Early January: My 50-something-year-old sister is diagnosed with glioblastoma. Glioblastoma (GBM) is the type of rare primary brain tumor that felled John McCain, Beau Biden, and, for you Phillies fans, Tug McGraw and Darren Daulton. Only 3.21 people out of 100,000 get GBM. Most of those people are White men over age 64, which my sister is not.

But this is not a story about glioblastoma, really. It’s about an all-American struggle to get health insurance to pay for treatment for it.

But first: brain cancer. A highly academic, thorough medical perspective from someone who got a B- in a college course called “baby bio.”

Glioblastoma is widely regarded as the shittiest form of brain cancer — brain cancer being arguably overall the shittiest form of cancer — and cancer absolutely being all-around fairly totally shitty. GBM is so incredibly, shit-stirringly shitty, in fact, that one night, my sister is admitted to Penn’s emergency department. The next, she’s undergoing an 8-hour surgery within view of Franklin Field.

Last year, 38 percent of Americans — close to 128 million people — said they postponed medical care because of cost. Of these, 27 percent delayed care for serious conditions.

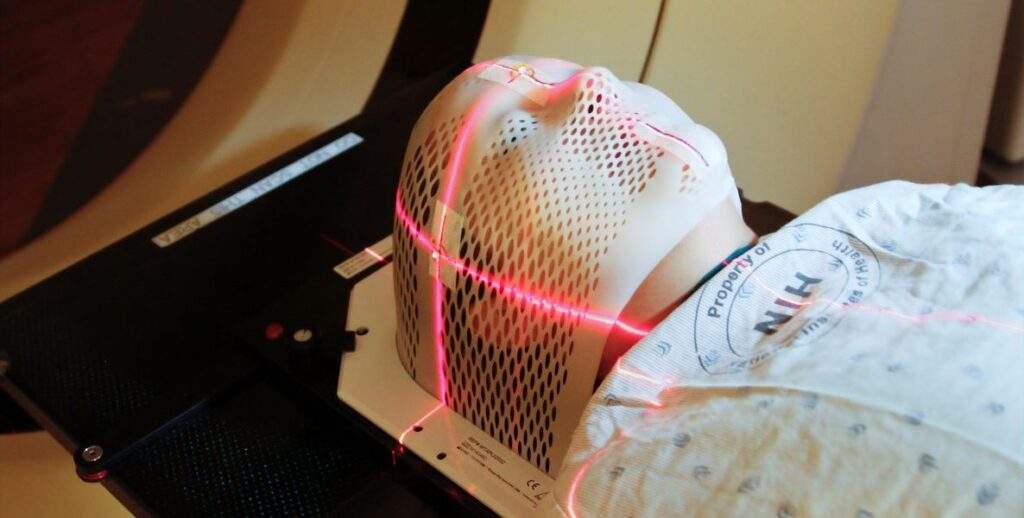

As far as surgeries for incurable brain cancers go, my sister’s is a success. Her surgeon and his team from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) remove all the tiny little shitty bits of 3 cm tumor that their microscopes can perceive. The next step: chemotherapy and radiation, a regimen of daily chemo pills and 30 sessions — or “fractions” — of radiation — preferably, proton therapy, one of Penn’s specialties.

Proton therapy: the good stuff

The two main reasons my sister is a prime candidate for proton therapy, her oncology team tells us, are: 1. Her surgery resulted in a “complete resection,” leaving a clearer indication of where there are most likely 2. minuscule GBM leftovers that grow very quickly and all-too intractably. Also, my sister is relatively young and otherwise very healthy, a nonsmoker with no preexisting conditions and physical fitness to spare.

She’s also a professional, a contributor to her community, a parent to a high school senior — and Penn’s newest participant in a clinical trial that uses AI imaging to map out the delivery of a larger amount of radiation in precise points in the brain where remaining, imperceptible GBM cells are most likely to be lurking.

More than 100 million of us are already deep in medical debt. We are cutting back on essentials, exhausting our savings, taking on more work, going into bankruptcy because of insurance and medical bills.

Precision is the point of nuclear-powered proton therapy. Her other powerful radiation option: photon therapy, aka intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), uses electromagnetic x-rays to attack the cancer but also tends to hit many healthy cells. In brains, this can cause necrosis, which, in turn, can cause permanent impairments in strength, sensation, speech — and secondary cancer, for god’s sake.

Meanwhile, we learn, some of the proton therapy recipients in the clinical trial whose cases resemble my sister’s have already outlived their prognoses. Our family and friends feel incredibly lucky that Penn offers proton therapy, the best stuff for this — I’ll say it again — shit cancer. Few places do.

Photon, proton, tomato, tomahto

Not everyone believes in the efficacy — and therefore the cost-effectiveness — of proton therapy. Although it’s been around for decades — the FDA approved in 1988 — it still has its doubters. PBT centers are expensive to build and install — from $25 million to $100 million — which also makes PBT expensive to deliver and research.

