One week ago today, Vice President Kamala Harris was back in Philly, this time to speak to a small gathering of the National Association of Black Journalists. The event took place at WHYY, with both NABJ members and communications students from nearby universities in attendance. I was one of the students. I’m in my first and only year of graduate studies in journalism at Temple University.

When I reached the registration desk, I got my name checked off a list by a volunteer, while the NABJ Student Representative next to me received a green wristband. I didn’t know what it was for and I didn’t ask. Once inside, however, I ran into a classmate who broke the news: “The only room is unfortunately … in there,” she said, pointing to a conference room away from the cameras and stage. There were black curtains drawn over the windows. Inside, a projector read “NABJ conversation with Kamala Harris.”

As it turned out, I got dressed up to watch a livestream.

It was the second time in less than a day that I came to terms with missing out on a glimpse of the Democratic nominee for president. Earlier that Tuesday, I went to Community College of Philadelphia to report on a voter registration event. But when I arrived, I saw her large tour bus parked in the middle of the campus. I didn’t even know Harris was going to be there. She was meeting with student canvassers at a separate event. At least I’d see her later, I figured.

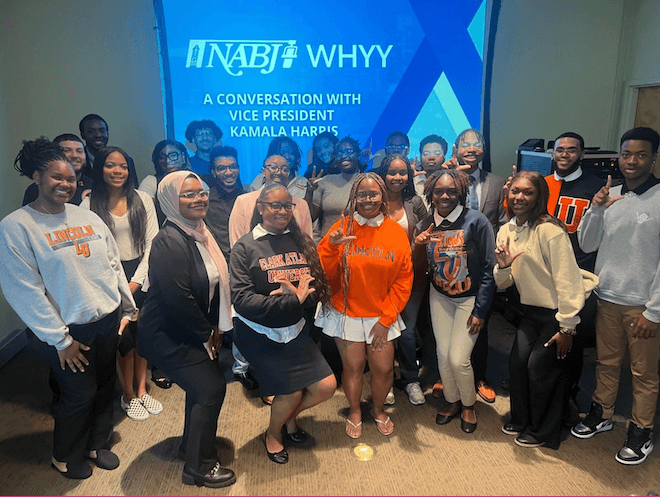

Being stuck in the overflow room was a huge letdown, but I thought about the people in the room who had traveled from out of state. They settled for taking pictures in front of the projector screen, waiting for the event to start. When Harris took the stage, there was an undeniable buzz in the room. (But not too much of a buzz: We’d been warned that any loud noises or protesting would result in people being removed from the building.)

People tried to peek through a little crack in the curtains to see her, some zooming in as far as possible with their phones and airdropping the pictures to as many people in the room as possible.

The Harris disconnect

It was a fitting visual — peering through a curtain — to describe my own feelings about Harris. Honestly, I’m indifferent to her. Most of her policies don’t sit well with me, but it’s more than that. The VP, along with former president Obama, come from a world that not every Black person has access to. They were both educated at elite institutions and now have more than a little bit of money in their pockets.

With all the talk about the young Black male vote veering towards Donald Trump, I think that this disconnect is a big part of it. All they know is that Trump’s name was on the stimulus checks sent out during Covid and it was tangible money that they could use.

While I don’t share a positive opinion of Trump, as a young Black woman I can empathize with the ambivalence towards electoral politics — and the mainstream journalism that often surrounds it — in general. I go home to an apartment that I share with two other people (and I’m lucky it’s just two in this economy): one of my closest friends is literally facing homelessness, another one is depressed and crushed by the weight of student debt, and then there’s my boyfriend with a huge gash on his arm, which has not been checked out because he has no health insurance.

Why should I go and give validity to this lady’s campaign — or any candidate’s? — when I know that tomorrow, next week, even next September, me and all the other people I mentioned will still be facing these issues. In summary, what’s the point?

It was a fitting visual — peering through a curtain — to describe my own feelings about Harris. Honestly, I’m indifferent to her. Most of her policies don’t sit well with me, but it’s more than that. The VP, along with former president Obama, come from a world that not every Black person has access to.

