Last Friday night, while Connor Barwin and several of his Eagles teammates were rocking out at Union Transfer to support Barwin’s cause of refurbishing inner-city playgrounds, Muhammad Ali was in a Phoenix hospital, taking the final breaths of an epic, stirring life. Barwin and his teammates had come out for a civic cause, not an uncommon sight these days among athletes. In part, that’s owing to the eloquence of Ali’s long-ago example. Of course, the boxer’s foray off the sports pages and into the news was hardly as popular as the civic ventures of today’s jocks.

After all, on the March, 1971, night that Philly’s own Joe Frazier floored Muhammad Ali in the 15th round of the first of their three epic fights, it is said that Richard Nixon, who would go on to be run out of the presidency as the unindicted co-conspirator of a felony break-in, jumped up and down in the Oval Office, celebrating the defeat of “that draft dodger asshole.”

The fight had become much more than a fight; it was a referendum on Nixon’s Vietnam War. Ali was a Black Nationalist, a Muslim, a conscientious objector to the war who, refusing induction, stared down five years in jail. Suspended from boxing while his case wound its way through the courts, he lost nearly four years in his prime before the Supreme Court ultimately ruled in his favor. Frazier, born a sharecropper’s son in South Carolina, had said “politics is a little out of my line” when asked about Vietnam. He—like that otherwise bastion of liberal values, The New York Times—had refused to call Ali by anything other than what Ali had identified as his slave name, Cassius Clay. Ali branded Frazier an Uncle Tom, and saw to it that Frazier came to stand for the war and white America.

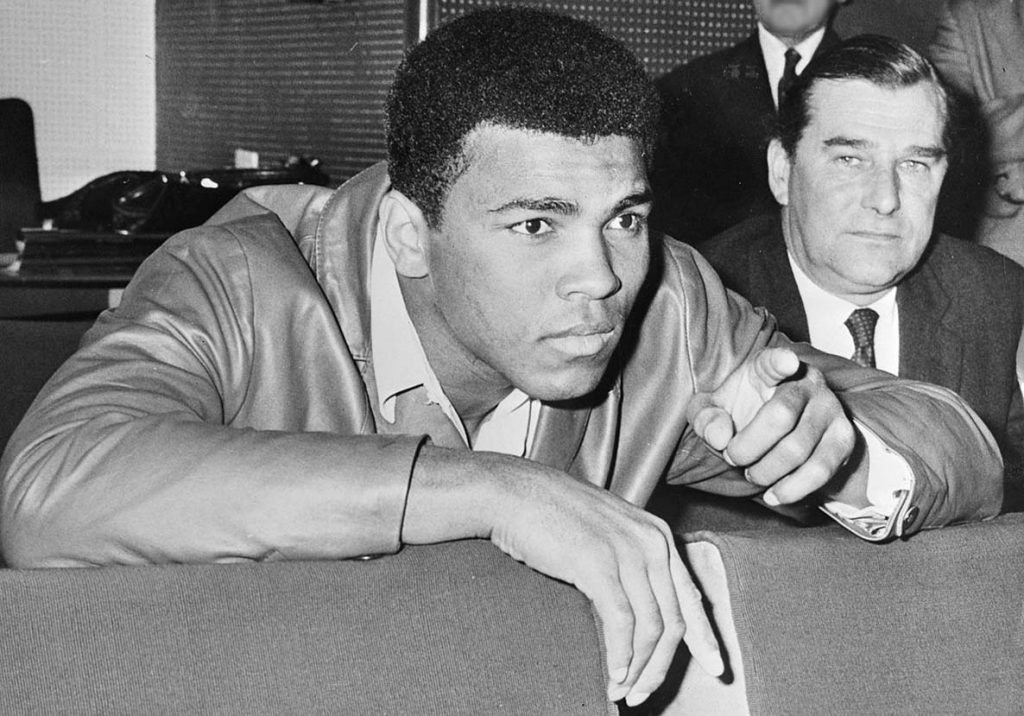

For many of us, Ali was our first glimpse of a brother from another planet, a wholly self-created, larger than life character, a testament to the joyous sense of freedom that could be derived from simply living out loud.

