“I’m a big fan of audits,” says Philadelphia City Councilmember Mark Squilla. (And no one else, ever.) “I know people don’t like when they’re audited,” he continues, “but I look at it differently. An auditor is there to show you what you’re doing right, and maybe what you can improve on.”

During his four terms in office, Squilla has been a mild-mannered presence around City Hall, better known for his attentive constituent services than his leadership or outspoken opinions. While it’s true some minor controversies have followed him — such as the time he angered condo developers by pushing sprinkler legislation or his (unsuccessful) fight to keep recognizing Columbus Day — Squilla has fit the mold of a pragmatic, old-school, retail politician. But it’s a long entry on his resume before the time on Council which I’ve just asked him about, prompting him to recall his South Philly upbringing.

“Growing up, I was a really hyper kid. I guess they would call it ADD now, but back then it was called ‘no self control.’ I struggled with reading, so I geared myself more toward math and logical thinking,” he says. “It drew me to writing programs. And I think computer science helped me mold my philosophy, why I do things the way I do now.”

For 25 years, beginning in the mid-1980s, Squilla wrote computer code while working as a systems analyst in the Pennsylvania Office of the Auditor General. All these years later, he tries to emulate that approach as best he can in his governing. “What I liked about [programming] is you knew the end outcome when you started,” he says. “When you write a program, you have to put all these checks and balances in the middle to make sure you get the results that you want at the end.”

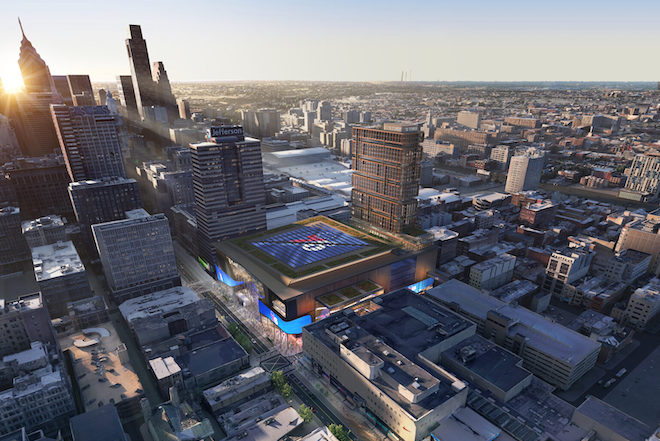

How Squilla intrinsically solves problems has increasingly come into public view over the past year and a half. That’s because he represents the 1st District, where the 76ers want to build a brand new arena, controversially, on the edge of Chinatown. And more than any single person in the city — above the mayor, the team’s owners, even ubermensch Jason Kelce — Squilla’s final word matters.

Due to century-old traditions of how business gets done in Philly — namely councilmanic prerogative — he holds the power to stop the project in its tracks or push it forward if he wants. How does the fate of a $1.55 billion arena end up resting on the shoulders of a single councilmember — and why?

Kingmaker or executioner?

Although it’s deeply unpopular among the majority of Philadelphians, councilmanic prerogative is a firmly established tradition in Philly. It’s not illegal, but it’s also not law. Often referred to as a “gentleman’s agreement,” it’s a custom that gives all 10 District Council members the authority to de facto approve or veto any projects in their areas which pertain to zoning or land use. In essence, it’s a tradition of deference among our elected officials: You stay off my lawn, I’ll stay off yours.

In theory, other members can vote down major development projects at their discretion; in theory, the mayor could obstruct them. In practice, however, nobody successfully challenges the will of District Council members. When Pew researchers analyzed the phenomenon of councilmanic prerogative in a 2015 report, looking at a six-year sample size, researchers found that 726 out of 730 projects in which councilmanic prerogative was cited were passed unanimously. Six dissenting votes by individual members (in six years!) were cast, as they found “no recorded cases in recent years of a prerogative vote going against a District Council member.”

“I know people are going to be upset with whatever decision we make, but they’re not going to be upset about the process and the time it took us to get to that decision-making point.” — Mark Squilla

In the years since the study was published, the trend within the entire body has held true, though some of the newer members have expressed a desire to reform the practice or voted by their lonesome while breaking ranks with a zoning decision, so there have been a few more chinks in the armor.

