Stepping into Puttyworld, the Norristown-based flagship of Crazy Aaron’s Thinking Putty, is like walking into every 9-year-old’s dreamscape.

Set against white walls in the sun-filled space, on the first floor of the former mill that also houses Crazy Aaron’s offices and production spaces, are racks and racks of the company’s signature silver tins full of more than 100 types of putty and accessories, all available to try-before-you-buy.

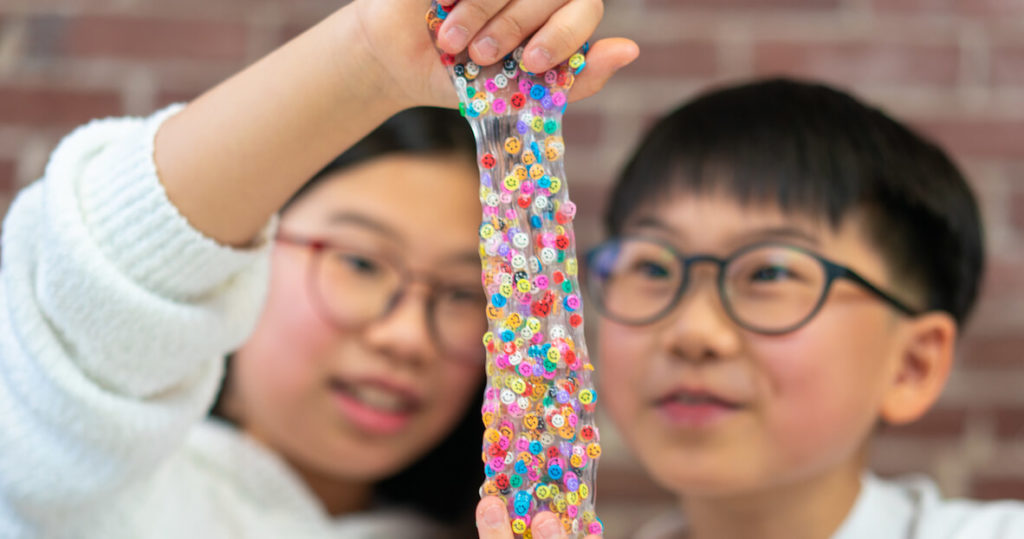

If you are, or know, a parent or a child, you have most definitely come in contact with Thinking Putty: Not quite slime, decidedly not Play-Doh, Crazy Aaron’s Thinking Putty, the brainchild of Havertown native Aaron Muderick, is a line of malleable, silicone-based goo, akin to rubbery wads of chewed gum, in a good way—in a way that is, as countless YouTubers approvingly declare, in influencer shorthand, so “satisfying.” You can shape it and stretch it and mold it, without it ever drying out, like clay, or ruining your clothes, like slime.

Since the company’s official launch more than 20 years ago, Crazy Aaron’s has become the gold standard in the world of putty, a star in the ever-growing sector of “manipulatives”—toys like fidget spinners and pop-its, handheld items that simply feel good to play with. You’ll find Crazy Aaron’s at the twee, curated toy shop in your neighborhood, yes, but also at Target; it’s sold in thousands of stores in the U.S. and around the world—from Peru to South Africa, India to Ireland. In the U.S., a small tin of Putty retails for $3; a mega-tin is $50; the popular medium-sized tins are $15. While the company, privately held, doesn’t share sales figures, a CBS Sunday Morning segment from 2017 reported that it’s a multimillion dollar business.

Thinking Putty has proven to be more than a fleeting trend, the next slap bracelet or Beanie Baby, a fact Muderick attributes, in part, to social media. “Social media has played an important role because it allows children to set a way of thinking or an ideological box that is not defined by the outside world,” he says.

It’s also a business that’s dedicated to doing good. Muderick, who grew up watching his parents volunteer, has been committed not only to delighting customers with the product, but to positively impacting the community. In pre-Covid days, he’d run workshops with youth programs like Scouts and at The Franklin Institute and Please Touch Museum; throughout the pandemic, his team has been donating science kits to the students at FirstHand, the STEM program run by the Science Center, to reach West Philadelphia middle and high school students.

