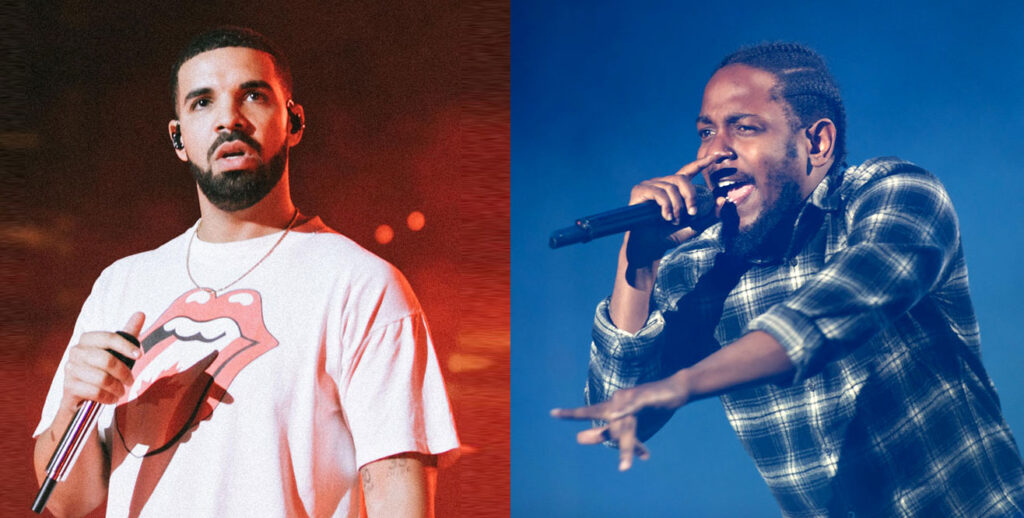

For the last few weeks, millions have obsessed over the unusually prolific war of words between rap titans Aubrey “Drake” Graham and Kendrick Lamar. Indulging in a time-honored ritual of verbal contest by releasing nine “diss” recordings between them, each rapper has lobbed serious and superficial allegations against the other, ranging from infidelity, domestic violence, sexual misconduct, and hidden children, to plastic surgery, small feet and the like. If personal reputations have been bruised a bit, business has boomed as five of the diss tracks claimed the top 12 spots on the Apple Music charts.

Fueled by social media, partisans of both wordsmiths deconstruct each new seizure of rhetoric with the zeal of literary critics parsing Shakespearean sonnets. In a way, that is the case here; in the vernacular, one “sons” or disgraces a figure by treating him like a figurative child. Thus, these exchanges are “son” nets, webs of verbiage meant to trap and discredit one’s opponent. Yet the relentless stream of grassroots commentary has drowned a vital feature of the imbroglio: it is a proxy war for looming conflicts that are far more difficult to unravel, namely, racial authenticity, colorism, democracy, the ongoing conflict of Blacks and Jews, the war in Gaza and DEI.

I.

The Drake and Lamar beef was the main course, but nine other artists, and a basketball star — including Future, Metro Boomin, A$AP Rocky, The Weeknd, Nav, Travis Scott, Rick Ross and Ja Morant — joined Kendrick in trying to stick a fork in Drake’s body of work, and in some cases, his very body. Ross, a frequent collaborator with Drake, released a diss track, “Champagne Moments,” and repeatedly termed Drake “White boy,” a reference to his mixed-race heritage.

The accusation picked up steam, and streams, on social media platforms. Drake was unceremoniously refashioned as a tribal impostor, a familial phony, a racial interloper, a bi-racial Canadian culture vulture who sucked the blood from Blackness. In some Black circles he went from Drake the GOAT (greatest of all time) to a scapegoated wannabe Black rapper. “No, you not a colleague,” Kendrick accuses him on “Not Like Us” (the title says it all), “you a…colonizer.”

The astonishing and deflating speed with which Drake was tarred and feathered as inauthentically Black says less about him and more about the reactionary nativism of cults of pure identity that police the boundaries of Blackness like a rogue and racist cop. In a single spurious stroke of Kendrick’s claustrophobic Blackness, Drake went from a brilliant embodiment of rap’s genius to a cultural carpetbagger who must prove that he deserves to be called Black when a white supremacist culture sees him as little else.

As debates about DEI rage, and as arguments abound about banning books and reshaping curricula by conservative forces, the kind of hip hop battle waged by Drake and Kendrick Lamar offers valuable lessons.

It must be said that light skin privilege is real. If Black folk combatted colorism with sayings like “the darker the berry, the sweeter the juice,” and “good Black don’t crack,” we might surely coin the phrase, “the lighter the skin, the lighter the sin,” since lighter complexions were often seen as less offensive than darker shades. I learned this up close as a light-skinned Negro child born in the late 50s with a father who was blue Black and whose radiant darkness evoked the revulsion of both hateful Whites and self-hating Blacks.

