Megha Kulshreshtha, a graduate of Villanova, had been working in finance for a few years when she noticed how restaurants disposed of excess food on her walks home from the office. With hundreds of thousands of people across Philadelphia battling food insecurity, food that was both safe and edible wound up in the dumpster.

This bothered Kulshreshtha, whose parents immigrated to the U.S. from India and did not come from privilege or wealth.

“My parents came into this country with $20 in their pocket,” she told The Philadelphia Citizen in 2017. “My mom would always tell us about times when she’d thrown birthday parties for $20 because she’d figured out how to make that dollar stretch. Seeing the shops throw out fresh food just never really sat right with me.”

“The biggest barrier to change is really inertia,” Donovan says. “Everybody is well-intentioned, they want to do something good, but if there are barriers, if it’s a little too hard—that tends to run counter to getting those well-intentioned activities done.”

When The Citizen first covered Kulshreshtha, she was still a real estate investor running her nonprofit organization Food Connect from her laptop at home. But in the years since its 2014 launch, Food Connect has grown from a small volunteer force rescuing meals from a few restaurants a week to a food donation logistics service, connecting more than 100 food donors in Philadelphia to over 400 recipients in and around the city.

Partnering with health care networks, school districts, caterers, restaurants, and grocery stores, Food Connect delivers thousands of pounds of food once destined for landfills every month to vulnerable individuals and the hunger-relief organizations that serve them.

Creating a silent middleman

Most businesses have no desire or incentive to waste food and would prefer to donate what they cannot sell, but doing so is not that simple. Restaurants like Pret A Manger, which has four locations in Philadelphia, follow a “made today, gone today” model. Jorrie Bruffett, president of Pret A Manger USA, explains, “Our donation list contains only products where we can ensure quality and safety is up to our standards upon arrival.”

Safety is a major concern, which limits the amount of hot prepared food that a restaurant can donate because of temperature requirements. Knowing what organizations in the area need food donations, what they can accept, and when they can do so requires outreach and networking. City traffic, parking restrictions, and building restrictions further complicate matters.

“The best part of working with organizations such as Food Connect is how they streamline the donation process,” Bruffett says “Our team members know what they need to do to prepare for a Food Connect pickup. In turn, Food Connect handles the logistics to distribute our donations to those who need them most. We rely on the structure that Food Connect has in place to organize transportation, refrigeration and timeliness along with their network of local agencies to efficiently distribute donations to those in need.”

Kulshreshtha’s innovative idea was to do just that—to streamline the donation process, by providing a silent middleman to match excess food with those who needed it. She visited restaurants and shelters to organize a pickup and delivery routine. At first, she made most of the deliveries herself alongside several volunteers, getting calls from restaurants at the end of a shift, retrieving donations, and transporting them to a nearby aid organization.

A little help from the Pope

Several significant events in Philadelphia were catalysts for the growth and development of Food Connect. The 2015 visit from Pope Francis brought a tremendous number of visitors into the city but also generated unprecedented amounts of excess food.

