In December, when the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court ruled that the much-disputed Christopher Columbus statue in Marconi Plaza in South Philly — you know, the one that’s been covered up since summer of 2020 by a wooden box subsequently painted like an Italian flag — would be set free from its plywood cage, it made me think about my hometown.

Franklin, Tennessee — a city of about 80,000 people, 22 miles south of Nashville — bears little resemblance to Philly in virtually any way … except that it, too, has struggled in recent years with how to deal with a controversial statue. This hardly sets the town apart; surely, most every place in America has grappled or will grapple with this. But Franklin’s solution might give our city something to think about as we move forward with the freshly unboxed Columbus.

First, though, a refresher: The 147-year-old statue of the Italian explorer — a Centennial gift to the city from Italy in 1876 — was one of many Columbus statues around the country that came under fire during protests for racial justice after the murder of George Floyd. (Across Broad Street from Columbus, in the eastern half of Marconi Plaza, is a statue of Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, the 19th-century Italian inventor and electrical engineer who created the radio — and won a Nobel Prize for it.)

One faction called for the statue to be pulled down in light of the atrocities Columbus committed toward indigenous peoples. Another, led by lawyer George Bochetto, argued this was cancel culture run amok, “a grudge-match” against the Italian Americans who saw the monument not as a celebration of oppression, but as a historic emblem of their heritage.

Things got ugly. Protests were met with counterprotests, which included, alarmingly, “mobs of White men with baseball bats and hammers,” ostensibly ready (hoping?) to defend the statue. To leave the thing up was unsafe, the City declared, and as plans for its removal began to be formalized, they boxed it up for the meantime. Then came the lawsuit, filed by Bochetto, representing the Friends of Marconi Plaza. Rather than remove Columbus, Bochetto posited in the Inky, why not add another statue that honored the indigenous people left out of this narrative?

Enter the Citizen’s Larry Platt, who decided to write about this fight, and what it said about the absolute intractability of this moment in time. He made his own case for dual statues, pointing out that he’d even proposed something similar four years earlier, with the problematic statue of Frank Rizzo, formerly stationed in front of the Municipal Services Building.

But I’ll be honest: This struck me at the time as a fairly weak solution. (Although not as weak as the Commonwealth Court’s recent suggestion that the City simply use a plaque to change the “message” of the Columbus statue.) After all, hadn’t New Orleans’s Mayor Mitch Landrieu given us all the language and reasoning and inspiration that we’d ever need back in 2017 when he took down the last of his city’s towering Confederate generals?

Furthermore, I liked the idea of replacing Columbus with Caroline LeCount, as historians Judith Giesberg and Lori Aument suggested back then, or maybe with a monument of a young, newly-arrived Italian immigrant family, as New Haven, Connecticut, did. I liked the idea of following Landrieu’s lead, of plucking out Philly’s offending statues and sending them to a museum or monument graveyard somewhere. Anything short of that would continue to send the wrong message about what we value, about what story we choose to cling to, about who we want to be now, today. This is what I believed. Firmly.

Then I went home for a visit.

Old Story, New Statue

In Franklin, the problematic statue is a 37-foot-tall monument in the town square which features — I’m sorry to tell you — a Confederate soldier perched up top. Unlike New Orleans’s statues, it does not honor a general, or even a named entity. (The statue’s nickname is Chip, thanks to a chip in his hat.) Growing up, I wrongly perceived this monument as commentary on war itself — mostly because the anonymous soldier always looked to me to be so sad. Lonely. Rather inglorious.

Alas, this was blindly naive, and not just because my high school mascot was a rebel (they’ve since changed it), but because the organization that erected Chip in 1899 was — deep sigh — the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who inscribed the monument with a clear message for anyone who cared to read it: “No country ever had truer sons, no cause nobler champions … In legend and lay, our heroes in gray shall ever live over again for us.”

