Jeff Brown is a big, cheerful back slapper, as visits to any of his soon-to-be 12 Philly area grocery stores attest. In fact, at the entrance to his ShopRite at 67th and Haverford, there’s a life-size (albeit slimmer) smiling cardboard cutout of the social impact entrepreneur, welcoming customers, many of whom have been shopping there multiple times a week for years.

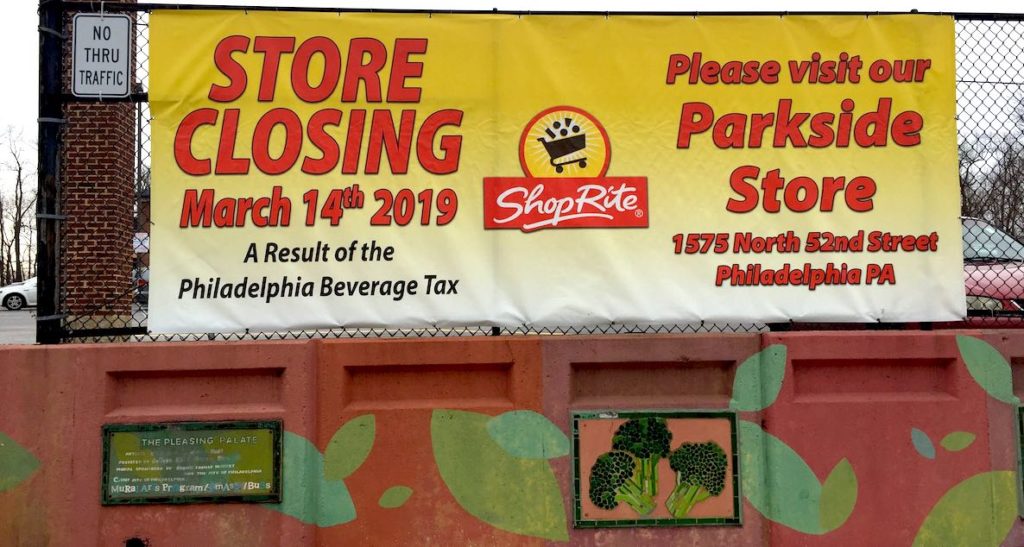

But that’s a streak that will end March 14, when Brown will close this particular ShopRite, a casualty of Mayor Kenney’s sweetened beverage, or soda, tax. The closure will qualify the neighborhood around 67th and Haverford Avenue officially as a “food desert,” which is defined by the United States Department of Agriculture as an urban neighborhood lacking in access to fruits, vegetables and other whole foods because its residents live more than one mile from a supermarket.

Brown did not sound like his usual garrulous self when I caught up with him Wednesday night, after a day at the store breaking the news to employees and customers. “It was an emotional day,” he said, his voice thick with emotion. “People were crying all day. We do what we do in food deserts to help people, and when it works, it’s like this little miracle that solves a whole lot of social problems. When it doesn’t, it’s tragic.”

Here’s a modest proposal, Mr. Mayor: Head on over to 67th and Haverford, and talk to the folks who hired you. You’ll hear what I heard: Of the customers I spoke to, none had cars and most were purchasing soda — proof of just how regressive the tax is. Those with cars had made the free market choice to shop in the nearby ‘burbs.

The saga of Philadelphia’s soda tax war is about more than arcane tax policy, and it’s about more than who may be up and who may be down in this year’s mayoral election. It really gets to a big philosophical question: Just what does it mean to be progressive nowadays?

Mayor Kenney and his allies speak the lingua franca of progressivism, but when what you hold up as your signature accomplishment is a tax, as opposed to the program it might fund, and when that leads to the expansion of a food desert in a city with the worst poverty in the nation and among the highest tax and lowest economic growth rates … You have to ask: Just how progressive are you?