And he’s always been committed to offering work opportunities to people with intellectual disabilities. Prior to the pandemic, there were about 700 differently-abled people working for the company at offsite locations, in addition to many working on-site in Norristown, often with one-on-one support; post-pandemic, that number is 300, and climbing back up. “It is a rebuilding year for sure,” Muderick says.

The product and the ethos underlying it have enabled Thinking Putty to be more than a fleeting trend, the next slap bracelet or Beanie Baby. That’s a fact Muderick also attributes, in part, to social media.

“Social media has played an important role because it allows children to set a way of thinking or an ideological box that is not defined by the outside world,” he says. Kids today are making and consuming hours of YouTube videos about toys they love, toys they make, toys they repurpose and reinvent. Back when today’s adults were growing up, the big toy companies marketed their wares through paid commercials: Barbie Dream Houses and LiteBrites and He-Man figurines plugged at breaks during DuckTales and The Smurfs.

Thanks to social media, however, today’s kids don’t require, or even really trust, a go-between. “They don’t need a priest as an intercessor on the way to heaven,” Muderick says. “They can just speak what they feel, and kids are now the ones driving what the manufacturers want to make or do.”

Just another ’80s kid

There was a time when Muderick, ahead of the zeitgeist and now a bona-fide rock star in the toy biz, was less an OG and considered merely, as his brand implies, “crazy.”

“I was an ‘80s kid, and from the time I was very young, I was very into computers,” Muderick says by Zoom one late-summer day. “But by the time I graduated from college and got an actual computer job sitting at a desk, I was very fidgety.” There were two reasons for that, he says, looking back. “One was the sitting still part, and the other was maybe for the first time realizing that I wanted to do what I wanted all the time, not necessarily take an assignment and embrace it and do it, like you do when you work for somebody.”

He started amassing toys, little tsotchkes, around his desk. As co-workers would casually pilfer his store-bought putty, he started to wonder if he could make some himself, at home, as a sort of DIY side hustle.

He could.

And he did, selling it from his desk at work, and out of the trunk of his car at craft shows. “It seemed to make people happy, and I liked making people happy. And making it involved a lot of moving, which helped me with my fidgeting,” he says. But a few years into his amateur putty-making, the owner of the company he was working for called him to a meeting. “It’s us or the putty, Aaron,” he said. Muderick chose the putty.

Then living in Narberth, Muderick bootstrapped the small company on his own, growing from Narberth to Phoenixville and, in 2018, to the 100,000-square-foot HQ on Main Street in Norristown.

“It seemed to make people happy, and I liked making people happy. And making it involved a lot of moving which helped me with my fidgeting,” he says. But a few years into his amateur putty-making, the owner of the company he was working for called him to a meeting. “It’s us or the putty, Aaron,” he said. Muderick chose the putty.

As for the company’s commitment to hiring people with different abilities? Well, early into starting the company, Muderick recalled working as a teen at a factory that produced pet tags, and that the most upbeat and committed colleagues he’d met were those who happened to be differently-abled.

“There were a number of individuals with intellectual disabilities who worked there, and they were the happiest of all the employees. Psychologically, you talk about ‘flow state,’ being in your zone when you are just below your limit and really challenged. And depending on your personality and your skills, that comes at different levels for different people,” Muderick says. “For some people, putting things in boxes all day will make them lose their minds from boredom; for others, it keys into certain characteristics that make it very rewarding to do that again and again. I wanted to be working with people who wanted to be here, and who were as excited as I was. And that ended up being individuals from within the differently-abled community.”

Crazy Aaron’s has worked with citizens from programs through Catholic Social Services, Devereaux, Handi-Crafters, and more.

“We love Aaron and Crazy Aaron’s. They’re tremendous partners,” says Rich Bevan, president of Baker Industries, the nonprofit workforce development program that, for 41 years, has been serving vulnerable adults in the Philly area, connecting them to work experiences and training and education: adults with disabilities, adults on parole or probation, adults who are in recovery, adults who are homeless. “A number of our partners are folks looking to outsource work and although they’re very good customers, they’re not particularly aligned with our mission—we’re a supplier to them. But Crazy Aaron’s is very different. They’re very socially motivated, and they very much are committed to helping us fulfill our mission. It’s important to them that we’re serving the folks we’re serving, it’s not just a business relationship.”

