Has there ever been a movie more befitting its time than A Beautiful Day In The Neighborhood, wherein Tom Hanks brings children’s TV star Mister Rogers back to life? There he is, again, on a screen before us, donning that red cardigan, his slowness of speech and gentleness of spirit a de facto prescription: It’s time to make America empathetic again.

![]()

Over the course of two hours, we see Fred Rogers movingly model a type of humanity for Vogel, who seems mired in anger, disconnected from his own feelings. It is Vogel—and, by extension, us—who grows as a result.

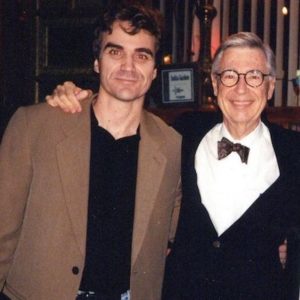

The film is adapted from a real life 1998 Esquire feature penned by Tom Junod, long one of the nation’s premier magazine writers. While some significant details differ between article and movie—Junod never punched out his own father at his sister’s wedding—Vogel, as played by Rhys, is Junod. He wears his ’90s-era black turtleneck, he turns his head just so when asking a particularly penetrating question of a subject. I know this because Junod has been a friend for the last couple of decades at least, someone who I’ve alternately learned from, laughed with, and … hated for his prodigious talent.

We hadn’t spoken in a few years, owing to the natural entropy of middle-age relationships, but watching the film, I knew I had to reach out. Because, while I was absorbed in the movie’s storyline, I was also wrestling with what it says about Junod. For me, Junod had never been the embodiment of cynical, gotcha journalism; instead, his work has been, on balance, about elevating magazine writing to art form. In the ’90s, he’d won so many National Magazine Awards, and been nominated for so many others, that I once introduced him to my dad as “the Michael Jordan of magazine writing.”

Junod at his best, I thought, did what Mister Rogers would have us do: elevate values like empathy and curiosity, and just generally muck around in human complexity. In stories like The Rapist Says He’s Sorry, he could make you feel for a rapist; in The Abortionist, he brings you into the violent underworld of the abortion wars, profiling a Florida doctor and presaging his ultimate slaying at the hands of true believers; and in The Falling Man, Junod takes us on a deeply reported, intimate travelogue into the harrowing 9/11 photograph of a body hurtling to the ground from the North Tower. More recently, his report behind the scenes of the death of Muhammad Ali for ESPN still haunts. That’s our jaded journalist?

“Funny, I was in Pittsburgh last week and they set up a satellite link to do TV shows like Good Morning, Terre Haute across the country to promote the movie,” Junod said when I caught up with him at his Atlanta home last week. “And they all ask the same questions. I had about 15 questions about being a jaded journalist.”

One time, on a panel of writers that included Richard Ben Cramer, Rick Bragg and Susan Orlean, he challenged them to “go there” and not hold their fire. Afterwards, an audience member came up to him: “Are you okay?” she asked. “How can you do this and not have it all catch up with you?”

Most of all, Junod was relentless about getting the story—and he was learning the cost of that on one’s humanity. “I remember doing a story for Esquire about a twin who had killed his twin, and it was deemed accidental, which I called into question,” Junod said. “The mother called me. I still remember that call. I was in the Paramount Hotel in New York City, in a darkened room. She was, like, ‘I can’t believe you would do this for a magazine story, that you would go in and destroy a person who has already been destroyed for a magazine story.’”

Junod at his best did what Mister Rogers would have us do: elevate values like empathy and curiosity, and just generally muck around in human complexity.

At the time, Junod felt like anything was in-bounds. But, as with any pugilist, even literary ones, scar tissue accumulates. He wrote a devastating portrait of legendary Nebraska football coach Tom Osborne, whose players assaulted women in disproportionate numbers. The pious Coach Tom—a future congressman—comes off as a Father Flanagan figure who just might not like women all that much, a conclusion I shared when I later wrote about the coach’s political campaign. After Junod’s article appeared, a note came in the mail: “All the words in the world are not worth your integrity,” the coach had written to him.

“She likes to answer to her nickname: Placenta,” I quipped, not missing a beat, exhibiting my weakness—glibness in place of realness. He laughed, calling me an asshole. We were two clever people, basking in our cleverness. Why do I cringe now at the memory? Because as the years have ensued, as I’ve disappointed people, as I’ve disappointed myself, I’ve come to see that I was never quite as clever as I thought. That shift is something A Beautiful Day In The Neighborhood hints at and gets mostly right: The eloquent example of Fred Rogers suggests that taking stock of, and expressing, your feelings feels better, and is far more enlightening and healthier, than masking them in detached irony or double entendres about which way Kevin Spacey bats.

