When state Sen. Amanda Cappelletti was growing up in Boyertown, PA, she had an elementary school librarian whose name she can only vaguely recall — “something like Mrs. LaBan, I think,” she says — but whose “fun voices she’d make during storytime” Cappelletti has never forgotten.

“She had such an impact on me, opening me up to the world of literature,” Cappelletti recalls. “And my parents loved that I was reading books, learning to think critically and ask questions about my world.”

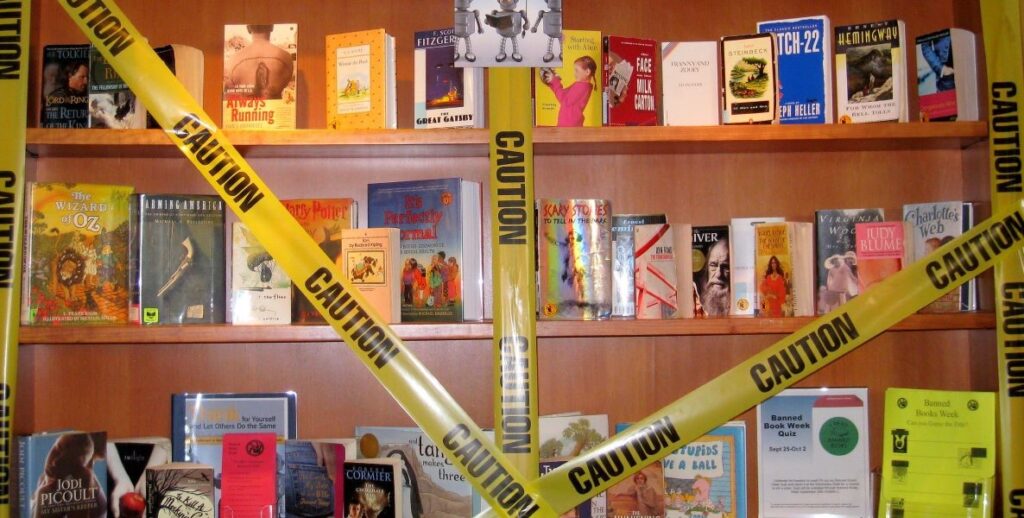

Cappelletti recalls “Mrs. LaBan” introducing her to difficult but powerful books that the librarian knew she could handle — including Lois Lowry’s young adult dystopian novel The Giver and the real-world dystopian Diary of Anne Frank. Today, if a very few but very loud activists have their way, librarians like LaBan might not be able to share those stories — among the regularly banned books in America — with girls like the young Amanda Cappelletti.

That’s why the Senator on Monday introduced legislation that would, effectively, ban book bans in the state of Pennsylvania. Inspired by an Illinois law passed earlier this year — and by calls from her constituents to do the same here — Cappelletti’s bill would require all publicly-funded libraries, including those in schools, to issue statements promising not to remove books “because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

“Reading a book that demonstrates the life of someone who is not like us should be something we do more of so we can understand more.” — Sen. Amanda Cappelletti

What Cappelletti’s bill would not do is prevent parents from having a say in what their children read. “There are already policies in place that let parents exempt their children from reading certain works of literature,” Cappelletti says. “I don’t deny them that right. But I have a child, too — when books are not in the library, you’ve taken away my right to have my child check out that book.”

Chester County Rep. Paul Friel has introduced a related bill in the House that seeks to ease the burden of fighting book bans away from librarians and educators. Cappelletti says there is a policy hearing on the issue scheduled for this week.

This should be a no-brainer, a bipartisan high-five, a unanimous declaration that, duh, of course we are not going to ban books from libraries in the year 2023. Instead, it’s likely Cappelletti’s bill will die in committee in the Republican-controlled Senate. Lancaster County Republican Sen Ryan Aument told Lancaster Online this week that while he personally opposes book bans, he is skeptical Cappelletti’s bill will pass. Aument himself has proposed a bill that would require schools to alert parents of any books with sexual content so they can “opt in” for their children.

Why, at a time when you can get Republicans and Democrats to agree even on criminal justice reform, can we not all agree that books — words, ideas, images, imagination — are worth protecting?