Drake’s light skin undoubtedly offers him at times the benefit of being “Black plus” — his epidermis symbolically and literally bleached in the genetic pools of Whiteness. But his skin is hardly light enough, nor his hair straight enough, to shield him from a one-drop rule that historically means anyone with an ounce of Black blood measures his or her identity in grams of color. Or, in his case, Grahams of color, as witnessed in the beautiful, bronzed skin of his father Dennis.

To say that Drake is White, to honestly believe that he is not Black, is to reverse centuries of belief and practice where we claimed biracial folk as our own. Frederick Douglass, Maya Rudolph, James McBride, Faith Evans, Bob Marley, Sade, August Wilson, Zadie Smith, and, most famously, Barack Obama, are light skinned mixed-race folk who are all deemed Black.

And dark-skinned figures like Clarence Thomas and brown-skinned figures like Candace Owens are undeniably Black but often viewed as figures who have betrayed mainstream or healthy and uplifting Black thought. Nothing about Drake’s beliefs or behavior suggest such a betrayal.

II.

To be sure, the chocolate charming Kendrick Lamar is seen as the quintessential Black rapper. His monumental album, To Pimp a Butterfly, a sonic compendium of useful Black rage turned outward, produced the anthem for Black Lives Matter, “Alright,” where Lamar declares, “We been hurt, been down before,” and that “we hate po-po” because they want to “kill us dead in the street for sure.”

But that is not the album for which Lamar snagged a Pulitzer. It was Damn, his follow up disc to Butterfly that announced a radical shift in Lamar’s awareness of, and investment in, religious cosmology and a profound rejection of heroic Blackness. It also echoed a racial theodicy that is more Max Weber than Martin Luther King, Jr. Damn probed the gulf between what Black folk get and what they deserve.

Except in this instance what they deserve is filtered through a theology of divine punishment for Black sin that is hardly distinguishable from the white supremacist denunciation of Blackness. There is an eerie convergence between the two, not intentional, to be certain, and yet no less troubling. It is the mirror image of Butterfly except the rage is turned inward.

Kendrick gained galactic Black credence on Butterfly, and it is that version of Kendrick that is juxtaposed to contemporary Drake in many commentaries. Drake was pummeled on social media, and his biracial background — his mother is White Jewish Canadian, his father Black American — was cynically conflated into suspicious Blackness and questionable racial authenticity.

To say that Drake is White, to honestly believe that he is not Black, is to reverse centuries of belief and practice where we claimed biracial folk as our own.

A widely circulated video of Drake discussing his Jewish heritage, including speaking of his bar mitzvah, suddenly marked him as an outsider. And, as Jews are often perceived, as a stranger. He was no longer Black and Jewish; he was simply White and Jewish. The showdown was between Black Kenny and White Drake. White Jewish Drake. Then Jewish Drake. This subtraction, grammatically speaking, of the nominal substance of Drake’s identity by the addition of adjectives that whittle away his Blackness, is both a sly racial semantics and a curious group alchemy.

Claiming that Drake is not just White but Jewish, too, conjures, not the necessity, but the specter of anti-Semitism. It is not that the recognition of Drake as Jewish clinches the case. But the insistence that he is automatically suspect because he is a White Jew surely does. Here Jewish is shorthand for the worst possible and most uncomfortable kind of Whiteness that carries a double whammy of being both racially and ethnically offensive.

The irony of such a claim, especially when pitched against the ineradicable Blackness of Kendrick Lamar, is that on Damn Lamar identifies with the Hebrew Israelites, a (Black) nationality that spurns Blackness. “I’m an Israelite/Don’t call me black no mo’,” Kendrick insists on “YAH.” As in Yahweh. Here is the rub: Black Israelites claim to be the direct descendants of the 10 lost tribes of ancient Israel.

So-called “White boy” Jewish Drake is being denied a Blackness he has always acknowledged — “light skin but still a dark [brother],” he raps on “Nonstop” — while so-called “Blacker” Kendrick insists he is not Black but is the true Israelite. To double down on the damnation, Hebrew Israelites are at once the chosen people of God who are also the recipients of a divine curse for disobedience and alienation from the Almighty. Lamar’s politics are in this instance driven by the complicated imperative to honor God by offering prophetic witness to the wages of Black wickedness.

III.

Such reductive and narrow thinking about race obscures the complicated character of Drake’s Blackness. “I always felt like an outsider,” Drake told journalist Katie Couric in 2010, recalling how he was teased as a biracial youth growing up in Canada who was both Jewish and Black. In 2011, he told the Village Voice that “I mean, I’m so light that people are like, ‘you’re White.’ That’s what I get more than anything, people saying, ‘you’re White, you’re not Black.”

