Jeremiah White wasn’t always a science nerd. Coming up as one of the only black kids in a virtually all-white school in Bucks County, no one really expected him to master any of what are now called STEM fields. And he didn’t develop an interest until near the end of his high school career, when he suddenly realized that he could work through science and math problems like nobody’s business if he put his mind to it.

Being African American, though, made things difficult when he developed his sudden inclination toward science.

“They didn’t believe I could be that good,” says White, an entrepreneur and consultant, who is also the board chairman of the Community College of Philadelphia. “They checked inside my desk sometimes to make sure that I wasn’t cheating.”

It’s this early experience, says White, that led him to start iPraxis, a 13-year-old nonprofit that provides hands-on science learning and mentorship for underserved Philadelphians, particularly students of color. White, a former teacher, tech entrepreneur and nonprofit head, went to school decades ago. But in all these years, little has changed.

In fact, the state of diversity in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math fields—referred to ubiquitously as STEM—is absolutely dire. A study released in 2015 revealed that more than 80 percent of engineering, computing and advanced manufacturing jobs were held by white or Asian workers, compared to below 17 percent of African-American and Latino workers. And perhaps more importantly, underrepresented minorities—Latinos, Native Americans and African Americans—earn only 11 percent of college engineering degrees. And it’s a problem that is easily noticeable in Philadelphia: In a majority-minority city with more than a handful of world-class universities and tech startups, you don’t need to perform an intensive study to see that the scene is overwhelmingly white.

White had always been aware of how rare his color was in the tech field. But the straw that broke the camel’s back came a few years ago when he led the Osiris Group in the University City Science Center, a marketing group that worked largely with the Science Center’s independent labs. As chairman of Osiris, White interfaced with a whole slew of different scientists, and enjoyed the work—he is, after all, a self-avowed science nerd. But he was blindsided by the astonishing whiteness of the folks he worked with.

“I consider it to be structural racism,” says White. “It’s all led us to this point where we have so many young people who are not equipped to function in this new reality. They can’t pass the union tests because of the math. They can’t pass the police test because of the math. Our job is to try to convince them that yes, they can in fact do this.”

“I didn’t see very many Hispanics, African-Americans or Native Americans engaged in the research, or in commercialization, or as IP lawyers or as people supplying equipment in the labs,” White says. “And when you looked at it, this place has the third-largest presence of bio-science labs in the country, and the representation of people of color was, frankly, minuscule.”

So White took it on himself to try and make things right. He lobbied some business partners for assistance and donations, and received a grant from the state of Pennsylvania to identify minority-run businesses that were working in the commercialization of technology and doing business with labs; these were the first steps of the fledgling iPraxis. It was through the study—called “Pathways”—that White determined that a major impediment to underrepresented minorities working their way into STEM fields was, simply, that minority kids were less exposed to STEM fields in grade school than their white counterparts, and that the exposure that they did receive to STEM fields was notably cursory.

“We looked at the Philadelphia public school system, and tried to figure out what was going on with the percentage of students who were coming out of there who were prepared to go into STEM-related work,” says White, who is from Buckingham. “Why weren’t Philadelphia kids coming out of school ready to study science?”

iPraxis and Penn conducted a study together, which found that Philadelphia public schools—general lack of funding notwithstanding—let down science students in one or two notable ways, first and foremost being that, while kids were being made to do science projects and labs, they were given little context for understanding the content of those labs. To put it simply: White and company found that a Philadelphia student would, hypothetically, be likely to have assembled a potato clock over the course of her or his educational career, but wouldn’t be able to delineate why it is that a potato clock works.

“So myself and a number of other African-American business and science people got together and said ‘What can we do about the fact that the school system isn’t putting out students who can compete in bio-science?’” White recalls.

The next move involved two steps: deciding which age group of kids to target, and what curriculum to target them with. White says figuring out which age group to target was the easier task—the available data, he says, made it obvious that middle school kids were the most important to target, considering that African American dropout rates spike in the 9th grade. The question then became how to convey science as a fun, involved and gripping prospect to kids who had been less-than-enamored with their school system’s anemic science curriculum.

More than 80 percent of engineering, computing and advanced manufacturing jobs are held by white or Asian workers, compared to below 17 percent of African-American and Latino workers. And perhaps more importantly, underrepresented minorities—Latinos, Native Americans and African Americans—earn only 11 percent of college engineering degrees.