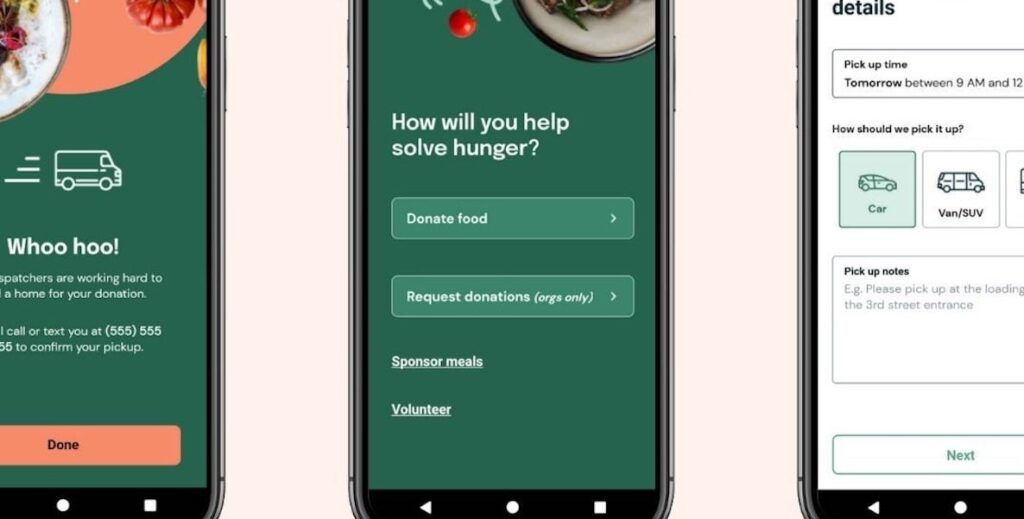

The Democratic National Convention in 2016 was bound to create food waste to the same extent that the pope’s visit had. Sankalp Kulshreshtha, Megha’s brother, worked with her to design an app that would allow donors to input what they had available and when, allowing Food Connect to pick up the donation and deliver it to the nearest shelter with a matching need. The app went live during the 2016 DNC in Philadelphia and demonstrated Food Connect’s ability to leverage technology for the benefit of hunger relief.

When Food Connect won Development Project of the Year at the 2016 Philly Geek Awards, they were facilitating the donation of 2,000 meals on average monthly. The April NFL Draft held in Philly the following year resulted in over 21,000 meals donated through the app.

Aurica Donovan is the community relations and program director for Food Connect. In the two years she has been on the team, she has witnessed its impressive growth and expansion of services. “The biggest barrier to change is really inertia,” she says. “Everybody is well-intentioned, they want to do something good, but if there are barriers, if it’s a little too hard—that tends to run counter to getting those well-intentioned activities done.”

The app works for any restaurant, retailer, caterer, or vendor that potentially produces excess food. While individuals can sign up to donate, perishable meals are only accepted from licensed vendors to ensure safety. In addition to canned and dry goods, individuals may choose to sponsor meals with a monetary donation.

“Access is about, Can I get this food when I don’t have a car?,” says Donovan. “That last-mile delivery has been a lifesaver.”

The donor provides details on what they have to donate and when it will be ready for pickup. Donations can be as small as five pounds. Organizations that serve the hungry have comprehensive profiles on the app, detailing their storage capacity, whether they can accept perishables and any specific product needs. This data allows Food Connect to match the donor and recipient typically within an hour.

Food Connect’s driver pool comprises volunteers, independent contractors, and other third-party vendors. “We kind of think of it as an aggregator, to find the best fit based on what the delivery need is,” explains Donovan. “It’s a match-making enterprise.”

The combined power of technology and data makes this operation possible, from the matching of donors to recipients to arranging timely pickups and deliveries through the driver pool.

Twin problems: Food insecurity and food waste

According to the United Nations’ 2021 Food Waste Index Report, more than 930 million tons of food go to waste every year. Most—61 percent—comes from households, but 26 percent originates from food service and 13 percent from retail markets. Americans waste more food than any other country. It is estimated that between 30 and 40 percent of the food supply in the U.S. goes to waste. More than anything else, food takes up the most space in U.S. landfills and accounts for 11 percent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Some food waste cannot be avoided, such as spoilage, which can occur anywhere between farms and retail due to problems in processing or transport that expose food to pests, mold and bacteria. Once the food arrives in stores and restaurants, the primary causes of waste become over-ordering and culling of “blemished” produce. Consumers continue this process by purchasing more than they intend to cook and misunderstanding expiration dates. How many of us have that weekly ritual where we toss out the vegetables we were going to use for that Pinterest recipe we forgot about?

RELATED: Want an at-home option to battle food waste? Compost!

Stripped of the raw emotion imbued in the word “hunger,” food insecurity is defined by the USDA as “a lack of consistent access to enough food to live an active and healthy lifestyle.” This definition helps clarify a complex issue for people in the United States: free from famine, war and ecological disaster, people go hungry because of poverty. In one of the wealthiest countries in the world, hunger doesn’t stem from a lack of food but a lack of access.