Yesterday, I went to Brown’s store at 67th and Haverford to get a sense of the human cost behind Kenney’s tax. I saw an elderly, predominantly African American clientele, many of whom walk to the store three times a week — for food, yes, but also for connection and community. “I don’t know what I’m going to do,” said Betty, an African-American woman who, when I asked her last name, said, “just leave it at Betty.” She doesn’t own a car and she says this store wasn’t the neighborhood’s first casualty to the soda tax. “We had a convenience store up around the way that also closed because of the tax,” she said. “They want to tax something? Tax weed!”

Many customers I chatted up couldn’t understand how soda sales alone can hold the fate of an entire neighborhood. That’s because it ain’t really about the soda. Brown’s sweetened beverage sales are only down 3 to 4 percent. But his overall sales are down 23 percent, translating into a yearly $1 million loss, because when customers (especially those with cars) get their sweetened drinks mere blocks away across City Line Avenue, that’s where they do all their shopping.

I’ve known Jim Kenney for 20 years, and I’ve got to believe he doesn’t dye his hair orange when nobody’s looking. Instead, he’s just too inside the fight, too focused on winning to stop and consider who will be losing.

Talking to Betty and other customers at 67th and Haverford — some saddened, some irate — I couldn’t help but wish Mayor Kenney walked among them, up and down these aisles, to take in the picture of his progressivism. As I’ve written, I was initially agnostic about the soda tax and I remain convinced of the efficacy of pre-K — if it’s competently implemented, which is far from guaranteed when we’re talking about an administration that wasn’t even reconciling its own checkbooks until it was called out on its breach. But now that the Black Clergy has pulled its support for the regressive soda tax, and now that a grocery store in a food desert is closing because of it, it seems irrefutable that the tax perverts progressive values.

The Inquirer disagrees, having run an editorial recently that urged the city to “stop arguing about” the tax, after Councilman Allan Domb filed a resolution to hold hearings on it. The issue has already been over-litigated, the Inquirer argued. But has it? Voters like Betty never actually had their say.

Remember, during the 2015 mayor’s race, then-candidate Jim Kenney pledged to pay for pre-K and Rebuild without raising taxes; zero-based budgeting, a truly innovative approach that would have exposed all sorts of fat in the city budget, was going to foot the bill. No surprise, then, that it was quickly and unceremoniously abandoned.

Instead, Kenney’s strategy has been to tax, and tax again. He inherited a $3.9 billion budget and has ballooned it to $4.7 billion, a 17 percent hike, with hardly any return to show on our investment. When questioned by Brown and others about the efficacy of taxing the likes of Betty, Kenney’s response is ironic, given his outspokenness on national matters. He goes full Trump, attacking his critics personally when he can’t engage them on the merits in a policy debate.

This week, for example, Kenney responded to the ShopRite news by suggesting, as he has in the past, that Brown is lying. I’m not kidding; the Mayor would have us believe that Brown is closing a store when he doesn’t have to in order to make a political point. The administration points to an ongoing study by Harvard, Penn and Johns Hopkins that has never been released — and that was paid for by soda tax proponent Michael Bloomberg — that is reported to find that area grocery sales haven’t declined since the tax. Of course, it’s a little hard to argue with a study that hasn’t been released, but suffice to say: Any consideration of the health of the grocery industry, like any business, ought to take into account both income and expenses.

Relying on a mysterious study is one thing, but Kenney’s Trump-like personal attack on Brown is a sign of increased desperation. “We are always concerned when a retailer is ‘struggling,’” the Mayor’s spokesman said in a statement to the Inquirer, linking to an article about Brown’s purchase of a pricey Rittenhouse Square home.

“Food insecurity is growing here, and we have the worst poverty in the nation,” Brown says. “And this mayor’s solution to poverty is to tax poor people and cause them to lose their jobs. It’s insane. It’s an ideology that leads to poor outcomes for the people you say you’re trying to help.”

This, of course, is a shameful, Trump-like personal attack — waged against someone with impeccable progressive bona fides, as President Obama acknowledged in his 2010 State of the Union address, when Brown sat next to Michelle Obama and was honored for using his entrepreneurial skills to affect positive social change in distressed inner-city neighborhoods.

“Food insecurity is growing here, and we have the worst poverty in the nation,” Brown says. “And this mayor’s solution to poverty is to tax poor people and cause them to lose their jobs. It’s insane. It’s an ideology that leads to poor outcomes for the people you say you’re trying to help.”

