As billows of black, toxic smoke rose into crisp autumn air in Philadelphia last week, many of us, especially throughout Southwest Philly, could actually smell that something was not quite right in the air (you could literally taste the tires), and many of us—especially those with chronic respiratory ailments—were choking and coughing to the reality of another mass pollutant catastrophe unfolding in Philadelphia.

Yet the City of Philadelphia (whom we presume could smell that same putrid scent) didn’t bother to tell the majority of its residents that they were breathing in the dangerously toxic fumes of burning tires or how to protect themselves and their families.

So, we’re left to ask exactly why? What happened and who’s responsible? What will the response be? How can we prevent this from happening again? We feel totally powerless, as concerned and impacted residents, in the effort to demand answers and action since piles of trash and unsafe junkyards have become a familiar staple of Philadelphia life.

Unkempt and contaminated auto body shops in Southwest Philly are so bad, for example, that even the Public Interest Law Center is conducting a resident survey to determine next step legal and policy recourse. And that feeling of powerlessness? That worsens once we get deeper into Blacker, Browner and lower-income zip codes where these types of environmental calamities happen quite frequently, but on a smaller scale, while the City infamously shrugs on about it.

The City should have known this was going to happen and it knows it will keep happening. We shouldn’t forget the last apocalyptic-looking junkyard fire in 2018 in the city’s Kensington section, a disaster of literal dumpster fire dimensions that residents—again, mostly Black—had warned city leaders, Licensing & Inspection authorities and others about for many years, as ecoWURD detailed in its investigative reporting at the time. That fire happened, but nothing changed.

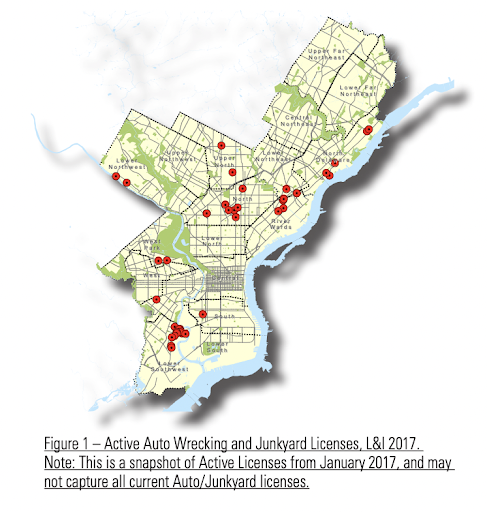

Indeed, as predicted, another junkyard fire a month later delayed SEPTA and Amtrak service. More than 40 “actively-licensed” auto wrecking and “junk yards” remain in plain sight and are “disproportionately sited in Lower Southwest, North, Riverwards, and North Delaware Districts,” according to the city’s own Planning Commission report. The 160 acres of land devoted to these noxious land uses is an accumulating ticking public health time bomb that serves no purpose other than to slowly choke us through long-term exposure to pollutants and the risk of catastrophic fires. The urgent proactive planning and enforcement necessary to keep communities safe continues to be absent.

On November 10th, 2021, the morning after the latest “Tire Fire” in Philadelphia, after everyone spent a night in their homes breathing in toxic fumes, City officials gaslit residents instead by insisting that it’s “not hazardous.” But exactly how is that? Since when is breathing in large quantities of tiny burnt particles of tires healthy?

One of us, Christina Rosan, was signed up for ReadyPhiladelphia text alerts from the City’s Office of Emergency Management which notifies residents about Covid-19 vaccine updates, thunderstorms, flooding, and Philadelphia Health Department alerts. Yet she received no alert, despite what was clearly a dangerous air pollution emergency.

Instead, she constantly checked the PurpleAir quality monitor on her house (which she has because she studies the urban environment) and watched in terror as the dangerous particulate matter numbers kept soaring: at one point, a 10-minute average EPA PM 2.5 air quality index of 445. That’s just unspeakably bad; 300 is when it’s officially at a health warning of emergency conditions. Not knowing what else to do, but smelling the burning tires, she slept in her kids’ room while everyone wore K95 masks to sleep as she blasted a HEPA air purifier; she hopes those precautions reduced her family’s exposure, but she will never know what the exact impacts are.

If PurpleAir monitors right in the middle of the fire zone in West Philadelphia are off-the-charts— giving us real time numbers of what’s really happening with city air—exactly what standard or method of city-wide air monitoring is the City using to determine it’s not hazardous?

This event makes it clear that Philadelphia’s Air Monitoring Network of only 10 air monitors fails to capture more granular air pollution data. This small, inadequate network isn’t even located in all neighborhoods and, somehow, it’s absent from huge swaths of West Philadelphia despite the high concentration of hazardous land uses. This makes us unprepared as a City to deal with air pollution and other emergencies (which may be very localized) while preventing us from promoting and enforcing environmental justice in neighborhoods across the city since we really don’t know what’s being emitted from these noxious land uses on a daily basis.

We need to develop a new, robust, state-of-the art, city-wide air monitoring system immediately. We must then connect it to preparedness, planning, monitoring, regulation, enforcement, and emergency response. City leaders and public health officials must coordinate and invest in a system that adequately captures what’s truly happening on the ground at a neighborhood level. Then they need to use the data to enforce violations which means they need to also invest in adequate city personnel and encourage more coordination across city agencies to address environmental justice and emergency preparedness.

