By all accounts, the post-pandemic period in the U.S. is characterized by a remarkable resurgence in advanced manufacturing — a response to such challenges as rising geopolitical tensions, the climate crisis, and supply-chain vulnerabilities. This transformation, which we have termed the “industrial transition,” is being catalyzed by increased federal spending — notably, via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the CHIPS and Science Act. Both acts confront these disparate threats by focusing on two key objectives: reshoring production and accelerating decarbonization.

Companies are capitalizing on this moment, spurring private investments in the construction and expansion of a vast array of advanced manufacturing facilities. To track this progress, the White House launched Invest.gov, providing an interactive map showcasing private-sector investments that have been mobilized by President Biden’s agenda.

As of June 2023, the White House map revealed a total of 258 projects, amounting to a staggering $449 billion across states in four key sectors: batteries/electric vehicles, semiconductors, biomanufacturing, and clean energy. Particularly noteworthy are the batteries/EV sector, leading with 43.4 percent of projects; and the semiconductors sector, accumulating the highest dollar amount of $212 billion, despite having the fewest private investments.

While Pennsylvania possesses a diverse and historically strong manufacturing base, it currently does not rank among the top 10 states in any of the targeted sectors.

The subnational distribution of these investments is establishing a new industrial geography in the country. Texas has emerged as the leading state in attracting private investments, with approximately $76 billion, followed closely by Arizona, New York, and Ohio. Texas and Ohio stand out for their strong performance in most sectors, with Texas ranking among the top five states for all sectors except biomanufacturing, and Ohio excelling in all sectors except clean energy (though it still holds the ninth position in this area).

Given the scale and scope of the industrial transition, Drexel University’s Nowak Metro Finance Lab has undertaken an assessment of the information assembled by the Biden administration in order to evaluate Pennsylvania’s performance to date. The results are sobering. While Pennsylvania possesses a diverse and historically strong manufacturing base, it currently does not rank among the top 10 states in any of the targeted sectors.

The past, however, does not need to be prologue. We recognize and applaud efforts by Governor Josh Shapiro and the state legislature to get Pennsylvania back into the industrial policy game, with new or expanded tools and incentives. By examining projects, sectors, and states of similar population size, our aim is to help Pennsylvania better participate in the nation’s economic transformation and position itself as a key player in the nation’s sustainable and competitive future.

Is Pennsylvania where it should be?

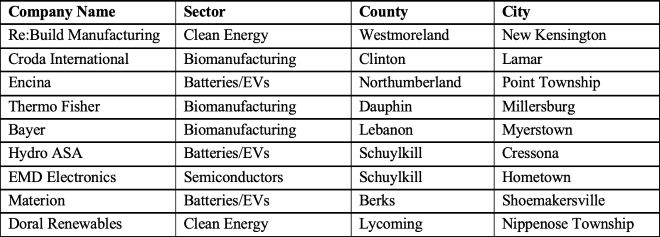

The White House map showcases nine deals in Pennsylvania. Three of these deals are in biomanufacturing, three are in batteries/EV, two are in clean energy, and one involves semiconductors.

Table 1: Manufacturing Deals in Pennsylvania

Given that Pennsylvania is the fifth most populous state in the country, with major metropolitan areas such as Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, we would expect the levels of private investment to be substantial. But in comparing Pennsylvania with states of similar population size, as done below, we find that Pennsylvania is generally lagging such states as Ohio, Michigan, North Carolina, and Georgia.

We further find that Pennsylvania lags in private investment relative to those states when we break our analysis down by particular industries. As shown in Figure 1, we found the top 10 states by private investment (in dollars) in the four industries represented on the White House map. Pennsylvania does not make this list in any of these industries, while Ohio, Michigan, North Carolina, and Georgia repeatedly show up.

Figure 1: Top 10 States in Total Private Investment for Four Industries

Why is Pennsylvania not seeing the same levels of private investment?

The White House data show that private investment in key industry sectors is bypassing Pennsylvania. In some respects, this poor performance shouldn’t be surprising. Once vaunted for its economic development prowess, the state has seen a radical deterioration in its ability to compete for next-generation industries and companies. As the Brookings Institution discussed last year, over the last 15 years, “budget-cutting, legislative gridlock, and neglect have left Pennsylvania’s innovation programs and platforms in a state of decline.”