A little history may be in order here. Brown first started servicing traditional food deserts at the behest of City Council. Along with the state and private partners, an innovative model was put together in a famously small margin business that allowed fresh food to get into parts of the city where there had — literally — been none. “Isn’t this what we want, entrepreneurs stepping up to help solve social problems?” Brown asks.

Brown’s model was always a very delicate fiscal operation. He has long been able to make the numbers work thanks to innovative public/private partnerships that helped him handle his costs, a fragile algorithm that has been imperiled by the soda tax. Brown took advantage of the Fresh Food Financing Initiative, a collaboration between the state and the Reinvestment Fund and nonprofit lenders; with minimal investment and risk, public outlays have helped defray the cost of higher quality food. Left to its own devices, after all, we’ve seen what the free market brings to the inner city: Artery-clogging fast food spots and junk food-laden Dollar Stores.

By any measure, Brown’s is a progressive success story, someone who has not only stayed and serviced neighborhoods others ran from but has also hired from those neighborhoods, including returning citizens. His stores not only bring affordable, fresh food to low-income neighborhoods, they also provide in-house nutrition counseling and social work services. They are de facto community centers.

Even now, when he’d be forgiven for flipping the city the bird, he’s pledged not to lay off the 111 workers at 67th and Haverford. He’ll transfer them and eat the cost, eventually making it up in attrition and turnover, provided other stores remain afloat. He’s even struck a deal with Lyft to provide rides — at his expense — for his shoppers to get to and from his Parkside store, some two miles away. Yesterday, customers were frowning at the prospect. “I don’t use Lyft,” one said dismissively, which is why Brown’s staff is spending the next two months giving Lyft tutorials to customers who don’t know right now where they are going to get food on a regular basis.

All that adds up to what ought to be the definition of a good corporate citizen, yet Brown finds himself vilified by a mayor who is, at best, in denial about the problem his tax has created. The closure at 67th and Haverford might only be the beginning. Its lease was up; when other food desert grocery leases expire, look for more closures, and more neighborhoods sliding backwards under Jim Kenney.

Brown says he is a past contributor to Kenney’s political coffers, but he’s never heard personally from the mayor about this issue. “I’ve invested $7 million in this store and can’t make the numbers work,” Brown says. “I’ve put my money where my mouth is. Seeing that, every politician I’ve ever known would pick up the phone and say, ‘Is there some way to help you mitigate these troubles?’ Not Jimmy.”

The saga of Philadelphia’s soda tax war is about more than arcane tax policy, and it’s about more than who may be up and who may be down in this year’s mayoral election. It really gets to a big philosophical question: Just what does it mean to be progressive nowadays?

Instead, what we get from Kenney is what we get from Trump, snarling personal attacks and government by press release. The problem for the mayor is that, if every critic harbors hidden, evil intent, if every question about his tax is really a bought and paid-for script read at the behest of “Big Soda,” then we really do have a local Trump, a leader who is allergic to honest debate and practical problem solving, and whose rhetoric debases the public conversation.

I’ve known Jim Kenney for 20 years, however, and I’ve got to believe he doesn’t dye his hair orange when nobody’s looking. Instead, he’s just too inside the fight, too focused on winning to stop and consider who will be losing.

So here’s a modest proposal, Mr. Mayor: Head on over to 67th and Haverford, walk the aisles, and talk to the folks who hired you. You’ll see what I saw and hear what I heard: Of the five or six customers I spoke to, none had cars and most were purchasing soda — proof of just how regressive the tax is, just like Bernie Sanders said. Those with cars had made the free market choice to shop in the nearby ‘burbs; those without wheels were stuck here, paying more for their sweetened beverages.

So head on over to 67th and Haverford, Mr. Mayor, so Betty and her crew can speak some common sense truth to power. Maybe hearing from them will help you widen the aperture of your lens.

“Pre-K is cool,” they’ll tell you. “But find a way to pay for it — as you promised — that won’t hurt poor people, Mr. Progressive.”