I almost didn’t go. In order to be there, I had to miss out on a class where we were focused on community journalism. We’ve been working on a project asking people in North Philly about their opinions of how journalism should function. Real work. I felt like I had bailed on my community to go to some uppity press event where I wouldn’t even get the chance to speak to the vice president. How was I helping my city, or the public interest, by being there?

After the conversation kicked off, I stepped out of the room and snuck a glance of the vice president. To my surprise, Harris didn’t appear larger than life. She was regular size, small even.

At times, I felt uncomfortable being there. It didn’t feel like I was attending this event as a journalist, but rather as a citizen — especially without a green wristband. Most of us in the conference room were students. Most of the working professionals were in the other room. Though we all wished we could trade places — not so much for the pageantry of this event, but more simply because we all want to be gainfully employed as journalists — this division didn’t sit well with me. It reinforced an idea that I see pervading our society, which is that those who’re not earning money aren’t valued.

And yet there was something restorative about the event as well. I was glad to know that in a room full of Black people, Black professionals, I wasn’t the only one who had conflicting feelings about being there or showed skepticism of the candidate. I think the questions that were asked definitely reflected that.

No softballs for this candidate

When Trump made headlines earlier this summer during his own appearance in front of NABJ members, he stated afterwards that he felt like he was unfairly attacked in the questions that he received. So, I think the eyes of the country, and even the world, were watching to see if NABJ showed any favoritism towards Harris. It was immediately clear that the vice president would not receive any gimmes or softballs.

On stage, there was VP Harris and the three moderators: Tonya Mosley from NPR, Gerren Keith Gaynor from theGrio, and Eugene Daniels from Politico.

My overall observation of Harris was that she still had “debate brain” — which is to say she was speaking to a national audience, despite the local focus of many of the questions. One example came in response to a question from moderator and WHYY Fresh Air co-host Tonya Mosley. Mosley asked if the candidate supported gun regulation that could deter violence in a city like Philadelphia, where most of the shootings are done using handguns. Harris replied by emphasizing the “need [for] an assault weapon’s ban.” When Mosley pressed the candidate, Harris gave a rambling answer that repeated common talking points, like the need for universal background checks.

I asked Mosley about the exchange later during an interview. “I don’t think she really answered my question,” she said.

Harris continued to give vague answers — seemingly appealing to voters on a national level, rather than the journalists in the room — for most of her performance. But in Philadelphia I don’t think that was enough. I think her campaign did her a disservice by allowing her to do this conversation in the major city of a swing state this close to the election and should have prepped her better on local issues.

In a few moments, Harris seemed to deploy her “Blaccent” in what I assumed was a bid to come across as relatable in the room. Her attempts at code-switching mostly fell flat. When asked about the claims her opponent had made about Haitian-Americans, her voice shifted, as she invoked a memory of going to picture day as a little girl. This happened a few times throughout the event. In a room full of Black professionals whose entire job it is to be objective, she seemed to get nothing in response. Some of us behind the curtain even cringed.

If I had gotten the chance to ask her something it would have been:

-

- How will you change the living conditions of those people who are falling off the middle class, in a material way?

- How will you ensure that people, if not covered by their jobs, have insurance?

- That if you don’t have a job a year after finishing college you won’t be punished financially?

- That housing, like water and food, is a guaranteed right because nobody asked to be here?

- How will you, as president, make sure that these things happen at a federal level and hold states and cities accountable for it?

I don’t regret going. Although I was disappointed that I didn’t get to sit in the same room as her — “to tell my grandkids” sort of thing — I did get to sit in the room with other Black people who may have had the same reservations about VP Harris. Or at least, other Black people that weren’t afraid to speak truth to power. Even if the candidate remained unknowable to me, the rest of the folks in the room did not.

Most of the media in the U.S. can make it seem as though politics only exist in a partisan binary. But last Tuesday reaffirmed that I am not the only journalist unafraid to explore the nuances and harbor serious reservations about people even if they look like me. That was incredibly valuable.

Deesarine Ballayan is a graduate student in Temple University’s Masters in Journalism program and a freelance journalist.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who represent that it is their own work and their own opinion based on true facts that they know firsthand.