To dig deeper, we used the White House data to compare Pennsylvania’s performance with that of an adjoining state, Ohio. Incredibly, Ohio has attracted at least five times more private investment than Pennsylvania, even after taking out the $20 billion production of Intel’s semiconductor facility near Columbus. Through an analysis of the private investments in Ohio and Pennsylvania in the White House data set, we highlight three key takeaways.

First, states like Ohio and Pennsylvania have different starting positions.

Pennsylvania and Ohio represent different starting positions within these key sectors of the industrial economy. As we discussed last year when regions competed for the Build Back Better Regional Challenge, geographies across the country represent ecosystems with distinct assets and advantages to cultivate growth in key industrial clusters. Pennsylvania and Ohio have similar historical legacies of strong industrial bases from the 20th century, but these bases have adapted differently to evolving and emerging industrial sectors. For example, with increasing momentum behind battery/EV production, Ohio’s legacy in car manufacturing has propelled the state as a key manufacturer along the “Battery Belt” stretching from Michigan to Georgia. Meanwhile, Pennsylvania, as the Brookings Institution report discusses, has struggled to amplify the state’s innovative clusters in life sciences, chemicals, and plastic/rubber products.

While investments in EVs and batteries are somewhat expected because of Ohio’s long tradition in the automotive industry, the state is also emerging as a hub for chip manufacturing and solar panel production, demonstrating its ability to stake out a position among rapidly reshoring industries. Pennsylvania has the innovative assets to similarly take ownership within new markets, but it is not translating to the same level of private investment.

For example, in a sector like biomanufacturing, three of the 46 deals represented on the White House map are located in Pennsylvania. However, these deals are the lowest in private investment dollars relative to the other 43 deals. This might be because many of the biomanufacturing investments on the White House map represent new construction in the pharmaceutical or biotech space, whereas Pennsylvania’s biomanufacturing deals reflect expansions in technology or existing facilities within life sciences and specialty chemicals.

Second, Ohio has been more active in marshaling resources and incentives than Pennsylvania.

Ohio has demonstrated a more active approach in marshaling resources and incentives compared with Pennsylvania. Specifically, JobsOhio, a private, nonprofit corporation serving as Ohio’s economic development organization, has been successful in leveraging assets and resources for a greater impact, while Pennsylvania has struggled to bring together several stakeholders to facilitate deals. Since the passage of IRA and CHIPS, JobsOhio has supported at least seven companies through a range of grants and assistance programs for onshoring and development in Ohio.

Among the nine deals that the White House map identified in Pennsylvania, it has invested in two — the Re:Build Manufacturing deal in the greater Pittsburgh area; and the EMD Electronics deal in Schuylkill County. Other deals, like Doral Renewables and Encina, have also received state attention. But otherwise, Pennsylvania seems relatively lacking in state resources and incentives. At the announcement of the $81 million Re:Build Manufacturing deal, Governor Shapiro acknowledged this gap by noting that states such as Ohio, New York, and New Jersey are committing far more resources than Pennsylvania to these kinds of economic development initiatives. “We need to catch up,” he said.

As the Brookings Institution discussed last year, over the last 15 years, “budget-cutting, legislative gridlock, and neglect have left Pennsylvania’s innovation programs and platforms in a state of decline.”

JobsOhio’s effectiveness lies in its ability to provide a seamless experience for companies by acting as a one-stop shop that connects them with relevant stakeholders and offers a diverse range of services that can be tailored to their specific needs. Numerous companies that recently invested in Ohio have collaborated with JobsOhio, with six of them receiving grants; SEMCORP has participated in the site authentication program for location selection; and Amgen has received assistance to develop a talent recruitment strategy. Moreover, JobsOhio works closely with six regional partners and numerous local economic development organizations throughout Ohio to ensure swift and effective fulfillment of businesses’ needs. Additionally, supported by private funding, JobsOhio is able to make long-term commitments and promptly address the requirements of businesses and communities.