This, as the The New York Times noted, is obviously painful — particularly for people “who felt the weight of slavery’s long shadow.” Also? Monuments like these give “a distorted impression” of even the Confederacy’s history, offers University of Pittsburgh professor Kirk Savage. Savage studies the history of art and architecture, and has written extensively about monuments and their role in our societal memory and identity; he also sits on the board for the great Philly-based Monument Lab. Throughout the South, Savage says, “there was far from unanimity about the Confederate cause.” You just wouldn’t know it from the monuments.

This is no doubt true in Franklin, which is perhaps best known historically as the site of an infamously bloody battle. (The Union won.) There’s a great deal of tourism built around historic homes from the era, plus battlefields, cemeteries and museums. Some residents would surely tell you that the Chip statue is a similar sliver of history preserved. But, to Savage’s point, given its sponsors (an organization that still owns the statue and the land beneath it) and the Jim Crow era timing of its debut, most sentient beings in 2023 understand this is not true in fact or in spirit. It’s a piece of history, sure (what isn’t?), but all alone up there, it has for 124 years repped a cause that was “on the wrong side of history and humanity,” to borrow from Landrieu.

“There’s a really fundamental question here about whether you can solve this problem by simply adding new and different monuments that represent other constituencies without changing anything, without having to reckon with the existing narrative out there in the commemorative landscape,” says Pitt’s Savage.

Given all of this, it was no great surprise when, in the aftermath of the violence in Charlottesville in 2017, petitions started floating around to have the statue taken down. It was also no great surprise that just as many people signed petitions to keep it up.

In any case, as with Marconi Plaza’s Columbus, significant legal hurdles were likely to make the journey toward moving the statue long and hard, if it could happen at all. Instead — or at least, in the meantime — a small group of residents mobilized to launch something they aptly called “the Fuller Story.”

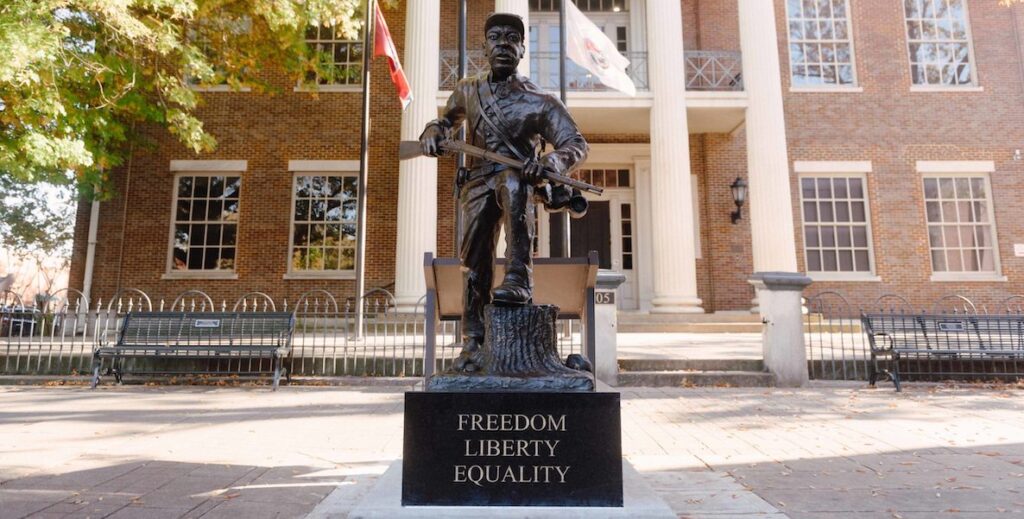

With city approval (“the most important thing we’ve ever done,” one city alderman told the Times), the Fuller Story group — led by a lifelong Franklin resident, a Black preacher who’d grown up under segregation — fundraised for, commissioned and erected a bronze statue of a Black Union soldier fighting with the U.S. Colored Troops, weapon in hand, broken shackles around his ankles.

