While Green Bay and Philadelphia have reasonably similar median home values and family incomes, the common ground between our two cities just might end there. Green Bay is, of course, much smaller, with a total population of just over 100,000. And it’s also much whiter, with nearly 8 of every 10 residents self-identifying as Caucasian. According to Professor Richardson Dilworth of Drexel’s Center for Public Policy, the city of Green Bay’s record on race—like the state of Wisconsin’s—is instructive when compared to the melting pot that is Philadelphia.

“Like Seattle, Green Bay offers us the opportunity to see how other places do race so badly,” says Dilworth. “Green Bay is slightly less white than Wisconsin overall, 78 percent versus 86 percent statewide. But Green Bay is far less black than Wisconsin—the state is roughly 6 percent black, but Green Bay is only 3.5 percent black. This is compared to 43 percent black in Philadelphia and 11 percent black in Pennsylvania, which is close to the national percentage. The racial disparities become more intriguing when we also learn that Wisconsin has the highest percentage of any state of its black residents in state prisons—about 13 percent.”

So what does this mean? According to Dilworth, cities in which the races don’t try to live together have little to offer us as instruction. “Congratulations Wisconsin and Green Bay,” he says. “Either black people in your state and city are just more likely to be criminals, or you have a more discriminatory criminal justice system. I’m guessing the latter.”

The other striking fact about Green Bay these days is that the city’s surrounding county, Brown, went heavily for Donald Trump in the recent election. Green Bay does not have mayoral term limits and currently has its longest serving mayor, Republican Jim Schmitt, who was first elected in 2003. Shortly after Schmitt’s most recent reelection, he pleaded guilty to three charges of campaign finance fraud (in a plea deal the charges were reduced to misdemeanors). Schmitt apparently has no plans to resign, despite some calls to do so from City Council.

“I’m not sure what all is going on there, but I think all of this suggests that Philadelphia wins on a few other points,” says Dilworth. “We are not as racist as Wisconsin, we have the good sense to put term limits on our mayor, and, by comparison, we also have decent campaign finance laws.”

Green Bay Idea to Steal: Public Ownership of a Pro Sports Team

Okay, so this isn’t really an idea we can steal, since the NFL in 1960, like many other pro sports leagues, outlawed public ownership of franchises. I play for one of the most socially-conscious franchises in pro sports—I’m particularly proud of how the Eagles have led the way in sustainability—but the fact that the Packers are owned by their fans is arguably the coolest thing in sports, which makes it worth touching on here.

Here’s the history and how it works. Back in 1923, the Packers were about to fold before the franchise was saved by selling shares to the community and becoming a nonprofit. The team’s bylaws state that the Packers are “a community project, intended to promote community welfare.” Green Bay is professional sports’ smallest city, but its football team has over 300,000 shareholders owning more than five million shares. Packers stockholders receive no dividends or even free tickets. They can’t sell their shares, though they can bequeath them. And they’re limited to no more than 200,000 shares, so no one individual can take over control of the team. (The last public offering, in 2011, was for $250 per share, raising $64 million to upgrade iconic Lambeau Field.)

So what do shareholders get? They get a certificate that says they’re a part owner of their beloved football team. They get to attend an annual shareholders meeting at Lambeau Field and they get to vote on a Board of Directors and a seven-member executive committee to represent the team at league meetings. They have access to an online pro shop reserved for owners; when the Packers have won the Super Bowl, shareholders have had the opportunity to purchase Super Bowl rings, though a cheaper version than those given to the players.

But what shareholders really get is the psychic reward of being part of a treasured public trust. Packers’ profits are re-invested into the franchise and the city of Green Bay. 60 percent of the team’s concession stand sales are donated to local charities. It’s a true community; when Lambeau Field needs shoveling after a snowstorm, a call for volunteers goes out and an army of volunteers pitches in.

In 1960, the NFL adopted bylaws that barred any future team from being a nonprofit, community owned entity. So we’re left with the Packers, and the team’s unique relationship with its fans, proving year in and year out that competing on the field and public ownership needn’t necessarily be mutually exclusive.

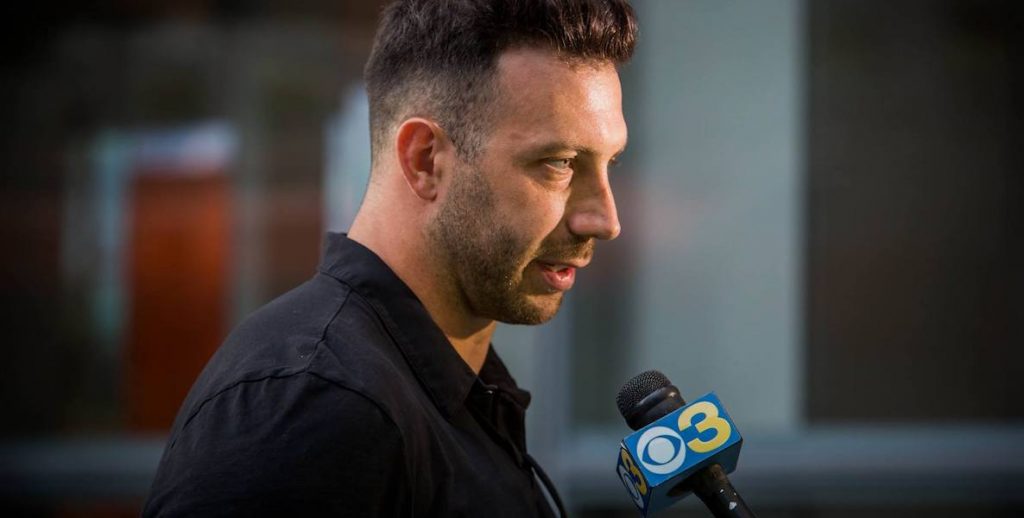

Connor Barwin is the Eagles defensive end and runs the Make the World Better foundation, which works to refurbish city parks.