Covid-19’s impact on public health and the economy only worsened the problem. The USDA Economic Research Service report Household Food Security in the United States in 2020 shows that the 2019 food insecurity rate across all households was 10.5 percent prior to the pandemic. This rate was the lowest in over 20 years, yet still also represents 35 million people, including 11 million children.

Households in the U.S. with children experiencing food insecurity increased from 13.6 percent in 2019 to 14.8 percent in 2020. For Black households, that rate increased from 19.1 percent in 2019 to 21.7 percent in 2020. Feeding America, America’s largest hunger-relief organization, estimated that 42 million people in 2021, or 1 in 8, experienced food insecurity this year.

Philadelphia consistently maintains the highest poverty rate among the nation’s 10 most populous cities. As of 2021, poverty stands at around 23 percent. Feeding America’s 2019 numbers indicated that 14.4 percent of Philadelphians—226,890 people—suffered food insecurity. The Office of Homeless Services reports that in 2021, that percentage increased to 16.3 percent.

The “last mile delivery”

Food Connect is uniquely positioned to meet the challenges of providing aid during a public health crisis. “Within Philadelphia, the pandemic has been crazy, just like it is for everybody else, and with that, we’ve really expanded our focus on last-mile delivery,” says Donovan. “That’s getting meals directly to the doors of families and individuals that are truly food insecure.”

They did that by partnering with organizations like Caring for Friends to support and expand their work in the community.

This “last-mile delivery” concept is crucial for continuing food aid during the pandemic. Conditions limited the means to address hunger as many individuals could not risk traveling to food pantries and shelters to pick up food donations. Many organizations faced closures for public safety concerns and volunteer shortages. Getting food efficiently from a source to where it’s needed requires logistical expertise.

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) saw this need to provide for its most vulnerable patients, for whom nutrition is essential to recovery, substantially increase in April 2020. CHOP partnered with The Common Market and Food Connect to deliver produce boxes directly to patients’ homes. The USDA funded the project under its Farmers to Families program. The Common Market sourced food from local farms and sent it directly to CHOP families through Food Connect, which over 16 weeks was able to deliver 95,000 pounds of food.

“This is a really successful model because we each do what we’re best at, we each do the job that we’re skilled experts at, and then ultimately, you see the direct impact,” says Donovan of the campaign.

The future of hunger relief

Since 2020, many grant organizations and donors have been looking at hunger relief and social aid in general in a new light. Resources are directed to make hyperlocal impacts down to the zip code and focus on helping people access aid in their community. “That distribution piece has been really coming through, and for us as a logistics company, we’re like, finally!” Donovan says. “Access is about, Can I get this food when I don’t have a car? And with bus fare being what it is to get you to a site, there’s no guarantee that you will get that food when you make it there. That last-mile delivery has been a lifesaver.”

Food Connect has partnered in Philly with the Share Food Program, Philabundance, Fair Food Network, and Main Line Health. Their relationship with The Green Light Fund, a national organization that funds community initiatives in Philadelphia, brought Food Connect into San Francisco, another city where food insecurity has grown as gentrification has reduced the buying power of even middle-income earners.

“San Francisco and Philadelphia are always in the top hungriest cities in America. We are trying to meet that need where the need is,” Donovan says. As a launchpad, Philly is ideal, Donovan says: “What we do well in Philadelphia, we can replicate that in a place like the Bay Area.”

Donovan says Food Connect approaches expansion intentionally and with significant pre-planning. The first consideration is the level of need, measured by the national food insecurity average, versus the market, population, poverty, federal support, and SNAP threshold. Then they look at existing programs and hunger relief organizations, the level of commitment to hunger relief in the area, and available funding. The aim is to have partnerships or pilot programs in place before launching into any new market to ensure operations run smoothly.

In the last year, Food Connect has formed partnerships with various food distribution agencies in San Francisco, proof that their model works in any location where there is a need—which is to say, anywhere in America.

“We’ve been fortunate enough to build these trusted partnerships because really, at the end of the day, we’re not in competition,” says Donovan. “We’re in this to feed the hungry.”

RELATED