The proverbial pivot

Covid-19, however, put a pause on those relationships. Early in the pandemic, the company had to shut down production operations for three months, per order of the governor. Muderick had to lay off much of his 80-plus-person full-time staff, including his employees with disabilities.

When the pandemic first hit the U.S., Crazy Aaron’s began producing hand sanitizer, in partnership with nearby Five Saints Distilling, and was able to rehire some employees. But even as pandemic restrictions eased, many employees with disabilities weren’t able to make it back to work—due to commuting hurdles and fears of the virus, and the lifestyle changes and challenges we’re all facing. Recently, however, the company brought on a new staffing agency that focuses on vulnerable populations and provides transportation to the Crazy Aaron’s facility.

MORE LOCAL BUSINESSES DOING GOOD

- Kári Skin in Old City is taking the “mean girl” out of the beauty industry

- Home Appétit offers delicious, healthy meal deliveries with a do-good twist

- Simply Good Jars is seeing all kinds of green after a star turn on Shark Tank

- Truth & Consequences finds big success by taking really good care of employees

Just as the pandemic affected Crazy Aaron’s workforce, so, too, has it impacted sales. Muderick says that within the toy industry, sales were up during the pandemic, but not consistently across categories. “If you were arts and crafts, you were up 200 percent; versus if you were plush, you were probably down 75 percent. For us, it was absolutely a [negative] hit,” he says. “We’re an impulsive product, we rely on people shopping in stores and seeing a pretty thing they didn’t know existed and going Ooooh, what is that, I want to touch it, I want to feel it. And so the pandemic was not great for our product line.”

Even though conceptually, he says, it would be perfect at this time: Just think about how we’ve all increased our restless, nervous habits—nail-biting and teeth-grinding and doomscrolling … and worse. “Our core customer base carried us through because they knew they needed a new Thinking Putty to make it through, say, Zoom-school, but as for the rest of the world, they weren’t stopping at a Cracker Barrel during the pandemic and saying Oh what’s this cool little tzotchke, I’m gonna buy it and give it a shot.”

Too bad, too. Because whether you’re gnawing at your own gums or picking at your own skin, suffering from insomnia or resuming an old smoking habit, picking up a tin of Putty helps. You feel distracted, you feel better. You can’t not.

Looking up

Things at Crazy Aaron’s are starting to look up. For one, Puttyworld re-opened, after having closed for several months in 2020. The company is on a hiring spree. With the new hiring agency, Muderick anticipates headcount going over 100 before the end of the year.

And a bunch of cool new products—“Hide Inside” putty with hidden emoji pieces embedded within it, glittery green “Dino Scales” putty, to name a few—just hit the market the first week of September.

“For some people, putting things in boxes all day will make them lose their minds from boredom; for others, it keys into certain characteristics that make it very rewarding to do that again and again,” Muderick says. “I wanted to be working with people who wanted to be here, and who were as excited as I was.

Of course, Muderick is right about that in-person appeal, the power of the impulse purchase. On a recent Tuesday morning, I headed to the Norristown headquarters with the intention to size up the place in-person, give this article some color. Instead, after a cheery salesperson demo’d the latest iterations of putty for me, I left with 12 tins of product in different sizes and colors—treats for my children, for our sweet new neighbors’ kids, some to stash away for Tooth Fairy prizes and upcoming birthday parties. Products with names like “Sasquatch Poo” and “Cryptocurrency,” even “The Amazing Prediction Putty,” which pays homage to the classic 8 Ball toy: Ask it a question, then mush and mash it til an answer rises to the top.

Setting aside that particular tin as my own, an outlet to get me through meetings and calls and self-indulgent writer’s block, I say out loud to no one: Wouldn’t the world be a better place if we all had some putty at our disposal?

An answer rises to the surface: For sure.

Could putty solve the world’s problems? Of course not, I know. But I also know that, heading into Crazy Aaron’s HQ, I was feeling shitty about the state of, well, everything: education, vaccinations, environmental decimation. And when I left, for at least just a little while after, I felt hopeful, youthful, joyful.

My inner nine-year-old had been released and, as the kids on social media these days might fondly say, found the whole experience so…satisfying.

RELATED