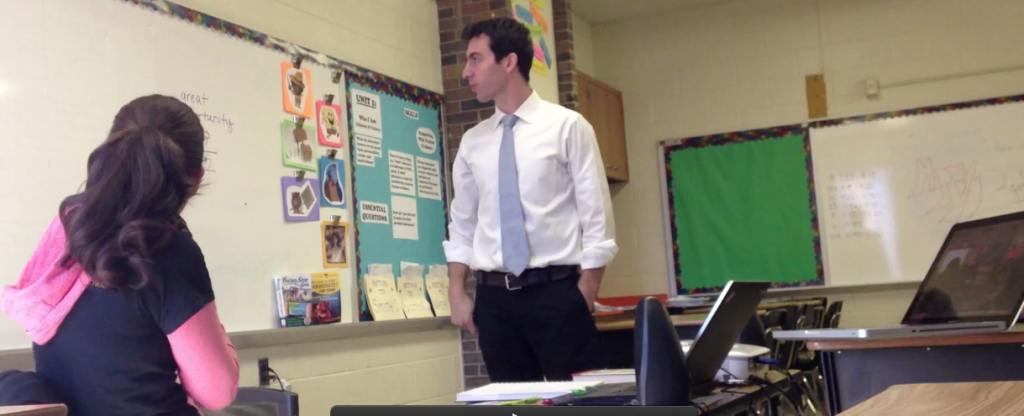

A few years ago, Paul Dean, a teacher coach and co-founder of Jounce Partners, observed a teacher doing just the opposite. She spoke quietly to her students, pulling them in to the discussion as they leaned forward to listen. Those students learned — and so did Dean. Later, he practiced and refined giving a quiet lesson in front of an imaginary classroom, so he could teach the method in coaching sessions Jounce operates in 10 Philadelphia schools (and one in DC).

It’s quite different from what Dean set out to do with Jounce cofounder Bobby Erzen. Dean and Erzen were roommates while working for Teach for America in New Orleans. They moved to Philly after Dean’s wife started law school at Penn, and founded the Student Leadership Project in 2011 to coach middle school students on leadership skills.

“The idea was to train this small group of students who would then go on to improve the school,” Dean says.

It worked, to a point. Three times a week, SLP taught a group of 6th through 8th graders public-speaking, networking, team-building and presentation skills. Then they followed them into the classroom to see how well they used those new skills to keep their peers on task. In classrooms with strong teachers, the students succeeded. But when teachers struggled, so did the student leaders. They themselves failed to stay focused for more than five to 10 minutes — one of the skills they were supposed to model for their classmates. And Dean and Erzen found themselves having to correct their own student leaders’ behavior.

“We found that the strongest teachers were already doing this leadership skills training informally,” Dean says.

That’s when Dean and Erzen changed direction. For the last two and a half years, they have focused on coaching teachers. Their new name — Jounce Partners — reflects their philosophy: Jounce is a physics term that means the acceleration of acceleration.

“We had these two things we were doing and we figured out that one of them had a greater impact,” Dean says. “I wish that discovery had come a little quicker.”

Dean and Erzen, both in their 20s, do not have a lot of classroom experience. They learn what they know through observations of successful teachers, and research, then create a process with action steps that they can share with other teachers. Jounce meets with teachers in its partner schools for 15 minute sessions three or four times per week to discuss a teaching technique, then model it in front of the classroom and observe the teachers putting the method to use.

“We’re not experts on great teaching but trying to be experts on great coaching,” Dean says. “Whatever administrators want their teachers to get better at, we spend a lot of time working on improving those skills.”

THE CITIZEN: Tell me about the Jounce Partners.

Bobby Erzen: The mission of the Jounce Partners is two-fold: The global vision and mission is to systematically create a way to build positive culture at all schools; a culture where all kids have a thirst for learning. To get there, the second mission would be transforming the schools that we partner with and figuring out how to disseminate these ideas and get other schools to adopt. Not many folks purely focus on culture as a catalyst for academic achievement.

Paul Dean: We are really focused on quality. We don’t want “urban schools” to be a separate category anymore. Those considered the best urban schools are falling way short of the best non-urban schools. The best urban schools have been celebrated a lot, and for good reason, due to positive strides. We were teachers in New Orleans before we started Student Leadership Academy (now Jounce Partners) in Philadelphia. New Orleans has been held up as as a way to do things differently in urban education, but we know even the best of those schools are still not schools that I would send my kid or where all the students graduate from college. We want kids to leave the schools that they are in with a true desire to learn, an intrinsic motivation to learn, and the characteristics that will help them succeed in college. It all starts with finding ways to build a strong school culture.

THE CITIZEN: What does a strong school culture looks like?

PD: We broke it down into school culture progression. The ultimate goal is to have a character-driven culture. This is a culture where you can basically take a kid from one environment and place them in a different environment, where learning is not valued in the same way, and they have internalized that value of learning so much that they are going to be successful in that environment even when there are distractions. That’s the ultimate goal of this character-driven culture. The progression along the way is norm-driven culture. We want students to perceive how all of their peers are focused on and care about learning. Any time a kid looks around the room we want them to think, Wow these kids in this classroom really care about learning and are focused on learning.

THE CITIZEN: How do you create a norm-based culture in a school?

BE: To create a norm-based culture every single teacher needs to hold the kids to the same expectations. For example, a kid might walk into one classroom where the teacher has high expectations for the students and in a second classroom the teacher has low expectations for students. In this situation there is little in the way of norm-based culture. In a school with a norm-based culture all teachers hold students to the same level of expectations.

PD: Creating this norm-based culture starts to change self-concept and that is what we need to get to. Changing self-concept to “I am a learner, a person who loves learning and is invested in learning.” We believe it is impossible to change that self-concept unless a clear norm-based culture exists first.THE CITIZEN: You work with school leaders, teachers, and students. Could you tell me how you work with each of these groups?

PD: Teachers are key because they each set their own norm in each of their classrooms. So we do teacher coaching at each of the schools we work with. We use a specific coaching model that relies on high frequency so we meet with teachers 3 to 5 times per week. The goal is to help teachers develop habits that they can use in the classroom. We also help school leaders, principals, and vice principals use the same coaching model when they work with individual teachers. Our work with kids is in more of an R&D phase. Working with teachers gets us a norm-based culture but getting kids to internalize that culture so they’re going to take it with them when they leave the school is in some ways a black box. There are a lot of people doing research trying to figure this out. We are taking aspects of the research and putting it into practice to see what works.

THE CITIZEN: Have there been any surprises as far as what works and what doesn’t work?

PD: We made a big shift from spending most of our time working with kids to working more with teachers. The goal of building a school-wide norm-based culture has not changed. We just learned that teachers are the first step for building that culture. We see schools that want to get to this character-driven place so they spend a lot of time trying to teach character. But if kids are getting different messages from their peers or teachers then it will not be successful. We did not have this in our mind when we started.

THE CITIZEN: What challenges are there to being education innovators in Philadelphia?

BE: Coming from New Orleans, which is considered the testing lab for innovative education ideas, there was a lot of money flowing there for innovative education programs. It was easier to get funding there than in Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, the overwhelming culture is not first-step innovation. This is not to say there are not people in Philadelphia interested in innovation, but it is a small group. Being a small group does make it a tight knit group. When you get started and connect to the start-up community, you find that others in the network are willing to help out.

THE CITIZEN: What do you see in the future for the Jounce Partners?

BE: Later this spring, we’ll be working with 8 more schools in D.C. Within the next six months, we’ll probably be expanding our staff to keep up with the additional demand.