Squilla is not only a big fan of audits; he’s also a big fan of this much-maligned tradition, a position held by most of his colleagues. “I think councilmanic prerogative gets a bad name,” he says. “The people in that area can vote you in or out, right? They don’t like your decisions, they can mobilize against you.”

When wielded authentically, councilmanic prerogative can be a way of preserving Philly as a “city of neighborhoods.” It can be a tool for curbing gentrification and creating leverage for communities to shape a project more to their liking, as the Pew report described: “Many have used that influence to persuade builders to alter proposed developments — for instance, by reducing scale or adding parking spaces — to make them more pleasing to the residents who live around them and … to offer ‘community benefits,’ such as financial assistance to a neighborhood.”

Of course, just because Squilla can invoke prerogative powers, it doesn’t mean that he has to. He insists that any arena vote — if it comes to a vote at all — will take place in the Committee of the Whole, allowing every member a say in an open hearing. That sounds fair and transparent in theory, but in reality, it’s unlikely any of Squilla’s colleagues will risk their own future projects by voting against one in his district.

“This is going to be more of a citywide approach if we move it forward, but I still believe the City Council person in the district should be the one who’s going to be held accountable for that decision,” says Squilla.

As Jon Geeting wrote for the Citizen, councilmanic prerogative undermines the City Planning Commission, the Zoning Board, and the entire citywide apparatus designed to provide checks and balances. “Everybody can point to an instance where councilmanic prerogative has come in handy in a pinch, but it also has a tendency to place members at the center of lots of deals they shouldn’t be a part of, illegal or not,” Geeting wrote.

Both the potential and proven downsides of prerogative are not hard to grasp. The tradition opens the door to backroom dealing and bribery, while closing the door on transparency. In fact, 6 out of 7 members of Council who’ve been convicted of a crime since the 80s were ensnared by illegality related to councilmanic prerogative. (Former councilman Bobby Henon was convicted on charges unrelated to development, while Council President Kenyatta Johnson and his wife were recently acquitted of charges stemming from their use of privilege around a land-use deal.)

Even when there’s no chicanery involved, it seeds doubts about our city government. As even 3rd District Councilmember Jamie Gauthier noted to WHYY shortly after she was elected (and a couple years before she was sued by a developer over her use of prerogative): “When you have this tradition where you are almost solely abdicating issues around land use and land disposition and zoning to one person, I think it’s kind of ripe for misuse or even just the appearance of misuse.”

Although critics of the custom point to its ability to either fast-track or stop a project in its tracks, councilmanic prerogative can help to elongate the process as well. Squilla thinks that a slow burn, in this case — getting as many inputs and opinions as possible, both pro and con — is necessary to come to a decision on the 76ers arena. Although the Sixers originally gave Council a deadline of the end of the 2023 to reach a decision (the team vaguely raised the idea that they could move outside city lines, without approval), Squilla is fine with a more deliberate pace.

“My goal is to make sure the end result is making sure that Chinatown is thriving, the businesses survive … and making sure that affordability and not displacement is a part of this project,” Squilla says. “I know people are going to be upset with whatever decision we make, but they’re not going to be upset about the process and the time it took us to get to that decision-making point.”

Getting down to it

When I first entered Squilla’s office in February to discuss the arena, he was standing up eating a salad for lunch. It was a fitting snapshot of Squilla, who is known for his abundant energy and omnipresence around a sprawling 1st District, which includes not only Chinatown, but also parts of South Philly, Kensington, Northern Liberties, Center City and most of the Delaware River waterfront.

Ever since the 76ers announced their plans for the arena in late 2022, a lot of that energy has gone towards conversations around the project. “This has probably been the most lobbied process that I’ve been involved in,” Squilla says, rattling off some of the many interest groups he’s been meeting with on the regular. They include vehement opponents like the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (a nonprofit whose survey last year found 93 percent of the surrounding businesses opposed the project) and the Washington Square West Civic Association (whose own survey found 77 percent of residents don’t want the arena). They also include major supporters of the arena, like members of the Black Clergy and the building trades, the latter being a significant booster of Squilla throughout his time on Council.