This powerful combination of statewide coordination, diverse services, and flexible financial resources positions JobsOhio to effectively support and drive economic growth in Ohio. This shows that with the right strategy, states can leverage their funding for higher levels of investment — and even with limited funding, Pennsylvania has this potential. For example, the Re:Build Manufacturing deal stands out as a collaborative effort that drew funding from various local, private, and philanthropic sources, in addition to the state. A leading stakeholder in the deal, the Regional Industrial Development Corporation, commented on the deal in the Pittsburgh Business Journal: “When state and regional leaders band together as a united front and present aggressive incentives packages, the region can be a formidable force … [This deal] can be the first of many more wins if the lessons learned from this success story are replicated so the region can compete effectively to attract the economic activity and jobs that revitalize communities.”

Third, the deals in Ohio reflect strong coordination across urban, suburban, and rural assets to bolster ecosystems regionally; such coordination is lacking in Pennsylvania.

The interplay between large manufacturers, small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), research universities, community colleges, state and local governments, and infrastructure and energy providers creates regional ecosystems that, when coordinated, maximize economic growth. These assets are spatially spread across the urban-rural continuum — many advanced research universities typically locate in more urban settings and logistically connect to proximate suburban or rural industrial sites. This spatial and economic dynamic is largely found in White House deals for Ohio, as many of these corporations cite strong partnerships with educational institutions and draw from urban ecosystems like Columbus and Toledo.

For instance, Intel wants to take advantage of the proximity to the Ohio State University, a renowned urban institution that produces a significant number of engineering graduates whom Intel can recruit. The company has pledged $100 million to establish collaboration in the region. The central location of Columbus facilitates the smooth flow of supplies and shipping of finished chips.

SEMCORP strategically chose the Sidney, Ohio, location because of the state’s impressive commitment to vocational education and readiness for large-scale projects. According to SEMCORP’s vice president: “We were very impressed by all the workshops, all the machinery they have and the way they encouraged kids who might want to work with their hands or who were interested in trade professions … This is not just something Ohio talks about. They’re actually doing it.” Additionally, companies such as Invenergy and Amgen have established partnerships with local schools, universities, and community events in Ohio to enhance workforce support and industry training programs.

In Pennsylvania, the companies reflected in the state’s nine White House deals are mostly located in more rural counties (the one exception is Re:Build’s New Kensington site, located in a suburban county within the Greater Pittsburgh region), connected along the highway network to assets in State College (home to Penn State University) and Harrisburg (see Figure 2). Most of these deals represent expansions of existing companies in rural manufacturing towns, many of which saw significant decline when industry left in the 1970s. We find that manufacturing is still the largest industry for most of these counties (manufacturing is the largest or second-largest percentage of employment for eight out of nine of these sites; see Table 2). While it is a positive sign that these companies are expanding their existing bases in these towns, our team struggled to understand how they were leveraging nearby educational or research assets.

Figure 2: Map of Pennsylvania’s Manufacturing Deals

Table 2: County Details of Pennsylvania’s Manufacturing Deals

Next steps for Pennsylvania

Our analysis sheds light on the role that states can play in leveraging the new, bottom-up industrial policy set forth by the Biden administration. While there is much discussion of federal industrial policy, the reality is that the resurgence in advanced manufacturing is being delivered by a new kind of industrial federalism. It has become clear that states are critical in the delivery of advanced industry projects and initiatives; they can amplify or disrupt their regional markets to grow such industries.

While we focused on Ohio in our state comparison, it is not the only state effectively leveraging resources to attract such growth. Pennsylvania can learn many lessons from states with promising models, such as New York, North Carolina, Michigan, New Jersey, or Virginia, to develop its strategy and realize its economic potential.

Based on a preliminary comparison, we suggest that Pennsylvania design and invest in a three-pronged statewide strategy that builds on the governor’s 2023–24 budget proposal, which encompasses an impressive $481 million for the Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED). DCED secretary Rick Siger notes: “This budget is a crucial investment in Pennsylvania’s economy and lets us be more aggressive in attracting and retaining businesses and strengthening our communities.”

