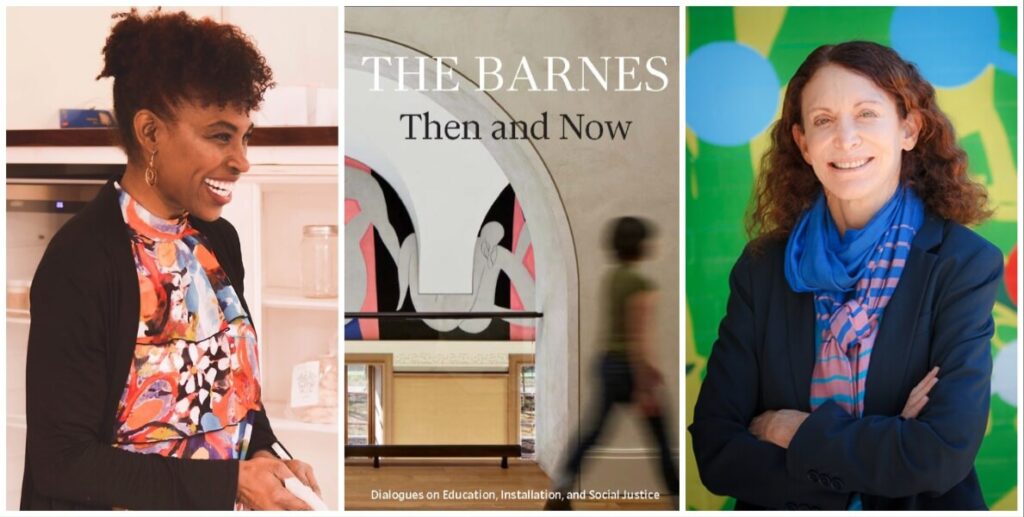

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from “Conversation: Reflections on Art and Social Justice,” originally published in The Barnes Then and Now: Dialogues on Education, Installation, and Social Justice, edited by Martha Lucy.]

The modern notion of social justice emerged in the early 19th century, when the rise of capitalist modes of production created unprecedented inequities for the industrial working class. While Albert Barnes probably never used the term — it didn’t enter common usage until the later 20th century — the idea of a more equal distribution of opportunities within society was a central motivation for establishing the Barnes Foundation. Writing in 1925, he described his endeavor as an educational space for “the plain people, that is, men and women who gain their livelihood by daily toil in shops, factories, schools, stores.”

If Dr. Barnes’ idea of social justice hinged on education for the working classes, he was also attuned to the glaring problems of racial inequality in the United States. Railing against the evils of racism, but optimistic about the future of Black art and culture, he wrote that the country’s “unjust oppression has been powerless to prevent the black man from realizing … the expression of his own rare gifts.” He took steps to support this expression, providing educational scholarships for Black writers, artists, and musicians. And yet Dr. Barnes’ progressivism had its limits. With the exception of Horace Pippin, he did not collect the work of Black American artists, reasoning that a fully evolved African American art was still decades away.

“Close your eyes and think of Philly without 4,000 murals, without public sculpture, without arts institutions, without theater, without music, without spoken word, without writers. It starts to become a vision that is pretty bleak. Art enriches our lives.” — Jane Golden

Social justice continues to be central to the Barnes mission. The institution is committed to exhibiting the work of women and people of color; free programs engage children from underserved communities; and a new restorative justice program enables incarcerated people to create and exhibit art. But how effective are these efforts? Given the monumental problems pressing on the world today, can we really hope to address societal inequities through art and art education? Can art actually transform communities and shape public policy? How does this happen?

The participants in the following dialogue, held at the Barnes in September 2022 — Jane Golden, Mural Arts Philadelphia founder and director; and Valerie Gay, deputy director for audience engagement & chief experience officer at the Barnes — firmly believe in the potential of the arts, and in the responsibility of public arts organizations, to help build a more just society.

Roxanne Patel Shepelavy: Valerie, could you give us a little bit of background on Dr. Barnes and social justice — or whatever his version of that was?

Valerie Gay: First, imagine it’s 1908 and Dr. Barnes is in his West Philadelphia factory at 40th and Filbert. It was a small factory, with about 20 folks or so. But he hired Black men and White women to work in the same place, which was progressive for that time, especially when there were parts of the country where it would have been illegal. It was a real act of defiance.

Second, Philadelphia is a working-class town. Anyone who has been here any period of time knows that we have our educators and doctors but are, at our core, a blue-collar town with lots of factories. Imagine a factory at a time when the labor movement was just getting started. You had an employer who paid a living wage for eight hours a day, but whose employees only worked six hours and spent two hours discussing art, looking at art, and discussing philosophy.

