[Ed Note: An essay contest based on Jitish Kallat’s moving Philadelphia Museum of Art installation—a physical rendering of a letter Mohandas Gandhi wrote to Adolf Hitler in 1939—drew some 400 submissions from high schoolers around the region. Many were thoughtful and wise, well beyond their writers’ years. Erinda, a student from the Arts Academy at Benjamin Rush in the Northeast, was awarded $10,000 from the Pamela and Ajay Raju Foundation at a ceremony at the PMA last week. Below is her winning essay.]

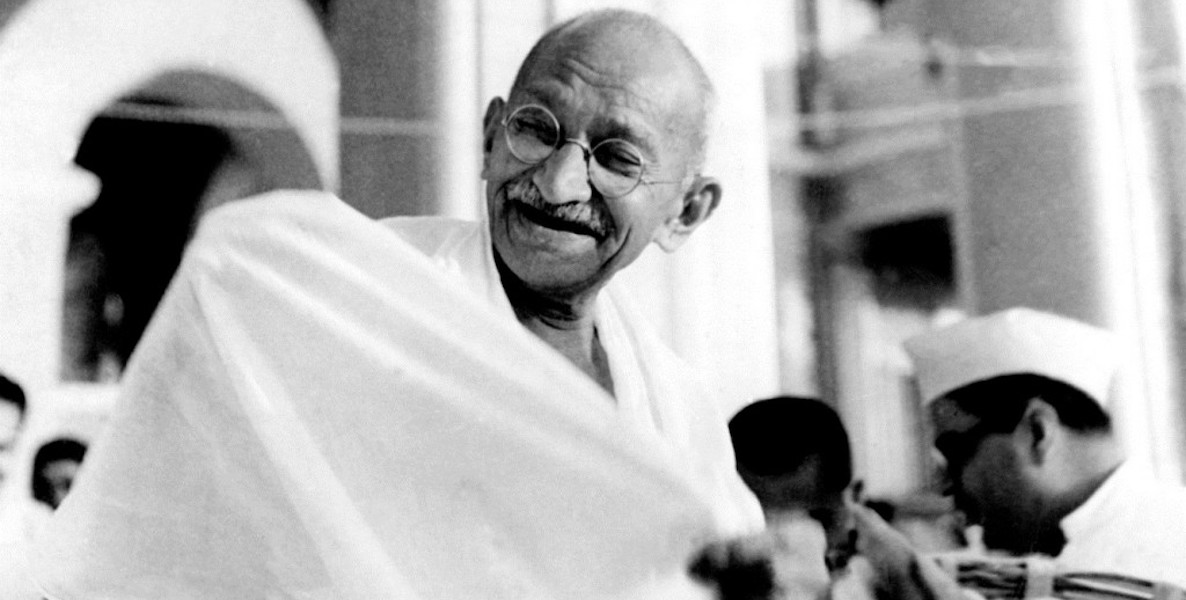

I don’t think Gandhi was some sort of phenomenal exception to a dejected civilization. On the graph of human compassion and decency, our history doesn’t track statically for the first thousand years, build up to a spike during Gandhi’s lifetime, and then trickle down again. I’m not trying to discredit him; I just don’t think that we should look at his actions as out of our league in terms of moral conduct. In fact, I think that’s something that he wanted people to understand: that he was leading by example and as a common man, that the ability to empathize and dissent peacefully is in all of us, if we choose to act on it.

If we choose to act on it. I can’t make people do things. But this is what I believe:

It comes down to hope. I’ll explain.

November 9th, 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency, and the sun didn’t shine. But it did rise, and the Earth did spin, and somehow that idea that the world wasn’t ending with his election was a source of some solace for me, yet I was still disappointed. I despaired in the fact that he was elected because I could not and will not tolerate his campaign of racism, islamophobia, misogyny, and bigotry. Sixty-two million people voted for him and implicitly accept everything he stands for, so I have to make my standing explicitly clear.

I wanted to gain some sense of location. November 9th threw me off my course of where I thought this country was headed. It sent me to a place that I knew existed, but as a young, white girl born with privilege, I have never been; I felt unsafe. I needed guidance, so I sought it wherever it was offered. This is what I found—brilliant people prepared to organize:

Colson Whitehead provided a simple, solid mantra: “Be kind to everyone, make art, fight the power.” A friend on my Facebook feed wrote that while “today we mourn, tomorrow we rise.” Hillary Clinton told 65,844,954 people to “never stop believing that fighting for what’s right is worth it.”

Hatred is not inbred, and human decency is not a supernatural ability. We hold prejudice and biases and animosity just as we hold compassion and empathy and kindness. I’m asking that you act on the side of decency through radical hope. It’s a difficult thing to do because it requires immense effort. All good things do.

Good advice, but I wasn’t there yet. I felt too broken to pick up all the pieces again and protest. I was still lost, still disoriented, until I found this:

“But all the fighting in the world will not help us if we do not also hope. Radical hope is not so much something you have but something you practice; it demands flexibility, openness, and what Lear describes as ‘imaginative excellence.’ Radical hope is our best weapon against despair, even when despair seems justifiable.” Junot Díaz’s radical hope. And just like that, I found my location: what I was going to consciously hold on to these next 4 years, 8 years, 12 years, and then some.

My English teacher Mr. Feldman is a tall, lanky man of considerable wisdom. I don’t think he’d mind me describing him in that way. One day, he asked me, “How do you argue with a guy as illogical as Donald Trump?” And I think about that question, and how I answered him that day, and I realize that the same question is being asked now—How do you communicate with someone you don’t agree with? How did Gandhi ever write to Hitler? How was it done peacefully?

You do it through Díaz’s hope. The active, conscious practice of actually listening to someone when they speak, looking at them as your equal, and keeping an open mind in spite of their ideas. Don’t get me wrong—this is not about tolerating intolerance. It’s about how you go about combating intolerance. Díaz said we can’t fight without hope. I think that’s because you can’t communicate with someone without understanding them first. I know sometimes the desire to scream the truth in frustration—“you’re a racist!”; “you’re encouraging discrimination!”—is overwhelming, but you can’t start a debate with an indictment. How often does a racist accept the accusation that they’re a racist? Never. So what if you started the debate without the primary objective being to criminalize?

This is where I come back to the statement I made earlier. If we choose to act on it. It’s a choice, because hatred is not inbred, and human decency is not a supernatural ability. We hold prejudice and biases and animosity just as we hold compassion and empathy and kindness. I’m asking that you act on the side of decency through radical hope. It’s a difficult thing to do because it requires immense effort. All good things do. That effort is worthwhile, and to assure you of it, I leave you with a quote by the philosopher who inspired Díaz, who inspired me:

“What makes this hope radical,” Lear writes, “is that it is directed toward a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is.”

Radical hope is rooted in the belief that if it is practiced, it moves toward a world that is better than the one we find ourselves currently debating in. Gandhi knew this when he started his letter with “Dear Friend.” Can the same be said about arguing to divide, to accuse?

To answer your question: There is absolutely hope for seeking common ground with our opponents that not only appeals to our shared humanity, but secures the continuation of our shared humanity.