Chellie Cameron, president and CEO of Greater Philadelphia’s Chamber of Commerce, further elaborates: “We hope to build on this momentum through subsequent state budgets to firmly establish Pennsylvania as an inclusive economic leader.” DCED’s investments in economic competitiveness include $20 million for the new Historically Disadvantaged Business Program and a much-needed $13 million increase for Pennsylvania First, which will maximize leverage in upcoming investment deals. The Pennsylvania First program was allocated $33 million in this year’s budget, reflecting a 65 percent increase from last year’s budget and a 175 percent increase from the FY 2020–21 budget. (These figures were calculated from Pennsylvania’s previous enacted budgets, which can be found at www.budget.pa.gov).

Our three-part strategy is as follows:

-

- Target growing manufacturing clusters that align with the state’s competitive advantages.

Pennsylvania needs to leverage the distinct competitive assets and advantages of disparate parts of the state. The industrial transition reflects macro-level forces that are pushing the economy toward specific manufacturing sectors that support national security and clean energy. What are the core industries in Pennsylvania that can fit into this, and how do they leverage the state’s unique mix of innovation assets, supply chains, and manufacturing companies? Defense procurement adds another layer to this; according to a Department of Defense analysis last year, Pennsylvania received $13.4 billion in FY 2021 for defense contract spending. The governor can use the $5.6 million allocated for the Strategic Management Planning Program and Municipal Assistance Program to help local governments strategize and plan around an inclusive vision for the state.

Such planning should particularly bring key industry representatives to the table who have a clear sense of how the next-generation economy is developing. Furthermore, the $13 million increase for Pennsylvania First can be used to facilitate investment and job creation specifically in Pennsylvania’s competitive industries. The state should map out where its key innovation assets, supply chains, and manufacturing bases are located throughout the state, in order to ensure that each region is sufficiently networked during this economic transition.

-

- Maximize private, philanthropic, and public funding to drive business growth in key clusters.

To maximize funding across various stakeholders, the state needs more investment in the Keystone Communities Program or the Partnerships for Regional Economic Performance to encourage public-private partnerships and regional coordination. The creation of a new Office of Transformation and Opportunity, a one-stop shop for coordinating state agencies, will be helpful in speeding up the approval process of business reviews for economic incentives. States such as New York have a promising model to achieve this. Starting in 2011, New York established Regional Economic Development Councils, in which each regional council builds on the knowledge of local leaders to help direct the state’s investment strategy. New York’s success has inspired states such as California and Indiana to adopt this model.

-

- Strengthen partnerships with regional public and private resources, and across rural manufacturing towns, suburban municipalities, and urban tier 1 universities.

To strengthen connections, from manufacturing facilities to innovative R&D, more investments similar to the $13 million for the Manufacturing PA Initiative, a $1 million increase from last year, will connect Pennsylvania’s universities with local businesses and workforce. The state’s investment of $20 million for the Historically Disadvantaged Business Program will also better integrate Pennsylvania’s rural industry into regional ecosystems. Ultimately, the state needs to go further, adapting the best models emerging in the U.S. and globally. With federal, state, and corporate funds, for example, St. Louis, Missouri, is establishing an Advanced Manufacturing Innovation Center to serve the needs of Boeing and its suppliers in the defense aerospace sector, explicitly modeled on an applied research campus perfected in Sheffield, England.

Overall, our suggested strategy would organize and enhance Governor Shapiro’s policy agenda so that Pennsylvania can more actively participate in the industrial transition. We should consider the expanded resources appropriated to date as a down payment on future economic initiatives and transactions in Pennsylvania. If it can lay out a clear vision and focus to channel these investments, Pennsylvania can play a critical role in delivering relevant, targeted, and timely efforts that deliver on the modern industrial vision for the U.S.

Bruce Katz is the founding director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Avanti Krovi and Milena Dovali are research officers, and Mandi Lee is a graduate research analyst at the Nowak Lab.

This article was originally posted on September 12th on the RealClear Pennsylvania website (How Pennsylvania Fares Amid the U.S. Industrial Transition | RealClearPennsylvania).