[Editor’s note: This article originally ran in March, during Democratic primary season. We are re-running it today in anticipation of Joe Biden’s acceptance speech tonight for his nomination to be the Democratic candidate for president.]

Many of us who live and die politics spent a good part of the early Democratic ![]()

Moreover, in retrospect, the breathless tone (Elizabeth Warren’s passionate takedown of the Senate filibuster comes to mind) suggested the Democrats had taken the bait. By reacting to Trump with anger and ideology, the candidates who sought to succeed him ignored the self-evident change the electorate just may be hankering for.

Get ready, progressives, to flog me: The problem isn’t Trump’s political ideology. He has no core political beliefs; he is as transactional a political figure as we’ve seen.

If Trump believed Medicare for All could get him reelected, he’d recruit Bernie Sanders to replace Mike Pence as his running mate. In fact, you can actually make an argument that he’s done at least a couple progressive things: The First Step Act and Opportunity Zones, which unlocks more capital into distressed inner-city neighborhoods than his predecessor ever did, for example.

The problem is Trump himself, his indecency, his lack of empathy and character. Turns out, there was one candidate who saw or—more accurately—intuited that.

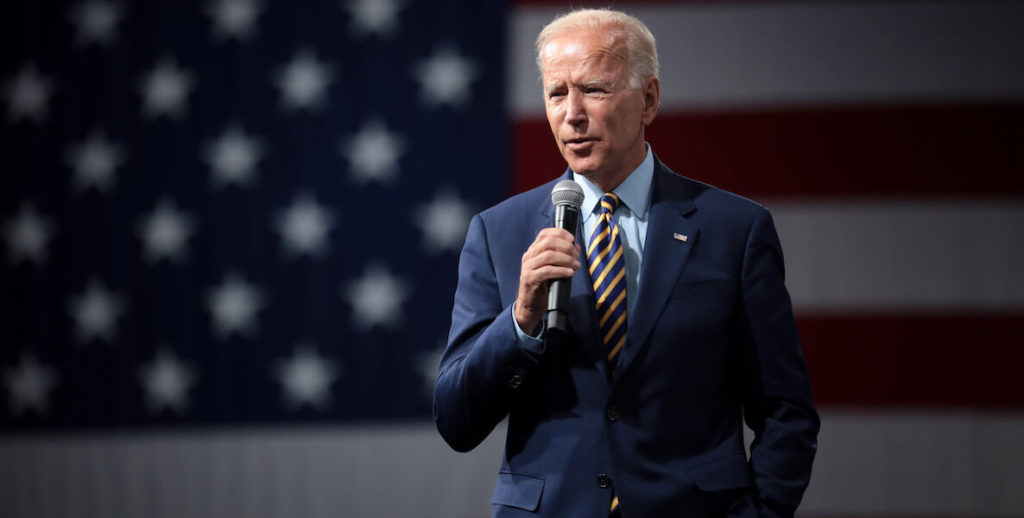

No, the problem is Trump himself, his indecency, his lack of empathy and character. Turns out, there was one candidate who saw or—more accurately—intuited that. Joe Biden might not have grand new ideas, and, yes, he devolves into weirdness, like when he jokingly called a questioner at a town hall after his disappointing performance in the Iowa caucus “a lying, dog-faced pony soldier,” citing, when pressed, a non-existent John Wayne movie for the odd phrase. Many of us saw that and wondered, exasperated, What’s he thinking?

Well, turns out, by just being himself, ol’ Joe may have known what he was doing all along. He may have sensed that the electorate wasn’t in search of highfalutin policy, slick style or talk of revolution. Instead, Joe Biden, a 40-year player on the D.C. political scene, gave us the least likely candidate of change we’ve ever seen: Someone, for all his shoulder massages and verbal gaffes, who embodies in his very being decency and empathy.

For me, the first inkling of this came in a town hall just before the pivotal South Carolina primary, when Biden spoke to Rev. Anthony Thompson, whose wife, Myra, was one of nine murdered by a white supremacist during Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston.

The exchange is stunning for its emotional intelligence, its empathy, its authenticity. In his raw feeling, Biden rivals RFK’s ability to heal an audience by laying bare his own pain.

Watch it and you tell me if the tone isn’t precisely right for these coarse times, and the perfect answer to Trumpism:

Of course, by the time Biden was saying these words, many of us had already given up on him, because the oft-stumbling candidate had failed to excite.