For decades, the medical community has been trying to get a definitive handle on what and how much and for whom proton therapy works best. For now, the consensus is that proton therapy is virtually essential for children with primary brain tumors, because their brains are still developing. It’s also preferred when extreme accuracy is called for.

The treatment continues to gain global traction. There are currently 41 proton therapy centers in the U.S., 89 worldwide, and more on the way.

Penn opened its first proton therapy center in West Philly in 2010 and their second in 2022 in Lancaster. They’ll soon unveil their third, in partnership with Virtua, in Voorhees, NJ. Not to be outdone, Jefferson has the go-ahead from the City to open its first in Torresdale. Yale’s planning one too.

The majority who are suffering physically and financially from lack of healthcare access are people of color.

As for my sister’s team, they believe in proton therapy for glioblastoma patients so much, that for the GBM patients enrolled in their dose escalation study, these docs could not, ethically, include a control group that received only IMRT. This is because, we learn, of “equipoise.”

Equipoise is, according to a 1987 copy of the New England Journal of Medicine that I do not have lying around, “a state of genuine uncertainty on the part of the clinical investigator regarding the comparative therapeutic merits of each arm in a trial. Should the investigator discover that one treatment is of superior therapeutic merit, he or she is ethically obliged to offer that treatment.”

To me, this means: Since Penn’s cancer docs are confident PBT is better than IMRT for GBM, they are morally obligated to give PBT over IMRT people with GBM — and PDQ.

Claim. Denied.

When my sister’s oncology team sees that her insurance is Blue Cross, they are, if not psyched, then relieved. They have lots of Independence Blue Cross subscribers who get proton therapy. (A representative from IBX would not comment on its proton therapy coverage policy or relationship with HUP.)

Except before radiation starts, Penn realizes: My sister does not have Independence Blue Cross.

She has Horizon, another member of The Blues on the other side of the once-blue Delaware River. And, despite Penn submitting a preauthorization for PBT, the day before she is scheduled to start it, she gets a letter from Horizon.

They deny coverage for proton therapy.

So, the next day, my sister begins IMRT/photon radiation, the second-best option to thwart fast-growing GBM cells. Meanwhile, we figure, Penn will appeal the denial, and she’ll be moving onto those proton jawns in a few days.

After all, Horizon’s office-dwelling box-checkers surely know they cannot know better than the world-class oncology team who works on the frontlines of this shit cancer and has spent hours reviewing my sister’s case and is ethically obligated to give her their best treatment.

Or can they?

What happens next

- Penn appeals in writing.

According to a 2021 Kaiser Family Foundation study of people who with health insurance through the Affordable Healthcare Act (ACA), only two-thirds of 1 percent of patients whose claims are denied appeal their denials. According to a recent report from Pro Publica, only 5 percent of Cigna customers who are denied medical claims appeal Cigna’s denials.

In other words, insurance companies can bank on the fact that patients, especially those who are focused on their conditions, or job(s), or families, or a billion other things, won’t have the energy or temerity to challenge them to pay up. On the other hand, according to the Kaiser study, 41 percent of ACA patients who appeal denials go on to be approved for their procedures. Not perfect — but not hopelessly horrific.

- Horizon denies coverage again.

- My sister’s radiation oncologist requests a “peer-to-peer.” This is a real, live, phone call, doctor-to-doctor — specifically with another radiologist. She does this because health insurance companies have become sort of notorious for using non-specialists — even non-M.D. “medical experts,” including third-party consultants, to decide health benefits in complex cases. These experts don’t always make the right calls — or understand the calls they’re making.

“Everybody is having problems with benefits determinations,” says Liz Gardner of the American Society of Radiation Oncology. “We have staff members on the phone with insurers asking, Why are you making your own rules? We are doctors.”

- A few days and a 20-minute peer-to-peer later … Verbal denial.

- Within three business days, somewhere in a room or on a Zoom, Horizon gathers an unidentified group to review and … confirm their denial.

Denied a third time. Shitty on top of the already shittiest. Also, ominously biblical.

Now, I’m pissed — screaming-in-the-car-with-the-windows-up pissed.

- Penn submits another appeal.

- While we’re waiting, I decide to use my meager status and skills as a reporter to ask the Newark, NJ-based insurance company how they know more than my sister’s kickass oncology team in Philly.

I reach Horizon’s communications guy, who sends a lot of information, some of which is … inaccurate. For example, he tells me, in writing, that the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) does not support proton therapy to treat primary brain tumors.

In fact, ASTRO has supported and does support proton therapy for the type of tumors my sister has. See for yourself on pages 4 and 5 of their “model policy,” (where her and all central nervous system tumors are called “CNS tumors.”) ASTRO’s Gardner confirms this.

