Last Friday, the University of the Arts in Philadelphia announced it was closing in a matter of days. The news of this immediate closure came as a shock, with staff and students afforded zero time to absorb the news. But while the timing was very unfortunate, to anyone who has felt the headwinds facing higher education or the art scene, the ultimate end of UArts was not a surprise.

Look around your city at the colleges and universities that are truly struggling — facing declining enrollment, unable to trim tuition costs, saddled with aging infrastructure, specializing in the humanities or centered on religious affiliation. A merger or closure is likely a matter of when, not if.

In 2017, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen predicted that 50 percent of the country’s colleges and universities would go bankrupt in 15 years, or by 2032. Halfway through that time span, that forecast is still outlandish, but a 25 percent reduction in the number of schools is looking quite reasonable.

A scan of 32 colleges in Philadelphia region shows that more than half of them are small, private institutions who are accepting more than two-thirds of their applicants, indicating enrollment struggles. And since this list was last updated, not only has University of the Arts closed, but so has 67-year-old Cabrini College, which is being absorbed by Villanova University. It doesn’t count other recent mergers, including University of the Sciences with St. Joe’s and Philadelphia University with Jefferson University. But the list could get smaller yet: The Philadelphia Inquirer recently ran a story about La Salle University, noting the school’s 28 percent enrollment decline since 2019, sounding awfully similar to University of the Arts’s 44 percent decline in enrollment over the past decade.

Rather than hope something is going to change, cities need to proactively plan for the inevitable future failure or merger of a significant portion of their higher education institutions.

Demographics are destiny

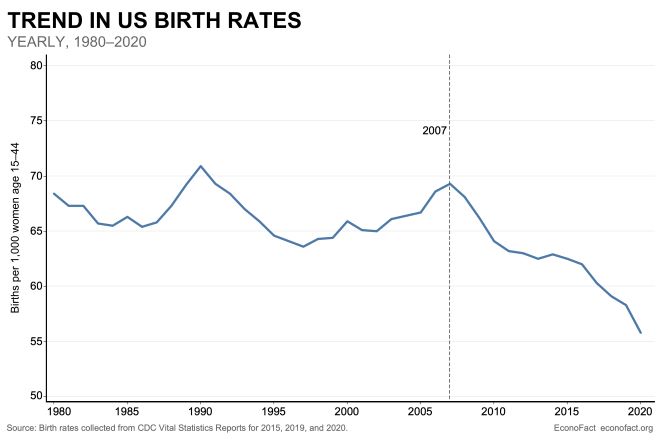

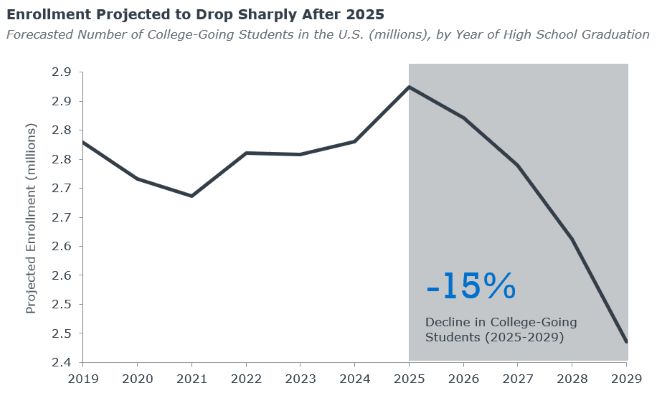

There’s a fundamental issue at stake for these universities: While overall college enrollment has been declining for the past decade, we’re approaching a new tipping point as the children born after the Great Recession of 2008 reach college age in the next two years.

As during all recessions, the birth rate dropped during the Great Recession. But unlike other recessions, this time the birth rate never recovered despite the improving economy. It’s expected that college enrollment will decline by 15 percent in the coming years before plateauing at a permanently lower level.

