One reaction to the recent news that the Sixers and developer David Adelman (full disclosure: a Citizen board member) are proposing a $1.3 billion arena at 10th and Market streets might be: Wow. That’s interesting. This could be a big bet on the future of the city. Now, how do we make sure it’s done right, so as to help spread prosperity, rather than further income and wealth divides?

That’s one way to greet the news. Another would be Councilwoman Helen Gym’s reaction. Within hours, she tweeted: “Today’s reminder: Billionaires don’t need public subsidies.”

You see the difference? The first is a constructive perspective that recognizes we all have to do our part to align growth with the common good — a perpetual struggle in cities. The second is about scoring cheap political points by vilifying rich folk who may just be doing something that could inure to the city’s benefit. Given that Sixers ownership and Adelman explicitly said yesterday they weren’t seeking city dollars for the project, Gym’s reaction seems to be knee-jerk ideology at its core.

The days of “If you build it, they will come” are behind us. If you’re serious about doing good while doing well you have to start thinking about new ways to advance a “we’re all in this together” sense of community in our public life.

So let’s try the more open-minded approach. Of course a new arena would benefit Sixers ownership. But would it also be good for the city? Would it spur inclusive growth, or hinder it? There’s ample evidence that, in a city long mired in subpar job growth, it could be a broad-based economic game changer — if done right.

Let’s back up for a minute

Before we get to the evidence, let’s back up and run through some context. The Sixers are seeking to move in 2031, when their lease at the Wells Fargo Center is up, not because that building itself is somehow antiquated. No, it’s mostly because they’re a tenant in someone else’s building, meaning they don’t get to keep all of their luxury seating revenue, which, along with ever-expanding broadcast fees, has become the name of the game in pro sports franchise growth. After all, the legendary Spectrum — RIP — had to go because it only had 12 luxury boxes, compared to some 80 at Wells Fargo.

Speaking of my beloved Spectrum, it bears harkening back to it. Going to a Sixers game or an Electric Factory-produced concert back then was a communitarian act — a diverse city would come together for a shared experience. At halftime of Sixers games, everyone — a working stiff taking his kids to a game, as well as real estate developer Steve Solms, the high visibility courtside crier — would have to navigate that narrow, smoke-filled concourse out by the concession stands. We all entered through the same doors and we all high-fived one another in reaction to the latest Dr. J aerial assault. We were all at the same game.

Today, as is so often the case in our stratified economy, there are different experiences offered based on your ability to pay. I’m a former Sixers season-ticket holder who still goes to a handful of games a year, always sitting near the action, not far from where the team’s ownership and Adelman cheer on the players. For them, like me when I attend, there’s parking, a private entrance and a dining club.

That working stiff who wants to take his kids to a game? He’s either relegated to the nosebleed seats, or damn near has to take out a second mortgage to afford lower bowl seats. When Pat Croce was a part owner and president of the Sixers, he’d greet fans streaming into the arena when the doors opened, and he’d pick out a select few who were headed upstairs and treat them to an upgrade to prime seats near the floor.

It was his way to at least mitigate against the trend, admittedly in isolated cases. But here’s why this is important: Historically, the miracle of the American city is its promise of shared experiences across class, race, and generational lines. In so many ways, we’ve gotten away from the notion of shared public life.

Now, the Sixers need to make the numbers work, so it’s unlikely that the cost of lower bowl seats in the new arena will come down. But there are ways that this new arena can represent a return to the days when citizens coming together for sporting events not only served middle class interests, but also helped create pathways to middle class lifestyles.

Here, then, a playbook for how this investment can drive smart inclusive growth:

Remember Jane Jacobs.

If you remember nothing else from the legendary citizen activist and author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it’s that cities are all about “feet on the street.” Vibrancy not only enhances public safety — it spreads opportunity. Bars, restaurants, shops, public transit and even parks fuel commercial interactions, yes, but also interpersonal ones. They’re lessons in how to live together.

