Last week, I spoke at the Atlantic Festival with Dror Poleg and Jerusalem Demsas on a panel about post-pandemic cities. The Atlantic — like so many publications — has published a lot of content about the urban doom loop, both warning that it may still happen and brushing off the possibility that it will arrive. During the panel, I noted that as we worry about this possible urban doom loop, another, potentially more problematic doom loop is happening before our eyes: the human doom loop. It’s a doom loop that may have equally concerning effects on the economy, safety and urban quality of life.

In many cities, there is the outward appearance that things are back to pre-pandemic normal these days. There are plenty of people on the subway, sold out concerts, restaurants that are hard to get into. But the data tell a different story about how our habits have changed since March 2020. There’s a number of indicators suggesting that life changed for the worse during the pandemic and has remained that way.

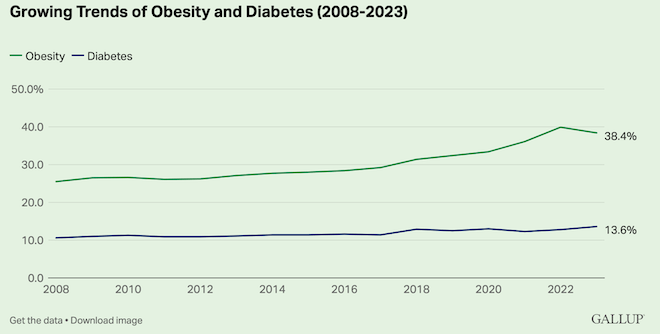

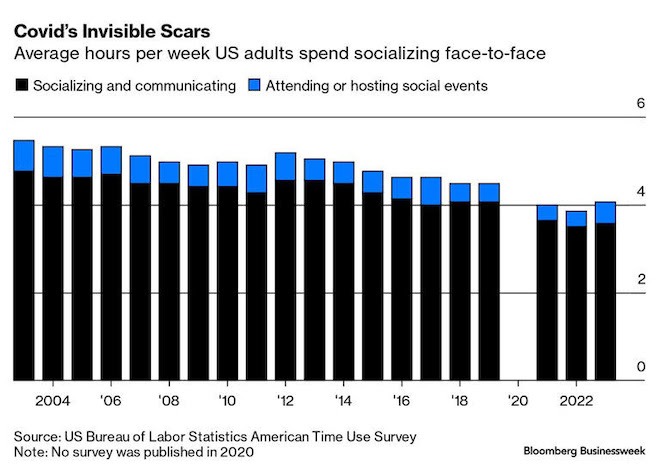

Since the pandemic Americans are:

I think a lot of these negative indicators have something to do with the amount of time we spend alone in our homes rather than out in the community. It’s a trend that has been on the increase since 2003, and has increased the most for people without college degrees. In a Philadelphia Federal Reserve report on time use before, during, and after the pandemic, the Enghin Atalay writes:

For some people and in some contexts, spending a greater share of time alone may improve well-being. Certain relationships — an unhappy or abusive romantic relationship, for example — can be harmful for one’s emotional and physical well-being. A less-extreme example: Some people find mundane social situations a source of anxiety and stress.

However, on average, greater time alone is associated with a decrease in emotional well-being and life satisfaction. The 2010, 2012 and 2013 editions of the ATUS asked about how respondents felt — how happy, sad, stressed, in pain, or tired — during three randomly chosen activities within their time diary as well as their overall life satisfaction. On average, survey respondents who spent a greater share of their time alone reported lower life satisfaction. And activities that are performed alone were rated as less enjoyable.

The reason we spend more and more time at home is because it’s more convenient and less expensive than alternatives like going into the office, going out to see culture and shopping in stores.

But people aren’t just at home doing nothing — they’re likely doing something online.

Digital life and in-person life

It’s impossible to ignore how much more online we are than just four-and-a-half years ago. Amazon’s online sales now account for more than 8 percent of all U.S. consumer retail spending. E-commerce now accounts for more than 20 percent of all sales. Global streaming subscriptions, such as Netflix and Hulu, increased by 22.6 percent to surpass 1 billion global subscriptions in the first year of the pandemic. More than 14 million people use Instacart and 48 million use Amazon Fresh to shop for food.