I thought of Nixon when news broke that Ali had died because, when the former president passed away in 1994, there was much hagiography, as there tends to be when we speak of the dead. There was talk of his statesmanship and his political acumen, but it was tougher to find in all the fond reminiscences the Nixon of the Watergate tapes, the sneering cynic, racist and anti-semite. In the days following Ali’s death, the plaudits have predictably come: Ali was a man of peace and love who stood for principle and served humanity. While I agree, and have long agreed, the conclusion runs the risk of whitewashing Ali’s revolutionary persona.

After all, the fawning media coverage of his death stands in stark contrast to the portrayal of Ali in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ali moved first to Philadelphia and then to Cherry Hill. Back then, Ali was given to us as public enemy number one, a threat to the established order, dangerous. It’s worth keeping in mind that the media that has embraced Ali these last couple of decades has done so only after he had lost the power of speech due to Parkinson’s Syndrome; Ali became beloved by those who had hated him only when he could no longer offend.

Mike Marqusee’s Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties arguably makes the best case for Ali as radical social force. Its rebuttal came in the form of Mark Kram’s compelling Ghosts of Manila: The Fateful Blood Feud Between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Kram (whose son, Mark Kram, Jr., wrote for the Daily News and is at work on a Frazier biography) makes much of the fact that Ali couldn’t locate Vietnam on a map or explain what the conflict in Southeast Asia was all about. “For his every utterance, heavy breathing from the know-nothings to the trendy tasters of faux revolution,” Kram writes. “Seldom has a public figure of such superficial depth been more wrongly perceived—by the right and the left.”

Legendary Philadelphia sports columnist Stan Hochman agreed: “I think Ali had only a small sense of the issues of the day and was willing to play the race card against another black man, to force people to take sides, to root for him so he could feed off their passion.” Hochman is right in the sense that what Ali did to Frazier was terrible, turning black America against him, calling him a gorilla and Uncle Tom. And Kram is right that Ali was no policy wonk.

But Ali’s death has sent me scurrying back to these and other books, like The Muhammad Ali Reader, and what emerges is, as I’ve written before, a complicated view of one of the 20th Century’s most important characters. Ali may have been a simple boxer, but he morphed into a moral leader of his times—warts and all. Does one need to know policy in order to become an agent of political change? Ali sensed something about the moment in which he lived, and he withstood swirling cultural winds to symbolize political truths even he might not have fully understood. After all, at a time when few dared oppose the Vietnam war, Ali went on TV and pithily summed up the illogic of the conflict: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong,” he’d said. Watching him, I watched my Dad, a Cold War veteran, muttering to himself in his Barcalounger: “My God, he’s right.”

The fawning media coverage of his death stands in stark contrast to the portrayal of Ali in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ali moved first to Philadelphia and then to Cherry Hill. Back then, Ali was given to us as public enemy number one, a threat to the established order, dangerous.

In keeping with the need to avoid Nixon-like hagiography, let’s stipulate: Going back and rereading the Ali canon, there’s a lot to cringe over. Ali was sexist, owing partly to the times and partly to the Nation of Islam’s codified subjugation of women. And his racial taunting of Frazier—who had helped him out financially when Ali’s court case had all but bankrupted him—was unseemly.

But—and this is what Kram, Hochman, and other revisionists miss—it was also political. It can’t be separated from the context of the times. Marqusee documents that Ali’s appeal of his case against the government cited the exclusion of blacks from draft boards. “In the two states dealing with his case, Kentucky and Texas,” he writes, “only 0.2 percent and 1.1 percent of draft board members were black, although blacks made up 7.1 percent and 12.4 percent of their respective populations.” Ali was pilloried on editorial pages, hated among whites, and even Jackie Robinson criticized him. To make ends meet during his banishment, he went on a college speaking tour, where he’d posit the war as part of a larger racial argument. “We have been brainwashed,” Ali said at Howard University. “Even Tarzan, king of the jungle, in black Africa, is white.”