“We realized that we were working in an ecosystem with a lot of knowledge-based businesses,” White says. “We could do it Doctors Without Borders- or Habitat For Humanity-style, get students and professors to volunteer.”

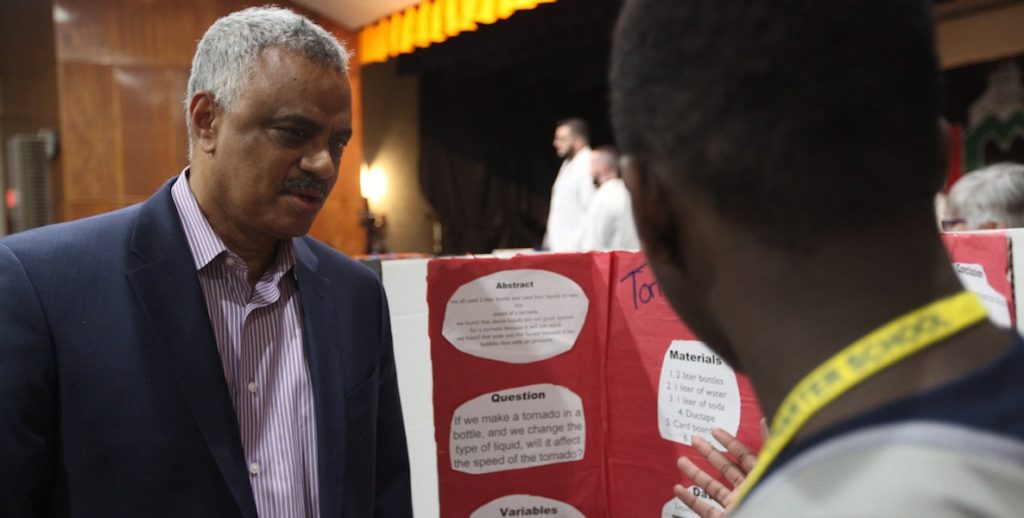

After a period of what he calls “informal study,” iPraxis arrived at the notion that science fairs (yes, the seemingly-antiquated kid science convention kind) shepherded by those volunteers from schools like Temple and Penn, could be a way to get kids more involved with scientific processes as well as teach them vital basics, like the scientific method—the kind of stuff, White says, that appears on virtually any standardized test. In preparing to compete, students learn the ins and outs of their projects, and gain learn-by-doing science lessons in the process.

iPriaxis launched its program about a decade ago, when science fairs were roughly, I don’t know, 30 years past their prime. The mid-naughts weren’t about baking soda volcanoes when it came to education; it was all computerized learning and clunky electronic whiteboards and those pens that could automatically tell whether your penmanship was good or terrible. In short: Science fairs weren’t the hottest bet when it came to the notion of changing education for the better.

And yet, White’s gamble paid off. Now, iPraxis works directly with the Philadelphia School District in proliferating its science fairs and other programs; its partners include the University of the Sciences and the Penn Department of Bioengineering. (The group is funded through private and corporate donations, including from Lenfest Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, and Cancer Treatment Centers of America.) According to White, the group has judged and helped assemble thousands of science fair projects in Philadelphia; they’ve since branched out from science fairs, and now do field trips and workshops for science-inclined Philadelphia kids as well.

While iPraxis doesn’t have statistics on hand that say whether the program has had a net positive effect on Philadelphia kids entering STEM fields, White says kids who participated in the program claim that it’s changed the trajectory of their lives. One participant, he says, took a science project fostered by iPraxis to a major, national science fair competition; more than a few have told him that they’d decided to go into STEM fields after participating in one of iPraxis’ programs.

But White is quick to remind that this isn’t all a story of rosey-cheeked sticktoitiveness and educational improvement. iPraxis, he says, is, in the course of introducing kids to STEM fields, battling something far more insidious.

“I consider it to be structural racism,” he says of the factors that combine to keep minority kids out of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. “This is all part of combating that structural racism. It’s all led us to this point where we have so many young people who are not equipped to function in this new reality. They can’t pass the union tests because of the math. They can’t pass the police test because of the math. Our job is to try to convince them that yes, they can in fact do this.”