That’s also a message I’ve always taken from Junod’s work, and from the man himself. There’s a great scene in the film right out of Junod’s article, in which a group of kids on a subway car serenade Mister Rogers in a spontaneous rendition of his theme song. Rogers, played by Hanks, looks on in open-mouthed, wide-eyed wonder. Something in his child-like expression felt familiar to me.

The eloquent example of Fred Rogers suggests that taking stock of, and expressing, your feelings feels better, and is far more enlightening and healthier, than masking them in detached irony or double entendres about which way Kevin Spacey bats.

Twenty years ago, while I was writing a book about Allen Iverson, Junod was in town, profiling our then-police commissioner, the late John Timoney. I remember how psyched he was to describe Timoney’s face: “…that splatted knob of a nose, that shadowed dent of a mouth, that bulletproofed brow, those broken-glassed blue eyes, those flyaway ears, that whole topography of furrow and ditch and crevasse, all topped by the reddish-brown hair of a little boy, without a strand of gray.”

While he was in town, I took Junod to a Sixers game, where we sat, as I used to, among the beat writers and broadcasters along press row. In that group, an insider ethos applied; we’d gossip during the games and judge the coach or the players. That game, during a timeout, the team’s mascot—Big Shot, RIP!—was dancing in the stands, and the house band was rocking some Sound of Philly classic, and I glimpsed up from my stat sheet to see Junod, staring up and out at the spectacle before him, his mouth agape and eyes wide just like Hanks in the movie, taking it all in. He was fully in the moment, basking, while I, and my compatriots in the press, had been oblivious.

In an essay in The Atlantic timed to the movie’s release, Junod plays with what his friend would say about where we’re at now, as an extended, fractured neighborhood:

Although he made his living speaking to children, his message and example endure because he found a way to speak to all of us—to speak to children as respectfully as he spoke to adults and to speak to adults as simply as he spoke to children…his message to doctors was his message to politicians, CEOs, celebrities, educators, writers, students, everyone. It was also the basis of his strange superpowers.

He wanted us to remember what it was like to be a child so that he could talk to us; he wanted to talk to us so that we could remember what it was like to be a child. And he could talk to anyone, believing that if you remembered what it was like to be a child, you would remember that you were a child of God.

The question, then, isn’t what Fred would do, what Fred would say, in the face of outrage and horror, because Fred was the most stubbornly consistent of men. He would say that Donald Trump was a child once too. He would say that the latest Twitter victim or villain was a child once too. He would even say that the mass murderers of El Paso and Dayton were children once too—that, in fact, they were very nearly still children, at 21 and 24 years old, respectively—and he would be heartbroken that children have become both the source and the target of so much animus.

He would pray for the shooters as well as for their victims, and he would continue to urge us, in what has become one of his most oft quoted lines, to “look for the helpers.”

Junod is now at work on a book about his father, Lou Junod, who he’s touched on in magazine articles through the years, as in a recent ESPN piece about his late father’s gambling:

My father sold handbags and made a lot of money doing so. But the bookies sold opportunity, and they were relentless. They called all week long, and on Saturdays and Sundays they called all day long, proffering exotic parlays and teasers. My father spoke to them in code…My mother, Fran, listened as intently as I did…She fretted, wringing her hands the way she did when she sat as a passenger in the car and my father, often in anger, started speeding. “Oh, I hate those parlays,” she’d say. “I hate those teasers.” But ultimately she had no choice but to include herself in my father’s life as a player, having been excluded from his other life as … well, a player. My father was a man of many vices and an untold number of secrets. But his gambling was the one secret in which we could all participate.

It was the family vice.

I suspect it will be a big book, one that deals honestly with the multilayered nuances of the so-called Greatest Generation, a euphemism Junod calls “an unfortunate whitewashing.” Also in the works is a collection of his magazine pieces over the years, which, taken together, ought to advance a sui generis, and often contrarian, take on America. The prospect of both excite me, for, though we’re awash in information, we also suffer from a dearth of wisdom. Which brings us right back to Fred Rogers.

Toward the end of our call, I told Tom I was sorry we hadn’t been in touch in a few years. “Well, we’re talking now,” he said, matter-of-factly. Sounded exactly like something Fred would say.