No matter what the obits say this week, make no mistake: Ali in his prime was an unpopular radical, deemed far outside mainstream America. When, with Malcolm X by his side, Ali announced after first winning the heavyweight title in 1964 that he was a member of the Nation of Islam and would be changing his name, he said something few athletes have ever told a media throng, before or since: “I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” an overt political statement. Into this context came Frazier, insisting on calling Ali “Cassius Clay,” drawing the battle lines. Frazier was the establishment, without even knowing it. “Joe, in his innocence, was representing white America—in his innocence,” football great turned activist Jim Brown said in the 2000 HBO documentary Ali-Frazier I…One Nation Divisible, about the feud between the two men. “And that will incense a revolutionary who is trying to make change and knows doggone well there’s no equality.”

Ali moved to Philly from Chicago in 1970, during his banishment from the sport for refusing induction into the armed services. Stripped of his title and his passport, he watched as Frazier became champion, possessor of what he saw as his title. Some thought the move to Philly was all about getting in Frazier’s head, invading his home turf. After all, if Ali was not the inventor of trash talk, he was certainly its most celebrated practitioner. Before a single punch was thrown, he’d take up residence in his opponents’ heads, like that time he obtained Frazier’s hotel room number the night before one of their fights. “You ready to die tomorrow, Joe Frazier?” he said when Frazier picked up the phone.

Ali stalked his nemesis around town, going so far as to run where Frazier would run in Fairmount Park. During one of the run-ins Ali orchestrated, an exasperated Frazier said, “What you in Philly for? Philly’s my town.” “Oh, I just want to get a little closer to you, honey,” Ali replied.

Ali had been staying in Overbrook, just off City Line Avenue in Philadelphia—I remember him signing kids’ autographs for hours at what was then the City Line Marriott—when his close friend Major Coxson convinced him to move to Cherry Hill. As reported by Maury Z. Levy in a 1975 Philadelphia magazine piece, the reason was—in a comforting nod to how, the more things change, the more they stay the same—the Philly wage tax, which would have cost the then-former champ considerably. Coxson, who was a shady South Jersey character, a candidate for Camden mayor who had done serious jail time and who had quipped, “Most politicians end up in jail anyway, so I’ve got a head start”—would later be executed in his home, gangland style. After his murder, Ali left the area, quickly.

According to Levy’s piece, in the three years he was here, Ali was active in the life of Philly, trying to help calm racial strife at South Philly’s Tasker Homes, visiting hospitals, hiring down-on-their-luck area fighters. “One day he got into training camp late because he heard a thing on the news about this little kid who had gotten his legs cut off by a train,” Levy writes. “He went to the hospital, unannounced, and held the kid in his arms and started dancing around. ‘This,’ he said, ‘is the Ali shuffle. And one day you’re gonna be doing it yourself.’”

When the Supreme Court found in his favor in 1970, it set up the fight of the century, a showdown between the two undefeated titans. Frazier was the champ, but Ali, who hadn’t lost his title in the ring, referred to himself as “the people’s champ.” Frazier was in no hurry to fight, so Ali stalked his nemesis around town, going so far as to run where Frazier would run in Fairmount Park. (Fairmount Park comes up in boxing lore at least one other time, when Sonny Liston, the bad boy champ Ali dethroned in 1964, was arrested in the park for impersonating a police officer by flagging down a female driver with a flashlight; though charges were never filed, the episode prompted Liston to flee town and say, “I’d rather be a lamppost in Denver than the mayor in Philadelphia.”)

During one of the run-ins Ali orchestrated, an exasperated Frazier said, “What you in Philly for? Philly’s my town.”

“Oh, I just want to get a little closer to you, honey,” Ali replied.

One day, the two met up and almost came to blows then and there. They agreed to fight in a Police Athletic League gym; word got out. Over 1,000 people turned up for the spectacle, as did Ali. Frazier was a no-show. Ali held court. “He wants to show he can whup me,” Ali shouted. “He says he’s the champ. Let him prove it here in the ghetto where the colored folks can see it.”

