As our city is beginning its recovery from the pandemic, it has become more evident that Philadelphians of color, especially Black Philadelphians, were hit immensely hard. Financial losses, learning losses in our schools, the actual loss of life — have been devastating to the people who make up our city.

The pandemic unearthed health disparities, including access to care and who is left behind by our current health system. For example, the Economy League noted that as Black Philadelphians have higher rates of chronic diseases due to “decades of systemic poverty and racism, Black Philadelphians face a higher risk of developing severe cases of the Covid-19 virus.”

This is devastating news to those of us who have spent our years working to improve outcomes and change health disparities in Philadelphia. However, one health disparity has existed for decades that has not received enough attention.

There are also only four drugs currently available to treat sickle cell, even though less common diseases with predominantly White patients, such as cystic fibrosis, have as many as 15 available drugs.

The African American community has struggled with sickle cell anemia for far too long. There are about 3,000 adults with sickle cell in Philadelphia. In Pennsylvania, that number grows to 3,870 people with sickle cell.

I serve on the House Health Committee and am the subcommittee chair of health inequalities for the Pennsylvania Legislative Black Caucus. These roles give me the opportunity to see how sickle cell disease has drastically impacted communities of color.

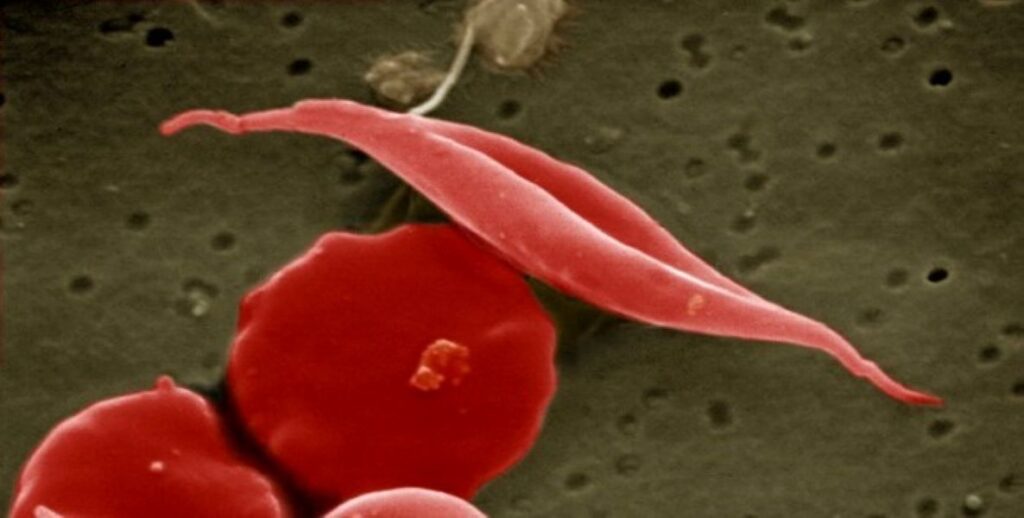

Sickle cell disease impacts more than 100,000 Americans. Approximately 2,000 babies in our country are born with sickle cell every year, the overwhelming majority being African American. Sickle cell disease can reduce life expectancy by up to 25 years and can cause stroke, anemia, chronic pain, and vital organ and tissue damage.

Given that most Americans living with sickle cell are African American, they also deal with the challenge of racial bias in our healthcare system.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) categorizes racism in healthcare as one of the primary causes of health inequities for African Americans. For sickle cell patients, this means they are misunderstood by healthcare providers who doubt the severity of their pain and question their motivations for requesting pain medication.

Sickle cell was discovered 100 years ago. Yet it has received much less research funding and pharmaceutical investment than rarer diseases with primarily White patient populations. There are also only four drugs currently available to treat sickle cell, even though less common diseases with predominantly White patients, such as cystic fibrosis, have as many as 15 available drugs.

On top of dealing with the disease itself, sickle cell patients face institutional barriers to accessing the few available drugs and treatments. Most sickle cell patients rely on Medicaid for health insurance. They often do not live long enough to reach Medicare eligibility, and the severe health complications that accompany a sickle cell diagnosis make it extremely challenging to gain employer-sponsored health insurance through a full-time job.

Currently, Medicaid coverage varies significantly by state, and considerable gaps in coverage across state lines create persistent inequalities in what treatments sickle cell patients can access.

Here in Pennsylvania, we have nonprofits doing outstanding work to connect patients with the resources they need. This includes helping patients navigate health care bureaucracy, providing emotional support, and educating them on treatment options. However, for all these fantastic organizations’ work to help sickle cell patients, they cannot cure sickle cell disease alone.

We need a coordinated federal solution to ensure that all patients can access every sickle cell treatment available. With potentially curative new therapies in the not-so-distant future, we have no time to waste here.

I am urging the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the Department of Health and Human Services to create a working group of sickle cell stakeholders to advise on policy changes and best practices to expand the accessibility of drugs and therapies. This group will be instrumental in ensuring Medicaid patients can access new treatments on day one of their FDA approval.

We have to think ahead as leaders in addressing our most significant health challenges, some of them ongoing for decades, if we want to be prepared for the next health crisis like Covid-19. The pandemic revealed that challenges within our current system would be exacerbated by any shake in the foundation. It is time we invest in the communities that need it the most.

State Representative Stephen Kinsey represents House District 201. He currently serves on the House Health Committee and the subcommittee chair of Health Inequities in the PA Legislative Black Caucus.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who stipulate to the best of their ability that it is fact-based and non-defamatory.