That’s why locating sports arenas in the urban core has become something of a trend. It’s true that most surveys show that public subsidies for stadiums often lack a return on taxpayer investment. But the exceptions have occurred when they are located in center cities, spurring growth, as outlined by Wharton’s Ken Shropshire, author of The Sports Franchise Game: Cities in Pursuit of Sports Franchises, Events, Stadiums, and Arenas.

Shropshire was recently named Senior Advisor to the Dean for Wharton’s new Coalition for Equity and Opportunity; before his return to Philly, he ran Arizona State University’s Global Sport Institute. A few years back, he weighed in for The Citizen on Temple University’s negotiations with its neighbors to develop an on-campus football facility. “Newly-built stadiums don’t have to be exploitative entities,” he wrote. “They can work with the community to smartly manage growth.”

Shropshire provides a travelogue of intentional, equity-driven sports arena development projects that have qualified as win/win projects. Nearly 30 years ago, for example, Denver’s Coors Field opened in a blighted neighborhood. In short order, it jump-started a turnaround. As more and more bars and restaurants opened nearby, and more and more citizens walked the nearby streets, the city tripled its sales tax revenue thanks to the new stadium, fueling public investment in once-marginalized communities. You’d think that Gym and her fellow progressives would be all for expanding the tax base in that way, no?

More recently, the NBA’s Detroit Pistons helped fuel an urban renaissance in that city by moving downtown. A majority of those working on the new stadium’s construction were hired from its surrounding community, and the team shelled out $2.5 million to repair 60 of the city’s dilapidated basketball courts. The team, in partnership with the Detroit Employment Solutions Corp, provided job-training to those living nearby.

In Atlanta, when the NFL’s Falcons unveiled their state-of-the-art Mercedes-Benz Stadium, they also launched Westside Works, a nonprofit workforce development center created to ensure that the Westside neighborhood that flanks the stadium benefits from it. In addition to job training, there’s a new financial center to improve banking access and financial literacy, a new community center and youth leadership program, and increased law enforcement presence. In the stadium itself, local workers man the concession stands.

Double Down on the Power of Shared Space.

Too often, sports arenas look like foreboding fortresses and seem to say, in effect, to their neighbors: This is not for you. They conjure the prospect of gentrification and displacement just in their look. But there’s an opportunity to see sports arenas as public assets — and to design them accordingly.

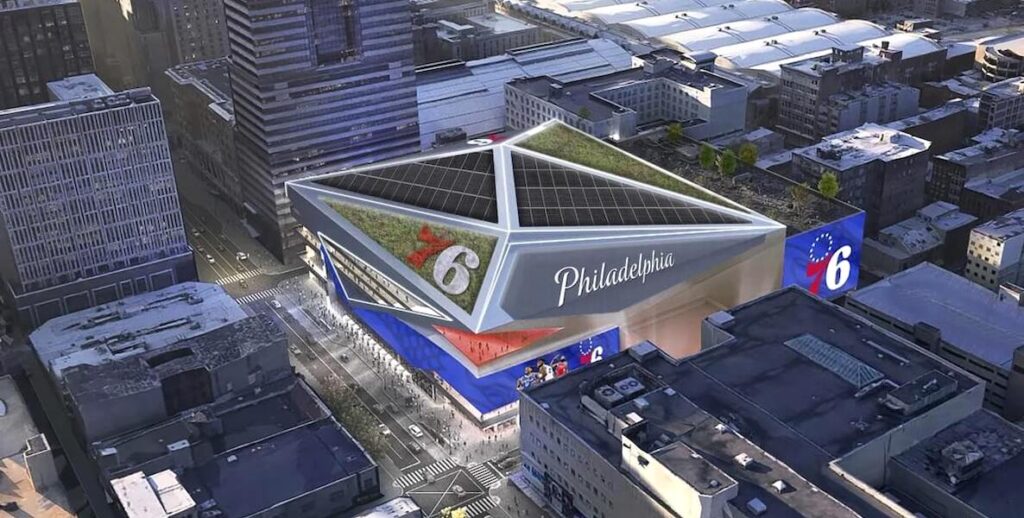

Adelman and fellow developer, minority-owned Mosaic Development Partners — whose founding partner Greg Reaves wowed us at one of our Development … For Good events — have hired cutting-edge San Francisco designer Gensler to conceive of the Sixers’ new digs. Gensler gets that this isn’t just about erecting a place for a bunch of highly-paid athletes to run around.