In an interview in a publication called The Black Scholar, Ali explicitly made the connection between Frazier and his own politics, seeing his opponent as a stand-in for his oppressors. “I was determined to be one nigger that the white man didn’t get,” he said. “…I hate to see black women and men, once they get prestige and greatness, where they can go into ghettos and pick up little black babies and make them feel good, to go leave and marry somebody else and put the money in that race…Now the white man’s got the heavyweight champion—Joe Frazier’s got a white girlfriend.”

When Esquire magazine gave Ali five pages to fill, he published a manifesto. “[Black athletes should] take all this fame the white man gave to us because we fought for his entertainment, and we can turn it around,” he wrote. “Instead of beating up each other…we will use our fame for freedom.” Ali suggested diverting $25 million from military spending to build homes in deep southern states. “Each black man who needs it will be given a home,” he wrote. “Now, black people, we’re not repaying you. We ain’t giving you nothing. We’re guilty. We owe it to you.”

After boxing, he found meaning beyond the orbit of his own ego, telling his authorized biographer Thomas Hauser in 1990 that boxing bored him now. “Now my life is really starting,” he said. “Fighting injustice, fighting racism, fighting crime, fighting illiteracy, fighting poverty, using this face the world knows so well and going out and fighting for truth and different causes.”

Can you imagine a pro athlete making an argument for reparations today? Of course, outside agitators have always paved the way for inside change agents. In that sense, there’s a direct line from Ali to someone like Barwin today; as Jesse Jackson used to observe, tree shakers beget jelly makers.

Even if, in retrospect, you find Ali’s rhetoric off-putting—the 1975 Playboy interview in the Ali Reader is full of statements some would classify as “anti-white”—there’s no doubting his stunning originality. He lived life as though he were starring in his own movie, a showman’s showman, and yet he didn’t fall prey to the narcissism of celebrity. In fact, after boxing, stricken with Parkinson’s, he found meaning beyond the orbit of his own ego, telling his authorized biographer Thomas Hauser in 1990 that boxing bored him now. “Now my life is really starting,” he said. “Fighting injustice, fighting racism, fighting crime, fighting illiteracy, fighting poverty, using this face the world knows so well and going out and fighting for truth and different causes.”

For many of us, Ali was our first glimpse of a brother from another planet, a wholly self-created, larger than life character, a testament to the joyous sense of freedom that could be derived from simply living out loud.

Ali was, argued legendary New York art director and ad man George Lois in his book, Ali Rap, the father of hip-hop: “A pugilistic jester whose verbal jabs made more headlines than his punches in the ring, his doggerel was an upscale version of street trash talk, the first time whites had ever heard such versifying—becoming the first rapper, the precursor to Tupac and Jay-Z. His first-person rhymes and rhythms extolling his hubris were hilarious hip-hop, decades before Run D.M.C., Rakim and LL Cool J. His style, his desecrating mouth, his beautiful irrationality, his principled, even prophetic stand against the Vietnam War, all added to his credentials as a true-born slayer of authority.”

Ali’s creativity in the ring was rivaled by the inventiveness with which he lived; his whole life was a kind of performance art, with him winking at his audience all the while. As Lois documents, he’d often burst into verse, sometimes extemporaneously; his most famous, of course, was ”Float like a butterfly/Sting like a bee/ His hands can’t hit/What his eyes can’t see,” but there were many more, including: “I’ve wrestled with alligators/I’ve tussled with a whale/I done handcuffed lightning/And thrown thunder in jail/You know I’m bad/Just last week, I murdered a rock/Injured a stone/Hospitalized a brick/I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.”

But perhaps it’s most fitting to end with Ali’s poem about none other than his great Philly rival, Frazier, which captures so many facets of his personality—the bemusement, the showmanship, the deftness of his language. Watch below for a glimpse of a true American original:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6xiw6BBJB2w