If Drake is now being dragged by some Black folk amidst his public beef with Kendrick, Jewish youth were “close-minded and mean” to him as well. “Jewish kids didn’t understand how I could be Black and Jewish,” he told Vibe in 2013. He was the target of racist remarks from Jewish students too, some of whom hurled at him the word “shvartze,” a Yiddish racial epithet for Black people. The future artist was also reminded that he was Black when he visited his father in Tennessee, and they were denied service in shady establishments with few patrons but told that those places were full.

Drake insisted on his Blackness despite bruising encounters in his youth. While he has never spurned his Jewish identity, he understood early on that his identity is deeply rooted in Black culture. “At the end of the day, I consider myself a Black man because I’m more immersed in Black culture than any other,” he has said. “Being Jewish is kind of a cool twist. It makes me unique.”

Although his parents split when he was five years old, Drake was nevertheless deeply rooted in Black life through his father’s family. His father Dennis was a drummer with his own band, who also played at one time for Jerry Lee Lewis; his uncle Larry Graham played bass for Sly and the Family Stone and for Prince, while fronting his own group, and then enjoying a successful solo career in between; another uncle, Mabon Lewis “Teenie” Hodges, was a talented musician who penned songs like “Love and Happiness” with Al Green. And for good measure, his paternal grandmother babysat Tina Turner.

bell hooks asked where “is the context where Jews can come together with Black non-Jews and talk about the sense of betrayal of a historical legacy of solidarity?”

It is true that Drake’s Blackness is not routinely political. Unlike Kendrick, whose explicit Blackness, despite his claiming to have transcended it, upholds the prophetic criticism of internal and external political barriers to Black community, Drake’s Blackness is implicit and far more cosmopolitan and blissfully diasporic. That doesn’t mean that Drake is unaware of the racial contradictions that trace his light frame. Drake recalls on his song “You and the 6” how “I used to get teased for being Black, and now I’m here and I’m not Black enough/Cause I’m not acting tough or making stories up bout where I’m actually from.”

Drake embraced a more explicit political Blackness on “6PM In New York,” where he addresses the strained and often deadly relationship of Black citizens to the cops as Black folk mourn the dead and then quickly move on to the next hot social subject. “And I heard someone say something that stuck me with a lot/Bout how we need protecting from those protectin’ the block,” Drake says. He argues that “everybody can tweet about it/And then they start to RIP about it/And four weeks later nobody even speaks about it.”

The Black folk joining Rick Ross and Kendrick Lamar in challenging Drake’s Blackness, and chastising him for appropriating Black culture, have a brutish view of Black identity, and a painfully limited understanding of the politics of race. Long before he had an impressive body of work, Drake’s biracial Black body was curved by the despotic will of ordinary White bigots who failed to recognize his humanity, yet who couldn’t ignore his unavoidable Blackness. That is a feat achieved in reverse by Black critics who are equally pernicious in their blindness to Drake’s Blackness as they proclaim either that he is a “White boy,” or an insufficiently authentic Black man.

Then, too, from the beginning of his sojourn in song and rhyme, Drake was “dissed” because he lacked both hood pedigree and a requisite Black masculine stoicism. He was also knocked because he possessed an edifying emotional intelligence that permitted him to freely showcase vulnerability and sensitivity. It has long since become obsolete to equate Blackness with opaque ghettocentric patriarchy. “Sometimes some of my Blackest friends can be just as cruel by making you feel excluded or making you feel like, ‘You can’t get in on this,” Drake said in an interview with Rap Radar in 2019. “I associate myself as a Black man,” he continued. “It’s something I just acknowledge, and I keep it moving.”

Drake can acknowledge Blackness and move forward because he travels the glorious geographies and multiple maps of the Black Atlantic, which uplifts a vision of the rich and robust hybridity of Black cultures around the Atlantic. His very artistic existence chastises an exclusively American centered version of Blackness; his Black, Canadian, Jewish, biracial identity rebukes a chauvinistic and nationalistic vision of Blackness.

Drake is in many ways the Black Atlantic personified, a projection in body, and in sound and range, of the sublime variety of Black musical forms with which he experiments — hip hop, Afrobeats, reggae, dancehall, UK drill, British grime, tech house, Jersey club, amapiano, dance, electro, UK funk, trap, New Orleans bounce, soca, and so much more. The insistence on the Black monolith as the measure of complicated and comprehensive Blackness is a logical contradiction and suggests the undoing of a Blackness that lives more by nuance than negation.

IV.

The brutal fight over Black and Jewish identities may be as heightened as it is in the Drake and Kendrick hostilities because a similar vigor cannot be safely pursued in the tensions between Blacks and Jews around the war in Gaza. It is dangerous to interpret with equal energy the goings on inside two debased and demoralized communities as they seek to clarify their beliefs and take a stand.

