![]()

In 1888, the secret ballot seemed like a good idea. By the 19th century, the voting process had become a rough business. It was a public affair—a mix of carnival, marketplace, celebration, social gathering and auction block where votes could be bought and sold.

The voter and the crowd

After slipping through the crowd, perhaps avoiding a thug or two, the voter arrived with a colored ballot, courtesy of a political party, deposited it in the ballot box for all to see, and then joined the cluster of voters and bystanders to drink, dance, watch and debate the virtues of one candidate over another.

The turnout was high—as high as 82 percent in 1878. Like any community event, it was a time to see and be seen, to feel that on one day, at least, “everyone” was a part of the political process.

But there was discontent among the political class. Progressives argued that people should be able to vote in private to shield them from bullies and bribes.

Conservatives worried that the “wrong sort of people”—the poor, the immigrant, the freed slave, the illiterate—were tipping the government in the direction of 19th-century liberalism.

It seemed time for a reform. And reform they did—literacy tests, poll taxes and the registration process itself. Each, a barrier. Still, the turnout remained high.

![]()

No wonder turnout dropped from 82 percent to 50 percent, where it has remained. The United States is now near the bottom of the list of democratic countries in terms of voter turnout, 26th out of 32.

This loss of “social identity” was important. It is what bonds us and is the source of our personal pride and identity. It is reflected in our rallies and protest marches. It is why we proudly say “We are Americans” or why we root for our hometown team and wear its jerseys.

When voting became secret, we lost a space to proclaim our civic identity and display our social duty.

A solution for the 21st century

We should not return to the 19th century voting marketplace. But if we wish to increase voter participation and civic engagement, we must rediscover ways to recreate a civic stage, to make the community of voters more visible.

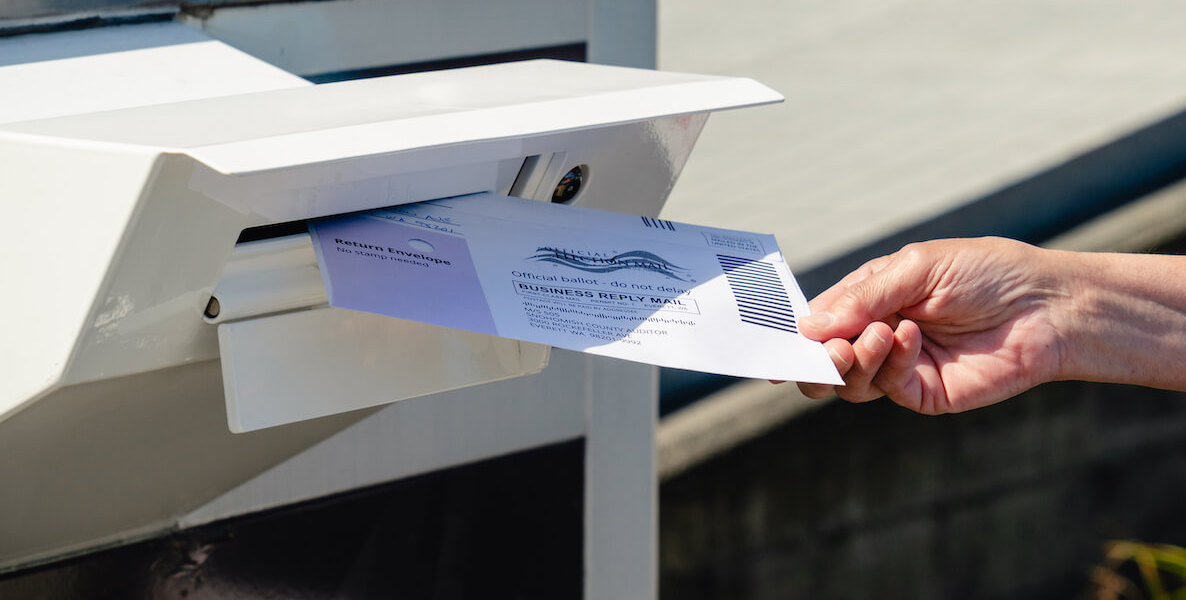

Now being considered is a host of reforms, many with the laudable intent of getting more people to vote. But each of them—mail-in ballots, online voting, early voting, and automatic registration—will make the act of voting less visible and go further in dismantling the civic stage.

Getting on the civic stage

If we want to rebuild a public space that includes “the voter,” we might look to a few approaches.

- We could make public the names of those who vote—not whom they voted for. It is time to give recognition to the voter. In a democracy, the voter is (or should be) the most important actor.

- We could make voting a competition—not the competition for office but the competition among communities to see which has the highest percentage of voters: the “winning community to receive a cash prize in support of its schools, parks or some other civic priority. The community that works together for a common goal asserts its pride of collective strength.

- We could make voting a team sport with members wearing team colors—in this case, a badge or a sweatshirt proclaiming “I am a voter” worn in the month prior to the election. There’s pleasure, excitement and passion when we see “our team” and the fans together.

It is time to rebuild the civic stage and then step onto it.

Neil Kleinman is professor (emeritus) of innovation and entrepreneurship at the University of the Arts, where he was director of the Corzo Center for the Creative Economy and dean of the College of Media and Communication. He is also a lawyer and co-founder of the BroadSide Collective LLC., a social impact group. For those interested, the Collective offers free downloadable tag lines to add to email addresses, a Zoom backdrop, and formats for Window/Car Cards or Posters here.

It’s election season in Philadelphia. Are you all set to vote?