If you haven’t heard by now, there’s a mini-progressive revolution afoot in Philadelphia. Because we are, effectively, Moscow on the Delaware—long a corrupt one-party town, in which Ds outnumber Rs by an astounding 8 to 1 ratio—we’ve reserved two seats since 1952 on City Council for non-Democrats. Those seats have been held by Republicans, the party that—in cynical exchange for the crumbs of patronage—long ago ceased to truly compete politically.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

![]()

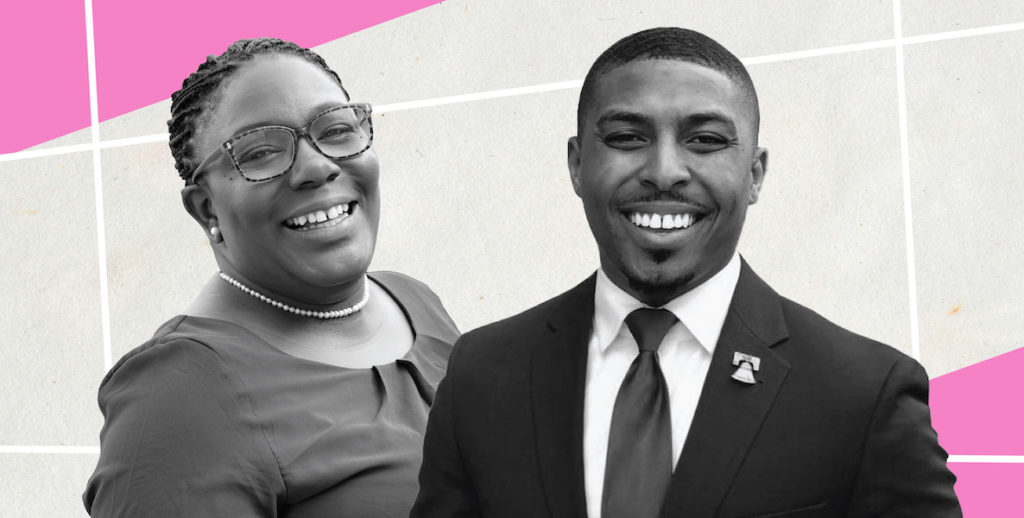

Pastor Nicolas O’Rourke took in $88,000 and Kendra Brooks nearly doubled that; both out raised incumbents Al Taubenberger and David Oh, as well as GOP challenger Dan Tinney, since June.

Moreover, the Working Families candidates have wrung up impressive endorsements. Councilwoman Helen Gym angered the Democratic establishment by endorsing community activist Brooks—thereby urging voters to effectively pull the lever against at least one of her Democratic colleagues. (Each voter gets five votes for the seven at-large seats). Even Elizabeth Warren got in on the act, endorsing Brooks the day before the national Working Families Party endorsed her presidential bid. And a host of Philly progressives have jumped on the Working Families bandwagon, among them State Reps. Elizabeth Fiedler, Chris Rabb and Malcolm Kenyatta.

Most political insiders—the keepers of conventional wisdom, which almost always turns out to be wrong at some point—say the Working Families Party candidates still face long odds in November. That may be, but clearly there is an energy behind their candidacies that the establishment ignores at its peril. All of which raises the question: Is the rise of the progressive Working Families Party here (it’s had quite a lot of electoral success in New York) a good thing for Philly? Does what they’re selling, idea-wise, fit what Philly ought to be in the market for? And, critically, will even more of a leftward local swing amount to smart politics in a purple state with a Republican legislature?

“Instead of using polarization as a technique,” Berry said, “we have to step into conversations and stay in those conversations rather than stepping in and stepping out.”

Let’s take that last question first. Two weeks ago, citing the strangely similar political stylings of Larry Krasner, Phil Murphy and Donald Trump, I wrote about the new amateurism that has come to define our politics. Officeholders abound who would rather be right than effective, who prefer the easy scoring of rhetorical points on Twitter to the harder act of moving the needle on seemingly intractable problems. When Gym endorsed Brooks—whom she’d long known and been allied with—it may have been another case study in naive politicking. Gym has rightly railed against Republicans in Harrisburg for underfunding our schools; but it’s infinitely harder to secure said funding increases from the Rs who control the state coffers if you’re explicitly trying to decimate what’s left of their party locally.

Ever-thoughtful State Representative Chris Rabb ain’t buying that argument. “I’d be surprised if my Republican colleagues in the state legislature even know we have Republicans on City Council,” Rabb, a passionate progressive, told me when I asked him to walk me through the rationale of his endorsement. “I doubt the Republicans on Council even have a relationship with the Republicans in Harrisburg, because they have no power and also because they’re too liberal. The Republicans in Harrisburg are more Tea Party-aligned.”

