In his final State of the Union address last month, President Obama singled out gerrymandering as a necessary reform to restore the public trust in our government institutions. “We have to end the practice of drawing our Congressional districts so that politicians can pick their voters and not the other way around,” he said.

Those who are steeped in the more nuanced details of politics know all too well the phenomenon of gerrymandering. Those who were tuning in for their first ever State of the Union probably had no idea what President Obama was talking about (if they weren’t too busy trying to find “Jerry Mander” on their bingo cards or drinking game list). Either way, this seems a good opportunity to consider the issue, and what it means for us here in Philadelphia.

Ok, get to it already. What is gerrymandering?

Every 10 years, after the U.S. Census comes out, we need to redraw political boundaries to ensure that each district has equal population. These districts come in all shapes and sizes: U.S. House districts, state House and Senate districts, City Council districts, and more.

Legislative bodies get to redraw their own districts. Typically, the majority party will have control over what the new districts look like. If you smell an opportunity for corruption, then congratulations, you get a gold star! Unfortunately, you also get political corruption.

“Gerrymandering” is when districts are redrawn deliberately to give an electoral advantage to one party over the other. The goal of the gerrymanderer is to draw districts that are skewed in favor of his or her own party.

Pennsylvania is a great (ok, terrible) example of gerrymandering. In 2014, there were about 4 million registered Democrats and about 3 million registered Republicans. You would expect, then, that Democrats would have a majority in the state House of Representatives. If all held according to averages, the state House should have something like 116 Democrats and 87 Republicans. But, thanks to gerrymandering, it’s practically flipped, with only 84 Democrats and 119 Republicans.

Why is it called “gerrymandering”? That’s a pretty ridiculous name.

It’s named after a salamander. No, really! In 1812, the Governor of Massachusetts, Elbridge Gerry, signed a bill that redistricted state senate seats favorable to his confusingly-named Democratic-Republican party. One of the districts was likened to a salamander, and the word “Gerrymander” was born.

How does it work?

There are two main strategies in gerrymandering: vote splitting and vote packing. In vote splitting, the goal is to divide the opposition’s votes so that they never have enough for a majority in a district. In the image below, example 2 (third from the left) shows how splitting the vote leaves a 40 percent minority with zero representation. This is typically employed by the party with more voters. For instance, in Philadelphia, there is only one Republican district Councilperson compared with nine Democrats. If the Democrats took gerrymandering to an extreme, they could split up the Republicans in that one district and scatter them among the other nine. If successful, they could obtain a Democratic majority in every district, further marginalizing Republicans.

Why is gerrymandering a bad thing?

It’s only a bad thing if you’re the one being disenfranchised! Pennsylvania Republicans probably think gerrymandering is a pretty sweet deal, and Democrats in other states enjoy similar advantages.

In all seriousness, gerrymandering bastardizes the very notion of representative democracy. It’s not okay to game the system so that the minority rules the majority. It wasn’t okay when voting was limited to white male property owners, and it’s not okay when it’s done with gerrymandering.

It also contributes to political gridlock. According to Patrick Christmas, Senior Policy Analyst at the Committee of Seventy, gerrymandering “heightens the importance of primaries and diminishes competitiveness in general elections. Districts made safe for one party or the other amplify the influence of primary voters, who may lean farther left or right than the overall electorate.” And it’s a vicious cycle: “Pushing candidates towards primary voters skews them towards the fringes,” he says, “which makes compromise difficult because they’re worried about those primary voters for reelection.”

Is Gerrymandering a problem in Philadelphia?

Yes. And to make matters worse, both parties are responsible, just at different levels of government.

At the state level, Pennsylvania is one of the worst-gerrymandered states in the Union. The party being disenfranchised is the Democratic Party, and Philadelphia is overwhelmingly Democratic. So, essentially, the state districts are gerrymandered specifically to screw over Philadelphians. Here’s what Philadelphia’s state House districts look like:

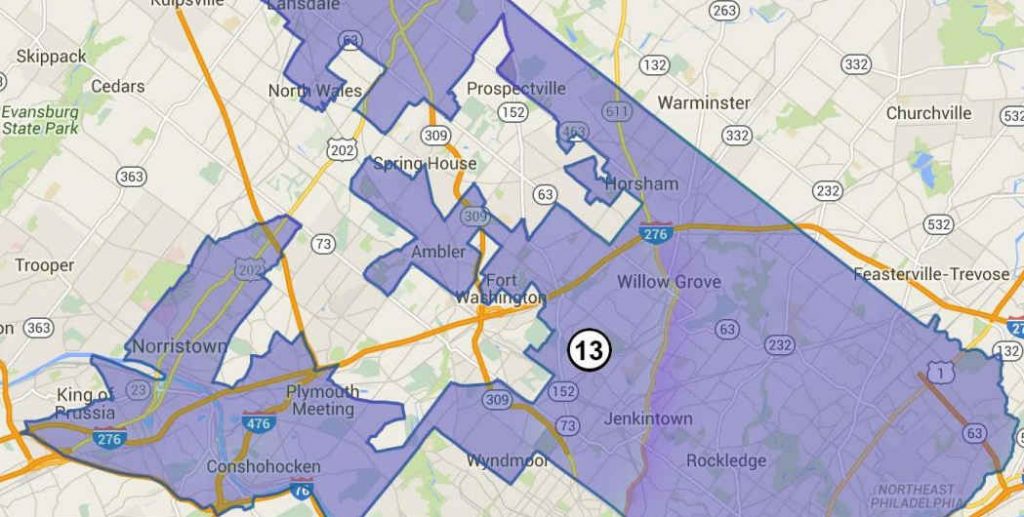

Philadelphia gets gerrymandered at the national level as well. Our three Congressional districts (PA-1, PA-2, and PA-13) look like this:

But Republicans aren’t the only bad guys here! Take a look at our City Council districts, which are drawn by Democrats. This is what we currently have:

Look at that weird appendage on the bottom of the 3rd District, and the outstretched right arm on the 5th. The sad thing is, this was a whole lot worse prior to the current census:

If you can make sense of that 7th District (which snakes its way up between the 6th and 10th districts), then you’re either a hero or on some pretty good drugs.

According to Christmas, most of the gerrymandering of Council districts is done not to empower parties, but to build strategic coalitions of wards and political power players. “Differences in party registration aren’t a huge factor outside the lower-northeast,” he says. “Some wards have more influence and higher turnout, and a lot of it comes down to where certain politicians’ friends and allies live.”

Why is gerrymandering allowed to exist?

The legislatures get to make their own rules on this. That’s democracy for you!

Oh, right, “checks and balances.” That’s supposed to be a thing, wherein either the executive branch or the courts keep the legislature from doing something so undemocratic. This would normally fall to the courts, since they would be the ones to judge whether or not a redistricting scheme is fair. Unfortunately, courts almost always defer to the legislature on this type of issue, calling it a “political question”: Essentially, courts say that these types of problems aren’t proper for them to decide since they boil down to political disputes, not legal disputes.

In Pennsylvania, oddly enough, the state Supreme Court holds the cards. Redistricting is handled by a five-member committee. One member comes from each of the House majority party, House minority party, Senate majority party, and Senate minority party. That means 2 Republicans and one Democrat. The fifth member is selected among the Supreme Court Justices. Essentially, the party that controls the Court controls redistricting—which is one reason why the recent sweep by Democrats in the November election was such a big deal.

Are there better ways to draw districts that avoid political bias?

The better question would be, are there worse ways to draw districts than the way we currently do it? (Answer: No.) But redistricting is still a tough task.

The only rule that legislators must follow in redistricting, as handed down by the Supreme Court, is that of “one person, one vote.” It used to be that various legislative districts could have incredible disparities in population: one might have 10,000 people and another might have 100,000. In 1964, the Court ended that practice. Now, all districts have to be roughly the same size.

An alternative to allowing legislatures to redraw districts is to appoint independent commissions to do the work. But independent commissions have to be run by humans who, like legislators they’re appointed by, are susceptible to bias (and being bought off).

Fortunately, there is a better way. Algorithmic redistricting focuses on a second rule in addition to “one person, one vote”: compactness. Compactness basically measures how ridiculous a district looks. The closer a district is to looking like a circle, the more compact it is, and therefore the less likely it is to be biased. The less it looks like a circle, the more we should be wary of gerrymandering. Not every district can look like a circle, but no district should look like a salamander. The only data used by algorithmic redistricting are population and location; there’s literally no other information, so that the results can’t be biased by anything.

What would districts look like without gerrymandering?

There are different approaches to automated redistricting, but they all tend to get to roughly the same results. The following are a few examples.

For Philadelphia, Azavea Atlas held a competition to redraw districts during the last go-round. The current districts turned out quite differently:

Below are more examples of hypothetical redistricting using unbiased methods:

Pennsylvania House of Representatives:

Pennsylvania Senate:

Pennsylvania’s U.S. Congressional districts:

All U.S. Congressional Districts: