If we ever had any doubts about the power of speech, the 2024 presidential campaign should set them to rest. On June 27, President Joe Biden in effect lost the nomination because of a poor debate performance. Last week, media outlets across the nation ranked the presentations of nearly every Democratic National Convention speaker, culminating in the mostly laudatory assessment of Vice President Kamala Harris’s August 22 acceptance speech.

Washington Post columnists did an effective job as speech teachers, grading Harris’s performance in terms of the goals to be achieved and her improvement since the 2020 campaign.

David Von Drehle gave the vice president an A-plus, citing her handling of the fraught topic of the Israel-Hamas conflict:

That moment about Gaza was when I realized how much better she has gotten since her debut on the presidential campaign stage five years ago. And, indeed, one theme of this convention for me is that people can learn to be better speakers. Michelle Obama was solid when we met her; on Tuesday night, she was extraordinary. Pete Buttigieg was tedious five years ago; now, he is charming. And Harris, a very average speaker. To go back to that perilous passage, if she had paused for a moment to acknowledge or push back or even listen to the grumblings that were audible in the room, she could easily have created the negative sound bite to define the night. But she kept going, realizing that momentum was on her side and that the room wanted her to succeed and to bring them back to their bliss. A few people are born with that confidence, but several speakers this week have shown that it can be acquired through hard work and practice.

Von Drehle perceptively analyzes the significance of pauses and pace, as well as words in effective speaking. As an educator, I found it affirming to read Von Drehle’s assertion that expert speaking skills can be taught. “People can learn to be better speakers.”

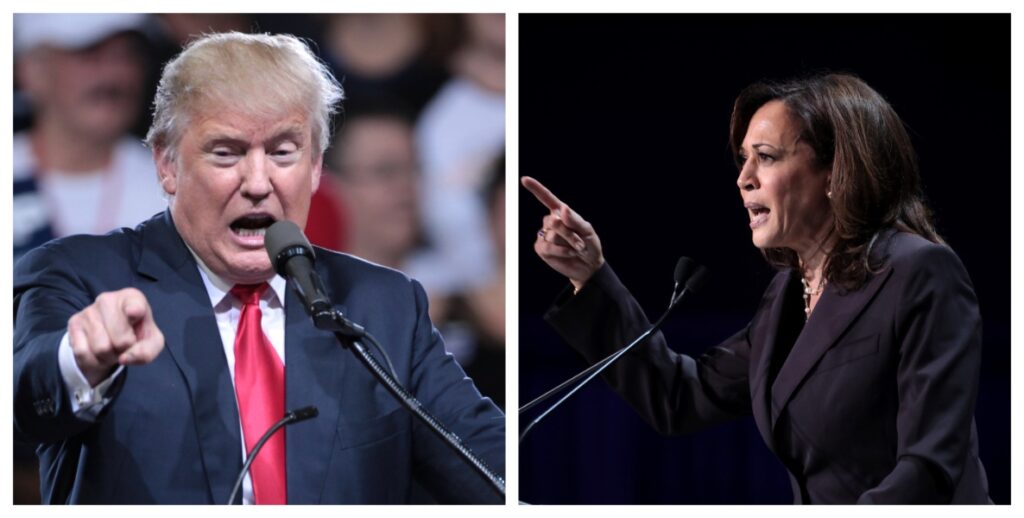

Donald Trump has the speaking skills of a salesman and reality TV host. He has mastered reading a room and responding to its energy, so much so that just a few of his words can literally cause an insurrection. If Trump were a learner, he might realize that such persuasive powers may not last. Diehards continue to be mesmerized, but Harris’s rise in the polls may indicate that the American people prefer someone who articulates as Harris does.

In his acceptance speech at July’s Republican National Convention, Trump spent the first 20 teleprompter-directed minutes effectively presenting himself as a heroic survivor of political violence. But then for the next hour or so, he rambled off-script in ways that even his supporters found less than mesmerizing. We’ll see how Trump orates at the presidential debate, if we have one, and see how he fares in November.

We should teach speaking skills from grade school through grad school

According to Craig Sawchuk, Ph.D., a Mayo Clinic researcher in psychology, “Fear of public speaking is a common form of anxiety. It can range from slight nervousness to paralyzing fear and panic. Many people with this fear avoid public speaking situations altogether, or they suffer through them with shaking hands and a quavering voice. But with preparation and persistence, you can overcome your fear.”

It’s never too early to start helping children feel comfortable as speakers. It’s good advice for all parents to talk and patiently listen to their children. I was exceptionally lucky in my own childhood. My mother always encouraged me to speak up in our talkative adult family, which included a brother and sister half a generation older than I. As a widow without much income, my mom nonetheless enrolled me in what in those days were called elocution lessons. Once a week we traveled from our house on Florence Avenue in Southwest Philly to the downtown studio of retired actress, Mae Desmond, who coached little girls in speaking and acting.

When I was five, I had a role in a radio production of The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew. From that age on, I never felt nervous about speaking before any group. It’s important to note that acting is excellent preparation for public speaking. Inhabiting and expressing yourself through other personae help to prepare you for speaking in your own voice. My very early experience prepared me for a lifetime of having a voice in every endeavor, including university presidencies.

I encourage all of us to work on our own speaking and listening skills. Let’s urge schools and universities to integrate effective communication into the curriculum. By doing so, we may be preparing a young Philadelphian to be a future President of the United States.

Good luck of this sort is rare. But we do have the power to include speech and acting experiences in early childhood education. I urge university teacher preparation programs to include sample lessons to assist teachers in encouraging young children to speak up.

Speech activities should be incorporated up, down, and across the curriculum, grade school through grad school. Every high school and university should offer theater experiences and an active debate club. As a dean at Brown University, I worked with faculty to extend writing across the curriculum to speaking across the curriculum.

When I was the Chancellor of the University of Alaska Anchorage, our university outranked Harvard and Yale in debate. Why? Debate club student leaders personally recruited students in local high schools. They would ask teachers to introduce them to shy students and then encourage them to overcome their fears through debate training and experience. It worked. These bashful kids became debating stars.

What does it mean to encourage strong speaking skills?

Speaking well is not isolated to formal speeches on special occasions. In our everyday lives, it’s important to communicate effectively with everyone from political leaders to restaurant wait staff. Making an effective public comment at a school board meeting, for example, requires speaking, not reading, and making authentic contact with the listeners. It’s okay to have a list of bullet points, but the remarks themselves should be delivered with appropriate eye contact, facial expression, and pauses. Oh, and as many speakers at the two national political conventions illustrated, less is more — almost always. Be brief, get to the point, and sit down. Rambling makes a terrible impression and in the case of political candidates may lose elections.

There’s no doubt that effective oral communication will be crucial on September 10, when Vice President Harris and former President Trump are scheduled to confront each other in Old City’s National Constitution Center — their first presidential debate — at 9pm, hosted by ABC News. What will we learn about the candidates from this confrontation? Beyond conveying information, the debate will reveal a great deal about self-control, character and values.

I encourage all of us to work on our own speaking and listening skills. Let’s urge schools and universities to integrate effective communication into the curriculum. By doing so, we may be preparing a young Philadelphian to be a future President of the United States.

Elaine Maimon, Ph.D., is an Advisor at the American Council on Education. She is the author of Leading Academic Change: Vision, Strategy, Transformation. Her long career in higher education has encompassed top executive positions at public universities as well as distinction as a scholar in rhetoric/composition. Her co-authored book, Writing In The Arts and Sciences, has been designated as a landmark text. She is a Distinguished Fellow of the Association for Writing Across the Curriculum. Follow @epmaimon on X.