Digital life and in-person life can co-exist, but there is a bi-directional relationship between the two — the growth of online goods and services are both the symptom and cause of a disappointing physical world. One example of this phenomenon is the way that over the past two decades Uber and Lyft have all but entirely replaced free-flowing taxis in most cities. Taxis were imperfect — often unreliable, unwilling to go to certain neighborhoods, reluctant to accept credit cards, smelly and dirty; the list goes on. But now regular taxis have become so scarce you might go months without seeing one roaming your city. Since people know they can’t hail a taxi on the street, they order an Uber. The cycle is self-fulfilling. And slowly but surely the option to get a taxi without a phone is eliminated forever.

This phenomenon is repeating itself in almost every realm. As people buy more of their goods and services online, there is less quality, practical, local retail in our cities. As more people work remotely, people find there’s no point in coming into the office only to sit at a desk and take Zoom calls. As online entertainment is so abundant and inexpensive, fewer people feel the need to go out to a theater production or see an exhibit in person and more cultural institutions close. As more people manage their online programming to perfection, the less manageable idiosyncratic people seem in person.

The pattern is clear: the more we go online, the less we show up in person. And the less we show up, the less we can expect our cities, and perhaps our physical and mental well-being, to thrive.

That’s the essence of the human doom loop.

The importance of in-person connection

By contrast, research overwhelmingly shows the importance of connecting with people and places in person. Studies show that simply going outdoors is good for our mental health — even helping to ward off dementia. Maintaining routines like a 9-to-5 may also be good for our physical and mental wellness, with commutes providing an important transition and liminal space in our lives. In a world where 15 percent of men say they have no friends, eliminating co-workers who they see and relate to in person on a day-to-day basis makes it that much harder to have friendships.

“Weak ties,” those relationships with a barista or the neighbor at the bus stop, have proven to be important for everything from wellbeing to professional success — and ironically have been shown to matter more for people in digital jobs — but are dying off as stores offer order-by-app, self checkout and drive through.

Demsas asked how I would advise city-makers to improve cities, and I returned to the idea of preventing the human doom loop.

In short, I think the cities that will be most successful in the coming decades will are those that make in-person life irresistible, affordable and easy. Cities that prioritize connection and community in place will reap the social and economic rewards of a happier and healthier population.

Reversing the human doom loop

Here are a few ideas of what they need to do:

- Make it affordable for people to live near amenities. If we focused on making it easier for more people to live near their daily needs without having to drive everywhere, we’d make it easier to show up in person — at work, at cultural activities, and for daily needs like shopping. A recent study shows that people who live in mixed land use areas near transit are more likely to participate in in-person activities. Transit-oriented development is a really old idea, and yet it’s shocking how many communities haven’t enforced or incentivized it.

- Reduce barriers for great retail. It shouldn’t be easier to launch a website than it is to open a physical store, but it’s much, much easier. Cities need to rethink the barriers to quality, interesting retail in their downtowns and in their neighborhoods. That means addressing regulations on small businesses (permits, taxes, etc.), but also exploring the ways that the current market only works for private-equity funded stores or chain retail. If we want commercial corridors worth visiting, they will likely need some curation and intervention. Cities like Paris have created nonprofits to buy or rent out retail and curate those stores. Many neighborhood improvement organizations can do the same.

- Make the in-person choice easy. Drive-throughs are seeing double-digit growth since the pandemic as more people refuse to even get out of their cars to get food and drink. When I was in Detroit, I noticed a lot of shop windows that had fast and easy takeout. They’re essentially like drive-throughs for pedestrians.

There are other ways to make in-person culture easy, such as a program in Philadelphia called Emerging Markets, which brought great performances to farmers markets so people could experience art without having to pay for a night out. Remember when IKEA stores had childcare? IKEA made it easier for people with kids to shop in-person — to actually prefer it — and others could copy that model. There are endless ways in which we could make in-person errands easier and more desirable.

- Consider a four-day work week. Many people who push for hybrid work are those who need extra personal time. It’s clear that the traditional 9-to-5, Monday-to-Friday is problematic, especially for caregivers. European countries by contrast prize a shorter work week, but make the effort to show up in person for work. Some European countries have a shorter work week for caregivers, others for everyone. I think that if parents had one extra day off each week — or firmer caps on the total number of hours worked — the need to work from home would not be as great.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.