It’s like we have the vapors

The answer, of course, is cultural politics. A PEN America report found 3,362 instances of individual books being banned in the 2022-23 school year, a 33 percent increase over the year before. Florida (shocker) banned the most books. Pennsylvania last school year was number five among the 33 states that pulled books from library shelves last school year — including in Central Bucks, whose school board passed a policy prohibiting “sexualized content” and had received 60 book challenges by the start of this school year.

Parents on both sides of the aisle have called for the removal of books from curricula, but by far most challenges have come from conservative-leaning parents or activists, like Moms For Liberty. According to a Washington Post investigation, nearly half of all calls for removing books filed in the 2021-22 school year contained LGBTQ+ characters or themes; 36 percent dealt with race or racism; and 61 percent referenced some kind of “sexual” content. (To learn about some of these books, check out MSNBC’s Ali Velshi’s Banned Book Club.)

You know what else the Post investigation found?

The majority of the 1,000-plus book challenges analyzed by The Post were filed by just 11 people. Each of these people brought 10 or more challenges against books in their school district; one man filed 92 challenges. Together, these serial filers constituted 6 percent of all book challengers — but were responsible for 60 percent of all filings.

This is not democracy, or even populism, or even popular. Most Americans oppose book bans, including most Republicans. Most trust their teachers and school librarians who, Cappelletti points out, are experts with degrees in teaching children — and who, it should be said, are far better guides for helping them with difficult material than the other place children go to read about all the things parents are afraid of: the internet.

Truthfully, most Pennsylvanians probably don’t care about the argument over books at all. It’s an issue made up to distract us from the more important things our leaders should be doing. “Being afraid of the word gay, or of a book that has a same sex relationship in it is not the greatest problem for most people,” Cappelletti notes. “They worry about how much money is in their paychecks, how much water is leaking from the roof, education not getting funded equitably. These cultural wars don’t matter as much.”

Democracy, though, does matter

As Elaine Maimon wrote in The Citizen this year, the Illinois bill Cappelletti used as a model was the first in the country to issue consequences for public libraries and schools that remove reading materials because of “partisan or personal disapproval.” (New Jersey legislators are considering a similar bill.) Libraries in Illinois will lose state funding if they fail to follow the American Library Association Bill of Rights, seven rules that are a beautiful distillation of everything a society of ideas and free expression should be — including freedom from censorship and inclusiveness of all points of view.

This is not democracy, or even populism, or even popular. Most Americans oppose book bans, including most Republicans.

The Library Bill of Rights was first adopted in 1939, probably not coincidentally at the same time as books were being burned in Nazi Germany. It was our country’s declaration that we are not that — we are for books and the difficult ideas they include — when the free world was afraid that it might not survive World War II. Now we are more afraid of being canceled or triggered or thrown out of office or somehow warping our children by letting them explore what it is to be fully-formed humans who have feelings and desires and unorthodox inspirations and are even — gasp — sometimes really badly behaved.

It shouldn’t need to be said — but maybe it does? — that reading a book about gay people will not turn children gay. But reading about gay people and Brown people and White people and all the weird and beautiful experiences of humans can change people by opening their eyes and their souls to the strangers in their midst. Why would we want to limit that? Why would we want to build barriers, when everything we know about how societies thrive requires us to lean in more and see each other’s humanity?

Cappelletti says she often gets questioning looks when she talks about encountering one of her favorite books, The Kite Runner, about a Muslim family in Afghanistan, while a student at Chestnut Hill College, a Catholic institution — as if somehow that was an impassable breach. “That we were reading and delving into that literature was so important,” she says. “Reading a book that demonstrates the life of someone who is not like us should be something we do more of so we can understand more.”

Then-Senator John F. Kennedy once said in a speech something that seems more true now, when our democracy seems perpetually teetering on the edge, than it did 60 years ago: “If this nation is to be wise as well as strong, if we are to live up to our national promise and live up to our national destiny, then we need more new ideas for more wise men reading more good books in more public libraries.”

How about it? No place better to start than where our democracy took off — here in Pennsylvania.

MORE FROM THE CITIZEN ON BANNED BOOKS