It’s 6:35 am, and Chef Deborah Anthony has already arrived at St. James School to begin preparation for lunch. Because I’m five minutes late, I stand outside the iron gates calling the switchboard, and looking across the street toward the tiny stone chapel hunkering next to the graveyard. Classrooms and lunchroom have been carved into the parish house. Lights are on. I see grown-ups inside.

Indoors, at 6:40, teachers are preparing, too: reading, copying worksheets, putting notes onto computers connected to SMART boards. The furious preparation everywhere reminds me of St. Paul’s, the New Hampshire boarding school where I studied and later taught, where the children and their accomplishment mattered so much that we adults thought of them constantly. Every morning we awoke to solve the problems that kept them from learning. The whole child: that’s whom we were to attend, mind and heart, body and soul. My friend from college taught at St. James. She found me and took me to meet the new science teacher, a young black man. He can’t talk long, because he’s still preparing for the day.

Downstairs, past the art room and a coat closet and restrooms is an open lunch room, also used for afterschool and small-group meetings. Inspirational signs hang on the wall, and the names, in Latin, of internal groups. Not quite Hogwarts. More American, browner, with Martin King’s photo on one of the posters, but there’s magic here, too, and the unspoken understanding that evil lurks abroad, that not everyone wishes these children well, although here they are safe.

In the kitchen, Chef Anthony fills out a form with the 7 am fridge-and-freezer- temperature check. She slips the paper into a clear plastic sleeve on the tall chrome door and welcomes me. At 7 am, Deborah Anthony looks sharp with dark wavy curls framing an open forehead and sparkling eyes. She is reserved at first, speaking courteously, her smile outlined by a plumberry lipstick. The radio up on a shelf throws out a light R&B buzz and bits of chatter from the Steve Harvey Show.

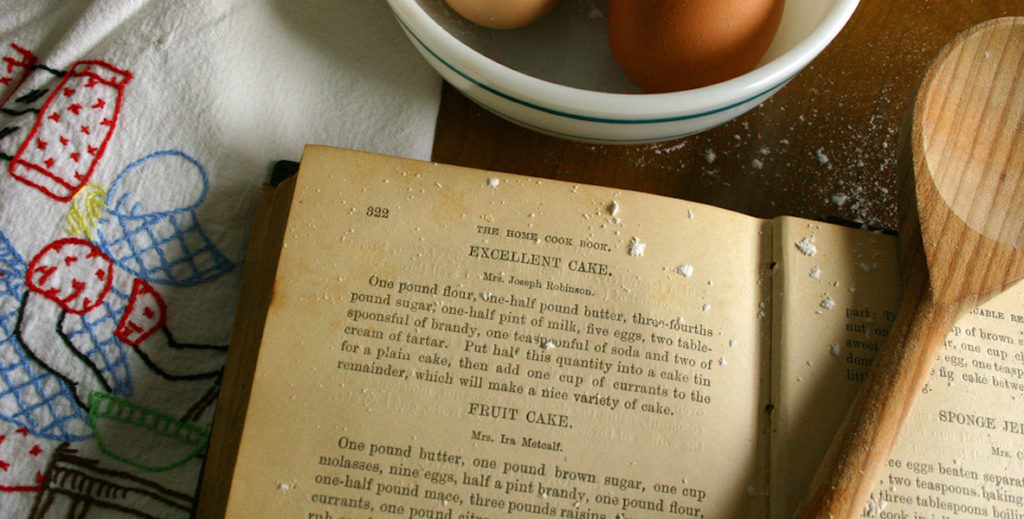

Anthony’s grandmother cooked superbly; she wrote her own cookbook, all her own recipes, but it got lost after her death at 96. Anthony’s mother was also a very good cook and a licensed hair designer. Anthony still remembers her mother “every Sunday in high heels and pencil skirts. She’d cook dinner before church and do hair. I was three. Remember Marcel curling irons?”

We whoop at the memory of mothers wielding hot hair-curling tools, and Anthony’s deep dimples flash. Hair design was Anthony’s first career choice, and her son works in a unisex salon. He even has a signature “man-weave” for balding men. She meant to go to him yesterday to have her own hair restyled, but there’ve been too many things…

That is the miracle of cooking in school and its challenge: that, like the rest of their education, staff must do an excellent job everyday, despite transit strikes and urban foxes, and I-don’t-want-to, and a hundred different palates.

Two deboned turkeys simmer in a vegetable broth on the back of the stove. Anthony prefers boiling rather than roasting because it keeps the meat moist and tender. They will take about two-and-a-half hours. On the table is a mixing bowl larger than a laundry basket full of frozen string beans and three gallon-sized cans of cannellini.

Anthony looks a few times at the menu plan suggested by the Vetri Community School program, a partnership with restaurateur and chef Marc Vetri, with whom she worked at the end of her 15 years at the elementary to high school boarding school, Girard College, where she made three meals a day for 800 children; proms; and catering for the president. St. James feeds not quite 100 middle-schoolers, teachers, and staff each day. Then, there are the St. James alums who return for homework and company, and Saturday staff meetings.

“At Girard, I’d be the head chef for Vetri in the summers. They kept asking me to open a school for them,” she says. “When I got here [to St. James] there was no kitchen, and I almost lost my mind! But I prayed on it, and talked to my kids. And I thought: God doesn’t make mistakes.”

The compact kitchen in St. James’ basement was renovated a few years ago at a cost of $200,000. DiBruno Brothers was the main sponsor, raising $75,000 for their 75th anniversary.