But Rabbi Michael Beals, of Wilmington, Delaware’s Congregation Beth Shalom, was keeping the faith. Over a year ago, the Biden campaign had released a first-person account from Beals of a long-ago encounter with then-Senator Biden. The piece found its way into the Jewish press, but went no further.

Beals turned a long-ago interaction into a meditation on what America needs at this moment: A mensch, Yiddish for “person of integrity and honor.” More than ever, Beals argues, we need to be driven by the menschkeit philosophy, a selfless, innate compulsion for doing the right and decent thing.

Empathy, Beals says, is the highest level of emotional intelligence, and is therefore fundamental to menschkeit. Yes, he concedes, Biden misspeaks, but it’s never born of nastiness.

Beals’ thesis stuck with me as I burrowed through candidate white papers and watched rallies on C-Span. Then, after seeing Biden’s exchange with the reverend before the South Carolina primary, and reading about how he gives out his private cell phone number to those who have lost loved ones, as he has, and those who stutter, as he has, I reached out to Rabbi Beals to explore his Menschkeit postulate.

“I have been thinking of this for some time,” Rabbi Beals told me. “Because of the peculiarity of our governmental system, the head of state and the head of the government is the same person. In Israel, you have the president and the prime minister. Same in Japan. Here, we expect two things from our president. He or she should be a wonderful role model and be good at politics. We want our president to not only be successful, but be someone our sons and daughters look up to and wish to emulate. That’s menschkeit.”

In 2004, Beals was a young rabbi, new to Delaware by way of Southern California. He found himself navigating the streets of Biden’s Claymont, Delaware, where Biden had grown up—“a woebegotten area” Beals recalls today—in search of the home of the recently-deceased Mrs. Greenhouse.

She lived in rent-controlled senior housing, and Beals had been dispatched to lead a group of ten Jewish adults in a minyan service recitation of the Mourners’ Kaddish. Once there, it was clear that Mrs. Greenhouse’s tiny apartment wouldn’t accommodate that many guests, so the service moved to the basement laundry room.

During the prayer, the door opened, and into a senior high-rise laundry room walked Delaware’s senior senator, his head bowed.

Afterwards, Beals introduced himself to Biden, and asked why he was there. “Listen, back in 1972, when I first ran for Senate, Mrs. Greenhouse gave $18 to my first campaign, because that’s what she could afford,” Biden said. “And every six years, when I’d run for reelection, she’d give another $18. She did it her whole life. I’m here to show my respect and gratitude.”

Beals explained that, in Judaism, the number 18 stands for something. Its numbers spell out the Hebrew word chai, as in “to life, to life, l’chayim!” “There was no press there that day,” Beals told me. “That’s menschkeit, when you do the right thing and there’s nothing in it for you. Being a mensch is non-transactional. There’s no quid pro quo for being decent and good.”

If there is an animating idea behind Biden’s candidacy, it’s that the soul of America needs saving.

Beals has had other experiences with Biden through the years, like the time a congregant who was a big Biden donor had a photo booth at his son’s bar mitzvah so guests could get their photo taken with the senator. “I was raised in L.A., where we were told you don’t bother celebrities,” Beals recalled. “So I didn’t go over to the booth, but Senator Biden saw me and came bouncing over like a puppy dog. ‘Hey buddy, don’t you want to get your photo taken with me?’ He put his arm around me, and you could just feel his big-heartedness.”

Empathy, Beals says, is the highest level of emotional intelligence, and is therefore fundamental to menschkeit. Yes, he concedes, Biden misspeaks, but it’s never born of nastiness. “People see themselves in Joe, because he sees them,” he said.

If there is an animating idea behind Biden’s candidacy, it’s that the soul of America needs saving. Biden says so in every stump speech; in a time when there is so much anger politically and so much angst during a pandemic, Biden, who has lost a wife, a daughter and, most recently a son, talks in a whisper to hushed crowds about the power of healing.

To Beals, that is fitting. Because this may be the one election where the policy papers and the flourishes of rhetoric are besides the point. “There’s a lovely Yiddish phrase, Guttena Neshuma,” Rabbi Beals said. “That means good soul. That’s Joe, and it’s also what we need, all of us. A restoration of our soul.”

It’s election season in Philadelphia. Are you all set to vote?