(This is now what I do for fun, BTW: Read model policies and academic articles featuring lists of health insurance companies that do and don’t cover PBT for certain types of cancer.)

8. Two-thirds of the way through my sister’s five-days-a-week radiation treatments, we learn what maybe you already knew: The other way to get proton therapy is to just pay for it ourselves. Digging into her retirement account, my sister writes a $15,000 check to HUP. She undergoes her first two of 10 remaining fractions, proton-style.

Why did this happen?

Misery might love company, but there’s no solace in knowing my sister has been one of millions of Americans denied health care for any reason — and there are many reasons, the vast majority related to $$.

Last year, 38 percent of Americans — close to 128 million people — said they postponed medical care because of cost. Of these, 27 percent delayed care for serious conditions. It’s no wonder: More than 100 million of us, according to Kaiser Health, are already deep in medical debt. We are cutting back on essentials, exhausting our savings, taking on more work, going into bankruptcy because of insurance and medical bills.

Not surprisingly, the majority who are suffering physically and financially from lack of healthcare access are people of color. (This is why in 2020, The Citizen teamed up with RIPMedical Debt to eliminate $6,104,787 in medical debt for 3,573 Philadelphians over the past two years.)

Thirty million Americans are currently uninsured. Health insurance, despite the Affordable Care Act, remains unaffordable for many.

Thirty million Americans are currently uninsured. Health insurance, despite the Affordable Care Act, remains unaffordable for many. Last year, the average annual cost of employer-provided health insurance for one American was $7,911; for a family, it was $22,463. This is just not feasible for too many of us, especially here in Philly, where 25 percent of us lives in poverty.

But here’s how nuts our health insurance system is: My sister is, luckily, solidly middle-class. She owns her home. She gets her hair done regularly. She has a … golden retriever. She’s not in debt. She also has paid at least $100,000 into various health insurance plans over her career. She has paid for this coverage gladly — and, as an HR executive, has helped companies purchase and employees sign up for these plans — in the off-chance that one day before she turned 65, she would need some of that money back, which, after all, is the sole purpose of health insurance.

And yet, she still ends up on the wrong side of healthcare divide … simply because she lives on the wrong side of a river. (No offense, Jerz. Love you.) For reals though: Philly-based Independence Blue Cross policy covers proton therapy for glioblastoma. Newark-based Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield policy, part of the same “supraorganization,” does not.

How does this make any kind of sense?

According to Philadelphia health insurance executive-turned-whistleblower Wendell Potter, it makes sense only to the people making the profit. In the last decade, our country’s biggest health insurers have made serious bank by swelling costs for plans and deductibles and, according to that ProPublica report, bulk-denying claims.

Potter points to United HealthCare, which earned $28.4 billion profit — from a revenue of more than $300 billion — last year alone. “No insurer has ever made that kind of money in U.S. history,” he says. Also, for the first time in our history, health insurance C-suiters are appearing on most overpaid CEO lists. These guys rake in tens of millions each year as regular guys choose between groceries and cancer care.

“The insurer’s major interest is to protect themselves from high costs,” says Sara Collins, senior scholar and a V.P. at The Commonwealth Fund, a foundation that supports research to make healthcare equitable and accessible. In a few weeks, The Fund will launch a survey about medical costs and health insurance, with a focus on denials of preauthorized care and other claims.

“The insurer’s major interest is to protect themselves from high costs,” says Sara Collins, senior scholar and a V.P. at The Commonwealth Fund,

The reason for the study? The denial trend is clearly “emerging” says Collins. She’s unaware of any general effort or legislation that will, one day, force health insurance companies to cover their subscribers’ healthcare. But, she says, “It’s something policy makers should pay attention to.”

“The purpose of health insurance is to provide us timely access to healthcare when we need it. Most of the time, people don’t use very much healthcare. Most people are relatively healthy. You pay your premiums, and you are protected against the risk of having a serious illness,” she says.

“So, when people encounter problems like this, it’s very disheartening. It places the burden of appeal on the patient, at a point in their life where they’re dealing with a life-threatening illness.”

Where we are now

Two business days after my sister writes a check to Penn for proton therapy, she gets a call from Penn’s radiation oncology authorization department. Horizon has reversed their decision. With no explanation, the utilization management department of Jersey’s largest health insurance company very belatedly agrees to cover her proton therapy. Again, my sister has already completed two-thirds of the second-choice radiation, paid for the last third of the first-choice radiation herself, and now … What?

We may never know why Horizon changed their minds. Did someone smarter than the previous decider take a closer look at her case, and realize a mistake was made? Did my involvement make a difference? Is three the magical number for health insurance appeals?

Whatever the reason, this surely happens because my sister and HUP kept at it. They used their time, access, expertise — privileges — to get a portion of my sister’s healthcare paid for — or, in this case, reimbursed.

Our efforts pay off. They shouldn’t have been necessary in the first place.