“Sports unify us,” Gensler writes on its website. “Like music, they bring people together across demographic and political lines to share in the grand spectacle of what humanity can accomplish. But with technology making it easier than ever before to watch the game virtually (or multiple games at once), we have to ask a question: What is the sports venue’s purpose? The answer revolves around one word: community. At every scale, these venues are becoming connectors whose scope transcends the sport itself. They’re doing it by focusing on what brings people and neighborhoods together for engaging, in-person, and memorable experiences.”

That’s why Gensler’s stadium for Austin FC — a Major League Soccer franchise in Austin, Texas — is open to community use on non-game days. There are youth soccer leagues, farmers’ markets and art shows. We’re not just a pro sports franchise, the building, in effect, says; we’re a staple of this community. It’s taking a page from Arizona State University, where Shropshire was helpful in transforming the 60-year-old Sun Devil Stadium into a year-round type of community center that also happens to host football games. They called it ASU 365 Community Union because it represents a hotbed of activity 365 days a year, with concerts, seminars, and street bazaars connecting campus and community.

“Newly-built stadiums don’t have to be exploitative entities,” Ken Shropshire wrote. “They can work with the community to smartly manage growth.”

It’s reminiscent of the strategy Earvin “Magic” Johnson employed in building his empire of inner-city movie theaters, as I chronicled in a long-ago New York Times Magazine story. It wasn’t about the movies. It was about using the theaters as safe spaces for communal gatherings. First, Johnson met with the leaders of the Crips and Bloods, and got them to agree to a cease-fire when on his property. Then he turned his spaces into de facto community centers, which included a first-of-its-kind partnership with Howard Schultz and Starbucks. On any given night, you’d see inner city residents sipping coffee, getting their blood pressure checked, or listening to live music.

The point is, the days of “If you build it, they will come” are behind us. If you’re serious about doing good while doing well — and I happen to know that Adelman is — you have to start thinking about new ways to advance a “we’re all in this together” sense of community in our public life. (Adelman did just that, actually, when he raised some $9.5 million for the The Horwitz-Wasserman Holocaust Memorial Plaza.)

There’s a whole architecture for social good movement, represented most dynamically by Boston’s MASS Design Group, which is reimagining public spaces in everyday life. It’s a nonprofit that cut its teeth revamping, from a design perspective, the very idea of what a hospital is in Africa — and it’s that kind of creative rethinking Philly can now embark upon when it comes to one of our singular passions.

I was pretty much the lone voice of outrage when the Sixers up and moved their headquarters to Camden a few years ago, taking 250 jobs across the river and costing the city a few million in lost wage tax revenue, after they’d gotten all sorts of tax breaks from Jersey. It wasn’t a travesty like Walter O’Malley’s slinking the Dodgers away from Brooklyn for better parking, but it was a painful reminder that this team so many of us feel is ours … really isn’t.

Over the past few years, there have been numerous reports that many of the companies lured by Camden haven’t hired locally, which has continued to stir outrage. I’d be surprised if the Sixers bring their jobs back to the Philly tax base (though a tough mayor and City Council would put it on the table), but there’s no doubt that, by now betting on Philly, the Sixers have reengaged with the city.

That’s exactly what a city, led by a sad sack, checked-out mayor and mired in decline and incrementalism, needs: A group of civic and business leaders to step up and say they’re willing to double down on Philly. Leave it to a sports franchise to get a civic win on our scoreboard.