A better air pollution monitoring system (which could be strengthened through collaborations with major academic and medical centers across the city), makes us more ready for emergencies and addresses the cumulative impacts of the concentration of multiple noxious and industrial uses in environmental justice (EJ) communities. If designed effectively, the monitoring system could also be designed to anticipate and prepare us for climate crisis events.

As a part of a new city-wide system, the City could engage Philadelphia residents as citizen-scientists through the installation of low-cost monitors (PurpleAir or other brands) in their neighborhoods that they can check in the event of an emergency, use to better understand their environmental burdens, and advocate for regulation and enforcement of noxious land use.This could translate into green space and environmental protection investments (Rosan is working with the Clean Air Council and other community, university, and City partners on a planning and preparedness pilot project).

Neighborhood-level data could capture environmental injustice happening across the city and strengthen calls for stricter regulation and enforcement of noxious facilities, the closure and remediation of existing toxic spaces, and the denial of permits for new polluting uses in EJ neighborhoods. This would be a major win for the health of thousands of Philadelphians. By reducing the persistent and cumulative exposure in EJ communities, we could give back years of life to Philadelphians, particularly Black and Brown residents. That’s how the city should promote racial justice and commit to Black Lives Matter.

In the wake of the latest tire fire, there are serious questions of not only data, monitoring, and enforcement that we should be asking, but questions around trust and credibility: Can we trust Philadelphia’s Department of Public Health and other City agencies to create a strong enough response that keeps us safe? Right now, by failing to take necessary precautions and protect public health in the event of an emergency like the November 9-10th fire, the City is essentially conducting a major epidemiological experiment with a large number of its population.

The impacts of breathing this air overnight may not be immediately noticed or known. For many residents of EJ communities, the November 9-10th exposure will just be one of many events that reduce their overall life expectancy and lead to numerous negative health outcomes.

In the meantime, do we have a plan for emergency response and evacuation? We didn’t even get an emergency text message to tell people to put their masks on or breath through a towel or to leave town. There must be protocols for how to deal with these disasters, but they were absent.

This presents a very troubling picture of a city asleep at the wheel when tasked to prepare, protect, monitor, care, respond to or offer some semblance of a comprehensive response plan for how it tackles its generations-long trash, illegal dumping, toxicity and pollution crisis. What happened on the night of November 9-10th is not just another junkyard fire (a sentence that we can’t believe we need to write), but it’s emblematic of ongoing environmental injustice that is so deep and entrenched here that it’s become normal to simply ignore disasters-in-waiting.

Black and Brown populations, the city’s majority, have been warning us about these dangers for a long time while they’ve lived (shorter lives), slept, worked and endured the “Struggle Space”—and we’ve continued to ignore them until a tire pile fire’s toxic fumes invade the air of White affluence to give many a taste of that pollution run amok. Maybe now, City Council will take action. But without the monitoring or evidence to argue that something is drastically wrong (like the image above from the one PurpleAir monitor on the author’s house), air pollution events can easily be ignored, viewed as ephemeral, or inconsequential, even as our bodies are affected. We do not treat air pollution as the killer that it is.

Not only does the City tolerate hazardous waste sites, it actually gives them a license and allows them to keep operating even after a fire. Not only is the outside air quality endangered, but the inside air quality of schools is oozing with cancerous toxicity. Trash piles and untold thousands of vacant lots citywide harbor illegal dumping sites. Seemingly countless auto shops and scrap yards hoarding old tires that are either fire hazards or nests for disease-carrying pests litter Philadelphia’s most distressed neighborhoods.

This results in not just a bad air day or a smelly nuisance—this ends up slowly killing fellow residents: Philadelphia’s child asthma rates are double the national average and 75 percent of all pregnancy-related deaths in our city involve Black women. That’s not genetic or an accident—that’s environmental injustice unfolding right before our eyes.

As this fire and its fumes raged on, City Council members were either deflecting or pointing fingers on Twitter rather than asking themselves and their staff why they keep walking or driving past these disaster sites every day. These conditions are unacceptable and we hope that City Councilors use every tool in their arsenal to understand what went wrong and how to prevent this from happening again. We need a serious citywide gut check on this city’s persistent failure to monitor, regulate, and remove these poisonous places across the City, particularly in Black communities.

Why do we live in a city where “the latest Tire Fire” is normal and expected? Why can’t our existing monitoring and emergency response systems detect these air quality events and respond accordingly? Why do city officials keep ignoring environmental justice concerns, complaints, and warnings from Black and Brown residents? Let’s stop waiting for the next junkyard or tire fire to finally care about environmental justice. Let’s listen to EJ communities and work to protect them.

Charles Ellison, CPM is Senior Fellow for the Council of State Governments Eastern Regional Conference Council on Communities of Color, Executive Producer/Host of “Reality Check” on WURD and Managing Editor of ecoWURD.com. He can be reached on Twitter @ellisonreport.

Christina Rosan, MCP, PhD is associate professor of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and is the co-author of a forthcoming book Reimagining Sustainable Cities. She is working on an NSF funded research project, PREACT (Planning for Resilience and Equity through Accessible Community Technology), a multipurpose and multi-scalar climate preparedness and neighborhood planning software application informed by community needs and assets, to be piloted in the city of Philadelphia. She can be reached on Twitter @christinarosan.