Given the high stakes, it’s led some people to wonder, too, if there will be lasting consequences for Squilla, who at 61 years old will likely be the subject of retirement rumors heading into the next election cycle. Assuming he seeks a fifth term, could the arena make him vulnerable? Although he ran unopposed in last May’s primary, Squilla initially faced a progressive challenger in former Reclaim Philadelphia Political Director Amanda McIllmurray, who ultimately switched to an at-large candidacy after receiving pressure from established members of the Democratic Party and the unions.

Squilla is the second-longest-tenured Democrat on Council (tied with Kenytatta Johnson and Cindy Bass, and shy of Curtis Jones’ seven terms), and the short-lived challenge highlighted the complex demographics within his district. Two of the city’s highest turnout wards in recent elections — Wards 1 and 2, both located in South Philly — are not only part of Squilla’s district, but also hubs for white-collar young professionals who’ve recently elected progressive-minded state Senator Nikil Saval and Representative Elizabeth Fiedler. Along with opponents in Chinatown and Wash West, pleasing South Philly progressives will be a difficult task for Squilla unless he ultimately disavows the arena.

“I think councilmanic prerogative gets a bad name. The people in that area can vote you in or out, right? They don’t like your decisions, they can mobilize against you.” — Mark Squilla

Meanwhile, a “no” could disrupt Squilla’s long-standing relationship with the building trades, a potent voting bloc who’ve embraced the arena and the team’s promise of 10,000 construction jobs, plus the untold numbers of Philadelphians who also support the project. It would also be something of a surprise to many observers. The African American Chamber of Commerce has also endorsed the project, after reaching an understanding with the 76ers which lays out the team’s investment in Black-owned businesses throughout the building and operation of the stadium. And although the Mayor has not publicly expressed her support, she is also closely aligned with — and to some degree beholden to — the building trades.

Although the arena proposal is politically charged, Squilla isn’t ruling out a compromise with the surrounding community which could offset their concerns. He’s repeatedly said that if the project were to move forward, there would need to be a community benefits agreement (CBA) that is codified in legislation, addressing things like rental assistance (to offset rising costs in the neighborhood from the arena), traffic control, trash and safety. (The 76ers have already proposed a $50 million investment in the form of a CBA.)

When the casino along Delaware Avenue (now Rivers Casino) was initially proposed, Squilla was still an unelected civic leader, but he remembers hearing a chorus of critics who said it would alter the fabric of the neighborhood, bringing along with it crime, traffic, and prostitution. After a long legislative process involving his predecessor, Councilman Frank DiCicco, neighborhood groups brokered a community benefits agreement with the casino operators which led to more than $10 million in donations from Rivers to fund the Penn Treaty Special Services District, a nonprofit controlled by members of the surrounding neighborhoods. As a councilman, Squilla says that the compromise has paid dividends to his district.

“The casinos had zero support whatsoever,” Squilla said. “And the casino actually became a great community partner to lift up the neighborhood. So, you know, these decisions are hard decisions.”

Of course, the arena is a project of greater magnitude, with an inordinate amount of considerations to weigh, begging the question of what Squilla’s North Star will be. “The people closest to it do have a more influential say,” Squilla says, speaking of Chinatown businesses and residents. And he’s insisted that if and when he’s ready to move forward with the project, he’ll give Chinatown at least 30 days to review the legislation before submitting it to Council.

Still, Squilla says he needs much more information before he’ll come close to making a decision — including whatever will be contained in the delayed, but highly anticipated “impact studies” being conducted by consultants hired by then-outgoing Mayor Jim Kenney, and paid for by the Sixers. The studies, looking at the economic and community effects of the arena, were supposed to become public by the end of last year, but now are expected sometime this spring.

Insiders predict those studies will be non committal, but Squilla listed a litany of concerns he’s looking to see addressed in the reports: “Is the city even able to have two arenas in the city, and both of them be able to survive and sustain themselves? What are the tax revenue gains? Is it just a swap of revenue from one location to another? Or is there actually an increase in revenue that would be generated by having two arenas? And then you have the community impacts — how are the adjoining community stakeholders impacted?”

For now, the public only has these Hamlet-like ponderings to guide development in the city, including what might be in store for the arena, thanks to councilmanic prerogative. But Hamlet was not ever a king. Only our district council members are.

Squilla acknowledges that the decision-making is taking longer than expected, but for now, he’s trusting the process. “I believe before the end of this year, there will be a decision whether to move forward or not,” he says.