The piece, called March to Freedom, honors the estimated 180,000 Black soldiers who fought for our country — again to Savage’s point, a piece of history just not often covered or represented in public spaces. Around the statue are five historical markers that address the selling of human beings, the lives and roles of Black soldiers who were fighting against the Confederacy, and the Reconstruction era for Black Americans.

On my trip home, I saw dozens of people gathering on the Square to stop and study it, to wander between the monuments. I did this myself with my eight-year-old son, surprised by the potency that existed just in the contrast between the two statues and the stories they told, that I then told to my son —and I was similarly moved by the crowds of people also talking about it. Of course, the statue was relatively new at that point, but now, more than a year on, one downtown business owner tells me, people are still stopping to look at March to Freedom, to read the plaques.

The Reckoning

So, okay then. Bochetto and Platt, I give. Why not two statues for Marconi Plaza?

If monuments help tell a story about who we are, and if — on a meta level — they make us think about who we honor and why, then two statues, created in different times, for different reasons, sitting as if in conversation with each other, can say a great deal. I saw it: Shame and rebuke and violence and misguidedness and bravery and sadness and resolve — a tiny slice of our history, in its old and ongoing complexity. Zoom further out, and it’s also the real-time evolution about who is telling stories, and how we try to counter and correct the narrative. Which is an admirable pursuit, in the end — especially if we do it well.

There are pitfalls to watch out for, yes. In Franklin, critics have rightly noted that March to Freedom isn’t as towering or as centrally located as the Confederate monument. It feels like what it is — added on. But then again? He stands roughly at eye level, which means you can study him. Touch him. And people do. And his location, poignantly, is just in front of the town’s historic courthouse — the spot where once they sold Black human beings as slaves.

Savage, for his part, brings up another issue. “There’s a really fundamental question here about whether you can solve this problem by simply adding new and different monuments that represent other constituencies without changing anything, without having to reckon with the existing narrative out there in the commemorative landscape,” he says. You might try to do that by supposedly balancing it out, but “I have difficulties with that because I think it’s a way for people to escape the ability to reckon with the harms created by these myths and these monuments.”

If monuments help tell a story about who we are, and if — on a meta level — they make us think about who we honor and why, then two statues, created in different times, for different reasons, sitting as if in conversation with each other, can say a great deal.

And if we don’t reckon with the harms? “We’re not grappling with our history in an honest way,” Savage says. Particularly because these figures we’re talking about aren’t neutral entities. Confederates, Columbus: What they stood for, and did, and ushered in continues to do harm.

But … what if, in some cases, reckoning with harms doesn’t always mean removal, but something else? Something that elevates public discourse? Not saying it’s easy. I do share Savage’s worries about the potential for “just put a statue on it!” blitheness, about the optics that might suggest that there’s some equal and opposite monument to neuter Columbus’ offenses.

The flip side of that, though, is the great potential in the process of getting to, yes, a fuller story, to see in Philadelphia as I did in Franklin the power of the contrast and conversation between two monuments. I’m talking about the gatherings wherein stakeholders listen to one another; the conversations about what part of the story might be better or more honestly told; the decisions about who gets to weigh in on the creation of a new monument, and why.

Isn’t that a way of reckoning? Can’t it be?

We have so many resources in this city for making meaningful, community-minded art in our public spaces: Monument Lab, Mural Arts Philadelphia, devoted Historical and Art commissions, and too many academics and artists and historians and activists to count. All storytellers, in their way, who could help round out part of this narrative. We have the stories, too. I read once about the unlikely survival of the Taíno people — an indigenous Caribbean tribe that was there when Columbus landed in 1492, and still exists, against the odds.

Can I picture walking my son between something like a new Taíno monument and the old one to Columbus, and talking about them both, the way I did in Franklin? I can. And I’d like to.

THE PHILADELPHIA CITIZEN ON HISTORY-MAKING PHILADELPHIANS