The practice of free speech, the hallmark of a true democracy, may be truer of hip hop than in the country at large. It may be messy and morally murky, perhaps even frustrating and flattening, and at times dispiriting, but one may say more of what one believes far more readily in public dialogues created by hip hop than in the nation’s classrooms and town halls, and even in our naked or shrouded public squares.

One may love or hate Drake or Kendrick, say why that is so, offer reasons and justifications, and, beyond the name-calling or stereotyping that inevitably attends what often passes for public conversation these days, stake a claim without risking one’s life or career. The same cannot be said for many issues in the political spotlight, and the war in Gaza is one of them.

“At the end of the day, I consider myself a Black man because I’m more immersed in Black culture than any other,” Drake has said. “Being Jewish is kind of a cool twist. It makes me unique.”

The protests now sweeping college campuses in the aftermath of the evil visited upon Israel on October 7th of last year, and the evils of the brutal military actions taken by Israel against Palestinians in retaliation, have put kin and former allies at odds. Israel has every right to defend itself from fast terror; Palestine has every right to rebel against slow terror. Fast terror happens in obvious fashion as bombs drop, weapons are wielded, lives are lost. Slow terror occurs as institutions, societies, and their folkways and mores, punish populations with silent, or muffled, often invisible suffering and death. Fast terror is deadly and discontinuous; slow terror is deadly and daily.

Accounts of the rich legacy of Black and Jewish cooperation, and common struggle for justice, especially during the Civil Rights movements of the fifties and sixties, often ignore a nagging paradox: Black folk who draw inspiration from Old Testament accounts of Exodus and emancipation, and the resistance to oppression, apply such views to present day conflicts between Israel and Palestine. A nonviolent movement built on Biblical principles to garner Black freedom eschews the use of terror to achieve political goals. That same movement, inspired by the call for justice in the Hebrew scriptures, sides with the oppressed no matter their creed, color or religion.

When folk protest to achieve justice, the ends after which they aim must of course be contained in the means of their expression. If those who protest Israel’s present course cannot steer clear of anti-Semitism, and in turn, if pro-Israeli figures cannot steer clear of anti-Muslim practice or anti-Palestinian prejudice, they miss a useful lesson from the nonviolent branch of the Civil Rights Movement: to purge oneself of impure motives, violent methods and destructive ends.

bell hooks argued that Blacks and Jews must find a context where “either group can be critical of the other without being labeled racist or anti-Semitic.” hooks asked where “is the context where Jews can come together with Black non-Jews and talk about the sense of betrayal of a historical legacy of solidarity?” hooks continued:

What is the context in which Black people can be critical of Zionist policies that condone the colonization and exploitation of Palestinians? Where is the context in which Jews can question black folks about our attitudes and opinions about Israel, about Jewish nationalism? Unless these contexts exist we will not be able to create the kind of critical thinking and writing that can challenge and transform black anti-Semitism or White Jewish racism.

Ironically, as debates about DEI rage, and as arguments abound about banning books and reshaping curricula by conservative forces, the kind of hip hop battle waged by Drake and Kendrick Lamar offers valuable lessons. What better way to teach youth about what they deem useless literary terms, or the effective use of poetic devices, set over various musical signatures?

At the very least, the battle between Drake and Kendrick, beyond the personal vitriol, offers a display of the rhetorical mastery that each artist exhibits. Kendrick’s densely layered narratives and quadruple entendres merit listening time and again to decipher their meaning. Drake’s clever metaphors, crisp articulation, and verbal punch lines — and his use of enjambment and elongation — compose his creative wordplay.

Back in the nineties and the aughts, I testified before several congressional panels to oppose the banning of hip hop albums teeming with the guerilla literacies and homegrown verbal genius that many Black forces and figures sought to discipline and curtail. The disturbing and destructive presence of misogyny undoubtedly merited resistance, but the value of free speech is no more precious than when we disagree with its moral intent or its vicious consequence.

Back then it seemed that DEI stood for deny, eradicate and impede forms of Black knowledge and expression. No matter how troubling it may be, or how displeasing we find some of its elements, hip hop is a powerful forum to debate race, democracy, protest, resistance to oppression and the fruits of diversity.

Of course, we should conduct such debates with a level of civility that marks our profound respect for the humanity of even our most bitter opponents, something sadly missing in the Drake and Kendrick debates. But when we listen to the tenor of contemporary political debates, where vicious name calling, and autocratic flourishes, are matched by the support of anti-democratic desecrations of some of the most sacred civic space in our democracy, Drake and Kendrick are tame by comparison.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the superstar Drake’s grandmother babysat. It was Tina Turner.

Michael Eric Dyson is a renowned professor, now at Vanderbilt University; an author of 25 books, including seven New York Times bestsellers; and a public intellectual who has won several awards, including the Langston Hughes Medal, American Book Award and 2 NAACP Image Awards.