A recent article in The Philadelphia Inquirer explored the legacy of the 70-plus Rite Aid pharmacies that have closed in the Philadelphia region since 2022. While these store closures are problematic because many of them sit vacant for months afterward, a bigger issue remains with those stores that are open: their Plexiglass locked shelves. The problem isn’t just at Rite Aid, but at CVS, Target, Walmart and other places that sell laundry detergent, formula, diapers, deodorant, toothpaste and other basics.

A combination of factors has led to the abundance of locked shelves. CVS, Rite Aid and Target were among the many, many brick-and-mortar retailers that reduced their number of employees working in the store after the initial phase of the pandemic, increased self-checkout, and increased the online purchases of items for pick up. This lack of employees means that many stores are largely unmanned, and shoplifters face little to no human deterrent in the store and can fairly easily walk out with unpaid merchandise.

There’s just no way that these companies can sustain such a miserable retail experience for more than maybe another two years. They will have to evolve or they’ll go out of business.

Shoplifting across the country is up 93 percent since the pandemic. As of mid-2024, Philadelphia saw an average of 426 weekly retail thefts, a more than 20 percent increase over 2023. Early last year, after a five-year period of pausing arrests for retail thefts of less than $500 — and widespread store policies that instructed employees to ignore shoplifting — the city resumed enforcing these laws. According to City data, PPD arrested nine people for retail theft in all of 2024 — and 31 so far in 2025.

Meanwhile, shoplifting schemes are getting more sophisticated, violent and likely to involve multiple people. To address this trend, Philadelphia and suburban police departments are collaborating to bust shoplifting rings. All the while retailers have added Plexiglass locked shelves and security guards — which make for an awful and depressing retail experience.

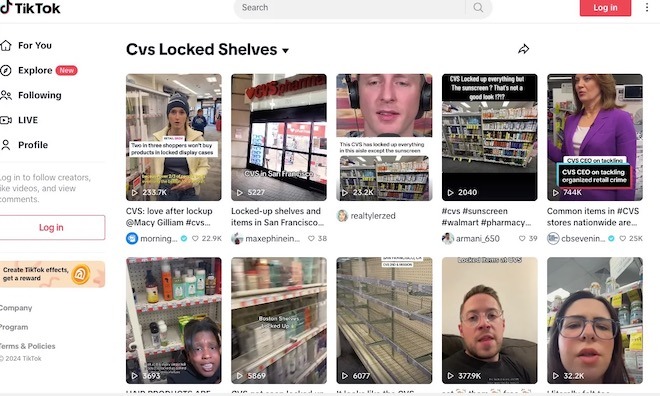

The locked shelf has spawned thousands (millions?) of TikTok and YouTube analyses and parodies. The responses range from humorous frustration to serious concern that these locked shelves represent the downfall of society. To some, the locked shelves are a sign that our cities are decaying and beholden to disorder. They represent the penalty we all pay when a small percentage of people inflict their misbehavior on the rest of us. They illustrate how quality of life issues have become almost impossible to police.

There can be no denying it: everyone hates seeing their stores with locked merchandise.

What should we do about locked shelves?

First, what we shouldn’t do is assign police officers paid for by taxpayers to make up for these retailers’ bad business models. That said, there obviously does need to be some more coordination between the retailers and Philadelphia’s police. Retailers should be paying for private security while coordinating with City police on a strategy to deter shoplifting.

But this kind of coordinated effort should not be done city by city. We should recognize this is largely an urban problem and that groups such as the U.S. Conference of Mayors or National League of Cities should have a sit-down with retailer leadership to strategize. Shoplifting isn’t just a quality of life issue — it’s a brand issue for a lot of cities. It’s hard to convey that a city is safe to live in, visit, or invest in, if people can’t buy shampoo there without unlocking a Plexiglass door.

Third, Philadelphia could try to outlaw Plexiglass on merchandise. Though not without controversy, Philadelphia banned bullet-proof Plexiglass from some businesses in 2017. There is no reason we couldn’t try to expand this effort and make it illegal to put merchandise behind Plexiglass. If businesses no longer can lock up merchandise, these retailers will need to figure out another way to deter shoplifting. At the very least, I think it’s worth pursuing a legislative approach to bring attention to the issue.

Finally, we have to let this play out. There’s just no way that these companies can sustain such a miserable retail experience for more than maybe another two years. They will have to evolve or they’ll go out of business. Simply pushing people to buy things online won’t work — CVS and Rite Aid have far too much competition from Amazon and other online retailers. And yet, with so many vacant pharmacies already filling our commercial corridors, simply letting these stores go out of business is not a good solution either. Maybe this will be a blessing in disguise — an opportunity for chain retailers to rethink what in-person retail can offer in the 21st century.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

MORE FROM THE NEW URBAN ORDER