It gets better, because Dr. Barnes actually disaggregated intelligence from education. It’s 1908, I’m Dr. Barnes, and you’re a Black man in Philadelphia working in my factory. I’m going to make a couple of assumptions about you. I’m going to assume that you are undereducated. But do you know what? You’re off the hook because you have a brain; you can think. Mary Mullen, whom I have hired as my first instructor, will read to you. You may be illiterate, but you still have a brain and a tongue, so you can tell Mary what you think about what she just read. That is progressive, right?

Those acts inspire me to think about the 21st century. To me, many of the things that we’re doing today, particularly as they revolve around social justice, go back to those roots.

What’s great is that [the Barnes is] basically doing the same thing now — talking about art with all sorts of different people. Jane, let me ask you about the history of the relationship between Mural Arts and the Barnes and how you see your missions aligned.

Jane Golden: It’s really interesting because this is the site of the former Youth Study Center [a juvenile detention facility]. When John Street was mayor [2000-2008], it was pretty life-changing because we were made part of the Division of Social Services. We started working right away in prisons with the Department of Behavioral Health, and we started working at the Youth Study Center. It was a terrible place, but we tried to bring beauty and whatever hope we could. We loved the young people tremendously.

About that same time, we started working in prisons.This name kept coming up — [Barnes Director of Adult Education] Bill Perthes. Bill was talking to the men about art and about ways of looking at art — and, by extension, ways of looking at life and at themselves in relationship to art. They had a deep and profound love of art, and so much talent.

“There is a plethora of talent in this city, and yet we don’t value it the way we should. The way we start changing that is we start valuing it.” — Jane Golden

We ended up connecting with Bill, and it was surprising to be invited to work with an institution like the Barnes, because for so long when I worked for the Anti-Graffiti Network, in the early years of Mural Arts, many of the “high-art” people in the city didn’t value the work. I’ve spent a lot of years trying to understand that and unpack it, but over and over, people would say, “You’re not really doing public art.” I would say, “Well, we’re in public doing art, so if we’re not doing public art, what exactly are we doing?”

Being invited to work with the Barnes was a thrilling experience that our restorative justice program could be rooted here, that we could eventually have a show here, that we could do projects and programming here. I can’t begin to tell you how important it is when a large institution like this, with its power and its cachet and the art, is using its power for good. And to partner with us, a community-based public art program — you opened the doors to us in a way that was so extraordinarily meaningful and lasting.

We’ve done lots of different things with the Barnes, but the social justice work, the restorative justice partnership, I think, is really deep and wonderful.

Valerie, you came most recently from Art Sanctuary, which is an organization that celebrates Black art as a way of building communities and transforming lives. What are you doing at the Barnes that continues that work?

VG: What I learned at Art Sanctuary is that art is essential to the human condition. When you talk about communities of color, when you talk about lower socioeconomic communities, when you talk about any kind of marginalization, art is often stripped from external resources. But at the same time, art cannot be repressed, so it continues to bubble up.

What we see in our world is that, in communities that have been disinvested, there is so much creativity, there is so much art happening.

In 2006, when I was a member of the Leadership Philadelphia class [a program that trains and mobilizes professionals to serve the city], Jane Golden came to our culminating ceremonies to speak. One of the things that I loved was a story about the Anti-Graffiti Network. This group of artists showed up at her door. They had art books that they had stolen from the library, and they said, “Hey, can you show us how to do this?” Because they’d been doing it already on the walls, but their technique might have been off, right? They really wanted to learn. It’s like you can’t hold art down.

I often say to people — particularly folks who don’t feel like they belong here or in any of our other amazing art resources that we take for granted — first of all, it does belong to you. And, second, when you see the people in your life expressing themselves, particularly children with crayons — if they happen to write on your wall, don’t scold them. Give them some paper. Give them some space. Get some chalkboard paint or dry-erase paint and let them express themselves, just like those young men who came to Jane and said, “Show us how to do it.”

Five or six years ago, we started the Community Engagement and Family Programs. We have a great partnership in West Philadelphia with the People’s Emergency Center. What happens if we partner with organizations that are not technically arts organizations? We come together as equal partners and bring folks together. We go to where people are. We work hard to develop relationships and to be good guests in people’s homes. We make art with them. We have performances with them. And then we bring them to our home [the Barnes], and they feel like this is their home.

We also have a program with Puentes de Salud called Puentes a las Artes. This program is now five years old, so our alumni are in second and third grade. The world opens up to them both from a language perspective and because they believe that the Barnes is theirs. When they come here, they feel at home. Once a month, we bring families in. On some Sundays, the tours are offered in Spanish, as part of Puentes a las Artes. The first hour, we study a particular artist. Then we bring them down to our Keane Family Classroom. While the children are making art based on the themes that we just studied, the parents and guardians go into the seminar room and talk about things like parenting skills and how to navigate the public transportation system.

We also have a virtual reality program in partnership with the [Free Library of Philadelphia], the Department of Parks and Recreation, senior centers, organizations all around the city. Unlike many of the virtual reality goggles that you see now, they don’t strap on your head; they are meant to be social. You hold it up to your face, and you see the entire Barnes collection. Someone we call our Community Connector guides you, answering questions, and then we invite the participants here.

I should say that the virtual images are flat and the colors are not right. But to the participants, they look amazing.The goggles are not meant to replicate the experience of being in the Barnes. They are meant to eradicate the barriers to entering the Barnes. To a person, what we have seen is people walk into the first room here, and there are gasps: “Oh, my gosh, did you see that?”

We also work [across Philadelphia] with toddlers in partnership with other organizations, as well as at summer camps through Parks and Recreation. In all of the programs, we give folks what we call our Community Pass, which is a Barnes membership for community members. Whoever is holding the pass can bring up to three people for an unlimited number of visits for up to a year. They get the same discounts that we, as staff, get in our shop as well as in our restaurant and our food kiosk, and they know that they are welcome. I am so grateful to work in a place where we all recognize that we are not cannibalizing our membership program. What we are doing is expanding our audience and expanding our membership program.

Right before Covid, we were talking about scholarships, because what we are is an educational institution that happens to have this amazing collection. What would it look like if someone who has never been to the Barnes encounters us through one of these programs in their community? Then they come into the Barnes, and we tell them that they could learn more about this.

Pre-pandemic, we had a very limited number of scholarships. But with the technology available to us now, there has been an exponential increase in the number of people who have been able to participate at every level. I am grateful that it’s not just my department — it takes the entire institution to right ourselves toward [something] that we actually believe: just as art ignites change, art is for all.

When we talk about social justice, we talk about how people live, thrive, raise families, stay healthy and safe. In the midst of all those incredibly concrete needs, how do you talk about why it is we should care about art?

JG: Art humanizes us. Close your eyes and think of Philly without 4,000 murals, without public sculpture, without arts institutions, without theater, without music, without spoken word, without writers. It starts to become a vision that is pretty bleak. Art enriches our lives.

But I am a very practical person, and so at Mural Arts we’re both aspirational and highly pragmatic.

What we see in our reentry program is phenomenal. We have a recidivism rate that hovers between 8 and 10 percent. The national average is 65 percent. We can have all these reentry programs where people are picking up litter, or, we can provide people with meaning. We can help people uncover the genius that lies within.

Creativity … flourishes. It’s like a wildflower that grows in a vacant lot. Art becomes a tool. Art becomes a way of building resilience and grit. We think about our intractable problems, and there are traditional ways of dealing with them. What astounds me is they often fail us, and then we do it again and again and again. So our ability as a society to hold on to creativity, innovations, artistic thinking, having artists at the table, to think differently, to think out of the box is absolutely 100 percent critical. Because when we do that, something moves, something changes. In our behavioral health program, Porch Light, we work with people struggling with housing insecurity, substance abuse, deep trauma. We work in immigrant communities; we work with veterans struggling with PTSD — all of it.

“One of the ways to change the world is to start where you are.” — Valerie Gay

Yesterday, I was in Kensington, where we have a Color Me Back program, a same-day work program. In Albuquerque, in Detroit, in Phoenix, they have same-day work programs where people are picking up litter or cleaning alleys. Can’t we dignify the human experience by providing people with beauty and opportunity and the ability to make their mark on our city in a big, bold, wonderful way? [I was] standing with 100 people who were cheering art, most of whom had never had any experience with art but now feel like they are artists. And they are. We’ve created pathways so people can go from working part-time to working more hours, to being an assistant teaching artist, a teaching artist, an assistant muralist, a public artist, so that this isn’t just a flash in the pan for them.

In Art Education, we have 2,200 kids ranging in age from 11 to 18. For them, it’s tapping into their imagination, challenging them, teamwork, leadership — letting them know they can have an idea and they can bring it to fruition. At the Barnes you’re providing food for the soul, so when kids walk in here, [they know] that that could be them. [Art] enriches their lives; it opens them up in ways that are endless.