Once a working kitchen was installed, St. James could let go the standard boxed meals they were buying from the a school lunch service. Vetri’s Eatiquette program guides schools toward homemade lunches, using fresh foods, cooked from scratch each day, and served family-style at tables of 8 to 10. Today’s menu will be: pulled turkey on whole-wheat rolls, homemade barbeque sauce, Tuscan cannellini, green beans, and for dessert, grapes. Chef’s also prepping a meal that will be ready for the faculty’s Saturday meeting, while also thawing ground meat for tomorrow’s lunch.

Chef Anthony points to the mountain of red peppers she’s diced and the hill of chopped parsley alongside. Lemons next to it make a still life that she regards with workaday pleasure before grating lemon rind into the string beans and squeezing fresh lemon juice into them. We talk about bad knees and aching joints as she hoists the small bathtub of flavored beans onto great flat cookie sheets and slides them into an oven to roast at 425 degrees.

“I have a passion. If you don’t have a strong passion nobody’s going to get anything out of it.” Chef Anthony spreads her hand over the tray of whole wheat bun bottoms, ready for pulled turkey. Then she turns down the volume on the flashing eyes and dimples. “And a little tenderness.”

In the lunchroom, just outside the kitchen door, high children’s voices are practicing for All Saints Day: “Holy, holy, holy/Lord God almighty,/Early in the morning my song shall rise to thee…”

Jeremy Minsky, the food manager who started two days ago, is on his own, dashing, noticing, casting his eyes back and forth. The outgoing food manager has called in sick. Jeremy is filling brown bags with packets of cold cereal, yogurt, milk, and an apple and handing them to children who tumble down the steps, when Chef calls to him that she only has 48 buns. “I need you to check in the back or the other freezer, because other than that I’m going to need about 50 more.” She’s chopping tomatoes to go into the Tuscan beans; a flavorful steam comes from the green beans in the oven.

Minsky goes out one door, and from the corner next to the fridge out pops Joanne Behm, Associate Director of Advancement and executive Assistant to the Head of School. She goes into the back room, past white coats and jars of food to a closet stash of stationery supplies. Now that the school day is beginning, the kitchen feels like the set of a play, a comedy, where people pop in, say things or ask or bring or take, and then disappear. Behm, in addition to her work in development, has taken charge of the 10 chickens that live in a coop next to the basketball court. She stops to sniff the steamy air and to tell us that everyone can smell it upstairs. She also compliments yesterday’s soup: cream of potato, which her students, some picky, tried and liked.

Chef thinks she saw the fox this morning, and describes its long, low body, with the great tail dragging behind.

Jeremy Minsky comes in with rolls from a far-flung freezer; he looks relieved. Chef tells him that if he’d had to go buy them, he’d have needed to find somewhere that sold whole grain, not just wheat. “Same for pasta: whole wheat pasta; and when it’s rice, brown rice.”

Minsky nods. He’s taking it in, the whole whole-grain, whole-food, whole-child low-cal, high taste, micronutrient deal; he’s got a shopping list to check, too, and Chef reminds him that he’ll need to mark down not just the main ingredients from the Vetri list, but also the flavorings, herbs, and spices. So tomorrow he won’t have to run out, like he’s going to have to run out soon for chili powder and honey.

By 8:45 it’s warm in the kitchen, and Chef Anthony promises me that it’s going to get hotter. She makes us a pot of coffee, using regular Maxwell House coffee, but re-grinding it and adding cinnamon to make it fresher. For breakfast, then, I drink coffee and eat two coffee-cups full of string beans: a little heat, garlic, roasted, a pop of freshness from the lemon. I am surprised by the complexity of flavor and relative absence of salt. I smell the barbeque sauce as she pours in molasses. Parmesan into the cannellini.

Despite my depredations, after all the string beans are measured into bowls, weighed, covered with saran, and placed in the warmer, Chef Anthony has one bowl left over. That will be for the seventh-graders and an alumni group, kids who return to Kevin Todd and Becca Solnit, Director of High School Placement, from their high schools to the home that is St. James. The cannellini, four cans, not two, plus amended other ingredients, measure out perfectly.

“Shut the front door!” Chef Anthony scrapes every bean out of the giant bowl and we do a happy dance.

Someone on the radio is talking about paying child support. A few more teachers bounce in and out. Jeremy Minsky brings in the chili powder and honey. Chef Anthony grins as she pours it into the sauce and takes out the mixer. Done. Everything’s cooked. It’s another day when the food is ready for the children: on time, delicious, fresh, clean, low-cal, low-cost, high flavor.

Assistant to the Chef Sean Brooks comes in at 10, bringing his own quiet energy, a smile, shy at first, tying his apron. He attacks pots large enough to bathe toddlers and then attends to a tiny hillside of unwashed grapes. Brooks has just begun this year, and is learning not just the Vetri program, but how its principles work in this particular school, every day. That is the miracle of cooking in school and its challenge: that, like the rest of their education, staff must do an excellent job everyday, despite transit strikes and urban foxes, and I-don’t-want-to, and a hundred different palates.

With the barbeque sauce adjusted, Chef Anthony begins to pull the turkey. She drops a few moist shreds into my hand and gives me a plastic teaspoon of barbeque sauce. For sweetening, the recipe only calls for molasses, but she’s added a touch of honey, too.

“Tastes like somebody cares about me,” I say.

“I have a passion. If you don’t have a strong passion nobody’s going to get anything out of it.” Chef Anthony spreads her hand over the tray of whole wheat bun bottoms, ready for pulled turkey. Then she turns down the volume on the flashing eyes and dimples. “And a little tenderness.”

Lorene Cary, founder of SafeKidsStories.com, is a writer and lecturer at Penn. This is one in a series of articles that will run on The Citizen and SafeKidsStories.