For Rabb, the Working Families Party endorsement was a no-brainer born mostly of ideological alignment. “I ran as a progressive, and we need more qualified progressives in public service,” he said, ticking off the list of issues he and the Working Families Party have in common— Medicare For All, a $15 minimum wage, criminal justice reform; all issues, of course, that will decidedly not be adjudicated at the city level.

Besides, Rabb argued, endorsing O’Rourke and Brooks sends a much-needed message: “Progressivism doesn’t necessarily equal white liberalism,” he said. “Here you have two qualified black progressive candidates. Liberalism no longer has to be the province of white people.”

Rabb forcefully makes the case for change, but his argument lacks grounding in the realpolitik of our local story. That’s understandable; in the age of Trump, everything, at every level, has become about the big, dividing line issues, which explains the slogan of Brooks’ candidacy: Republicans Out, Working Families In.

Brooks, in particular, has a great personal story. She was raised in Nicetown and was a teenage single mother working a low-wage job who ultimately worked her way through college and got an MBA. She became a citizen activist, leading the fight against Mastery Charter Schools—the stellar turnaround charter operator—taking over her neighborhood elementary school. But she’s not running on her biography so much as ideological talking points that could apply to Anytown, USA, complete with redistributionist jargon—as if there’s anything left in Taxadelphia to redistribute—and nods to identity empowerment.

“There is plenty of wealth in this country and this city,” Brooks writes in her questionnaire for Reclaim Philly, ground zero for local Social Democrats. “Our problem has never been if we have enough money, but instead if our elected officials have the political courage to check the powers of the 1% and to demand funding for resources for poor and working people. As a City Councilperson, my job would be to demand the 1% pay their fair share for fully-funded schools and affordable accessible housing for all, while also making sure that we pass laws that protect working people from corporations and ensure fairness and dignity at work…As a councilperson, I will always look for laws that lessen and abolish white supremacy and patriarchy in our system, and that uplift Black and Brown people, women and gender non-conforming people. To me, this starts with fully funding our education system, [and] ensuring accessible affordable housing for all people.”

Okay, so Brooks may sound like an SNL parody of progressivism, with all the right buzzwords arranged just so, but let’s stipulate that, in general, she lays out laudable goals; abolishing white supremacy and patriarchy are good things. However: How you go about achieving such goals is what politics is actually about. And ideological rigidity has always been a prescription—ironically—for perpetuating the status quo, not challenging it.

In general, Brooks lays out laudable goals; abolishing white supremacy and patriarchy are good things. However: How you go about achieving such goals is what politics is actually about. And ideological rigidity has always been a prescription—ironically—for perpetuating the status quo, not challenging it.

Brooks’ activism work bears this out. Back in 2014, she led the parents at Edward Steel Elementary in rejecting Mastery’s takeover. “Local control” was the mantra; there was much celebrating when Mastery backed out, not wanting to help where it wasn’t wanted. This despite the fact that Mastery would have brought in excess of a million dollars in privately raised grants to the school and 21 additional full-time staffers. It’s now five years later and, according to the database schooldigger.com, Steel performs academically better than only 0.8 percent of elementary schools throughout the commonwealth. What’s the point of all that activism if the kids you purport to serve are, five years on, still not getting the education they need?

This is not to question Brooks’ motives. Her intent is pure and her story is uplifting. But it is to suggest that trying to square national progressive values with local on-the-ground realities can often unintentionally double down on the same-old, same-old. Think, after all, about the many ways we distort progressivism in Philly. If you support Larry Krasner’s criminal justice reform, as I do, do you have to sign on for the dissing of victims and reduced sentences for murderers? If you support the union movement of the 20th Century for building a vibrant middle class and an economy that was the envy of the world, do you have to turn a blind eye to the thuggery and shady political dealings of Philly labor? If you support early education funding and the refurbishing of city playgrounds, do you have to be for a tax on sugary drinks that disproportionately hits poor and working class families?

The key, he once said in an interview with the Yale School of Management, is listening…and then seeking common ground, even when it’s uncomfortable. “Instead of using polarization as a technique,” the then-Mayor of Albuquerque said, unknowingly offering advice to the likes of Brooks and O’Rourke in modern-day Philly, “we have to step into conversations and stay in those conversations rather than stepping in and stepping out.”

In the coming weeks, I’ll be spotlighting local leaders who come from Berry’s political lineage. In their book The New Localism, our late chairman Jeremy Nowak and Bruce Katz famously proclaimed that “the future belongs to the problem-solvers.” Let’s scrub our fractured politics and shout out a new generation of New Localism leaders.