We’ve had projects that are incredibly contentious, where in the beginning [you feel that] this is never going to work. This ship is sinking. And somehow, the art is able to pull people together and inspire people to acknowledge and recognize that it shines a light on diversity and difference, but it underscores a commonality. So that through line is a strong, connecting force that we need today in our world.

VG: Absolutely. It transcends everything. I often say that my job is to ensure that every physical being that comes into this building feels welcome, that they belong here, that there is a connection between their lived experience and the art that’s on the walls — which is a tall order since we’re not all represented fully on the walls or in the objects.

But there is something about the humanity that comes out of that art that connects. I’ve seen young people, I’ve seen families who have never been in the Barnes before saying, “Oh! Look how she’s holding her daughter. That reminds me of how my mom held me.” Or “That reminds me of my grandmother.” Or “That reminds me of my neighbor.” We can transcend. We see the differences. We celebrate the differences. We’re not trying to eliminate the differences, but we see the commonalities too, and art can bring us together.

What responsibility do museums have to the communities in which they are situated or to which they are adjacent?

VG: We ask ourselves that question everyday, frankly. Right before the pandemic, we merged our frontline visitor services with our out-sourced security team. You may have noticed that if you come into the Barnes, you don’t see people in guard uniforms. And it’s not just about the clothing that they wear. The core of [this change] goes all the way back to the beginning of the foundation and Dr. Barnes’s educating his staff. What would happen if we took the folks who may be the least skilled, the lowest paid, at the entry level, and we provided them an opportunity to see the museum world in a way that they may have never seen before?

We created a program called Pathways. It took us a while to do it. We had to keep reaffirming that what we were doing was actually what we said we wanted to do and that everyone was on the same page, from our board to our staff. We are training the current and next generation of museum workers. We are diversifying our community from the inside out.

About seven years ago, I read that the Whitest career in the United States is the museum curator. Frankly, one could say that all museum workers are not too far behind, if you go beyond the frontline staff. Imagine we say to someone, What are you interested in? We surveyed, and all the parts of the institution came up. We have people who are interested in these things; now we have to find other people who want to help train them. We have a stellar internship program.

Stephanie Stern, who runs our internship program, helped oversee the making of a competitive internal internship program. Staff apply to [participate in] 12- to 16-week projects that we create for our colleagues. They can walk away with something for their portfolio.

They could also walk away saying, “I never want to see that thing again!” We’ve had people move up, and we’ve had people move on.

One of the ways to change the world is to start where you are.

I believe that’s what we’re doing. It’s not one person. All of us together are partners in this. And we cheer when members of our front-line staff have been elevated to areas that they never thought they would be able to reach.

JG: I think the Barnes is a good example of a museum that is very aware of its responsibility in the city, so that the borders are more porous. At the Anti-Graffiti Network, it was interesting to see so much raw talent and work with so many young people who didn’t have opportunities. We started a program where we would come to the [Philadelphia Museum of Art] on Saturdays, and everybody got to pick the collection they wanted to see. Then we started having these fabulous artists like Richard Watts, Charles Searles, and James Dupree, who would meet us there, and they would show us their favorite collection. The museum became a sort of home, and the kids would say, “Jane, this is just like out of the movie Rocky” — that was their whole relationship with it. It [had been] like this house on a hill that was completely detached.

I realized that it didn’t have to be that way. The question then is how does a museum do its work with real integrity, so it’s not just a few four-week classes — that it’s year-round, that there is this broader commitment. How is there an acknowledgment of the arts ecosystem in our city and what we want? The outdoor museum and all those artists and all the artmaking that goes on shouldn’t be separate from an institution like this.

I will say this again and again and again: I think that we’re behind.

As the fifth-largest city in the country, we’re behind. We have to acknowledge that the cultural organizations in our city are world-class. There is a plethora of talent in this city, and yet we don’t value it the way we should. The way we start changing that is we start valuing it.

We all start doing it.

The challenge, for all of us, is to ask ourselves what it is we believe in and then do our best to act on the beliefs that we have, because the world that we create today is the one that we pass on. What do we want for our city? There is strength in numbers and collaboration and creativity.

Excerpt from “Conversation: Reflections on Art and Social Justice,” originally published in The Barnes Then and Now: Dialogues on Education, Installation, and Social Justice, edited by Martha Lucy, © 2023 The Barnes Foundation.