In addition, now a majority of Americans believe that a college degree isn’t worth the cost. What’s more, the pandemic and the Cold War between the U.S. and China have reduced international student enrollment. All these factors mean that many schools are struggling against big enrollment declines. For states in the Northeast and the Midwest, which have had lower population growth than the South and Southwest and thus fewer regional youth, the situation will be worse.

Grappling with the impacts of college closures

In college towns, these small private colleges and universities are anchor institutions and often the biggest employers in their communities. Their closures can be nothing short of devastating not just to the local economy, but to the local sense of identity as well.

In cities, this weakening of the education sector is also highly problematic, with highly disruptive impacts on jobs, real estate, and most of all, students and faculty. The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) reported on how college closures negatively impact students:

-

- Students who experienced a closure are less likely than students who did not experience a closure to continue enrollment.

- Reenrollment likelihood varies by student demographics and academic characteristics, with students of color, male students and students in certificate programs facing lower reenrollment rates.

- Closure reduces the likelihood of credential completion by almost half for students with no prior credential.

- Completion rates after closure vary by student demographics and academic characteristics, with students of color, male students and older students facing lower completion rates.

In Philadelphia, where we have had an overabundance of both higher education institutions and nonprofits, there is a tendency to see the advantages of nonprofit mergers or closures. Already Avenue of the Arts developer Carl Dranoff is imagining the next era for UArts buildings, one that could be more vibrant than what was there before. Indeed, UArts used its storefront space on the corner of Broad and Walnut for its private cafeteria for years, and a few blocks south one of its buildings had a seemingly inactive ground floor gallery (pictured below). Struggling universities rarely have the time and money to make the most of their physical assets.

But although there may be a more vibrant use for these buildings, it’s likely these buildings will sit empty for years as the school undergoes a messy, slow process of deaccessioning its assets.

Consider the sale of Hahnemann University Hospital a few blocks to the north, following the closure of Hahnemann University. The hospital closed in the summer of 2019; five years later a chunk of its 1 million square foot empire sits empty. While some of its assets were relatively quickly turned into apartments, it took until April 2024 for biotech tenants to move into Race Street Labs, an R&D lab space announced three years ago that occupies just a portion of Hahnemann’s overall footprint.

Cities are already grappling with the crisis of vacant office buildings, and now they’re potentially going to have to contend with empty university buildings as well. All this excess space will put a lot of downward pressure on commercial property values and could encourage more foreclosures.

And empty buildings mean more empty streets. UArts had more than 1,200 students and 700 faculty and staff milling about its campus on a daily basis. While many current students will transfer to other schools in the city, a new crop of students won’t be coming through.

Cities need to keep attracting young people. They’re the lifeblood of the city’s energy, brain power, and creativity. They also spend a much greater proportion of their income than other demographics, whether on food and drink, entertainment, and clothing that are all part of socializing and attracting mates. And unlike families, seniors, and lower income people who all rely heavily on city services such as schools or public housing, young students are generally revenue positive for cities. Eighteen to 34-year-olds are exactly the demographic that cities need to grow, if not at the very least retain. But as schools close, cities may no longer be able to rely on students to boost their population numbers.

Lastly, universities and colleges offer a kind of employment that is too rare in the rest of the private sector. A look at University of the Arts jobs postings shows that a security guard could get a 401K there and hourly wages of up to $28 per hour. In a poverty-stricken city like Philadelphia, anchor institutions are one of the few industries that offer jobs with benefits for people with limited education. The demise of colleges and the wide range of employment opportunities they provide will hurt our lowest-income communities as well.

What cities can do about the crisis of college closures

A New York State senator, who saw Cazenovia College and Wells College close in 2023 and 2024 respectively, recently proposed a bill for technical assistance for municipalities that have experienced a college closure. The bill would provide for assistance on workforce transitions, economic development planning, and disposition of real estate. This kind of technical assistance makes a lot of sense, but when seeing the signs of distress now, shouldn’t our cities and states be approaching colleges before they close?

A New America report, “Anticipating and Managing Precipitous College Closures,” urges communities to take heed of the warning signs before colleges close with limited warning.

These crash-landings do not need to be so difficult. Regulators have often failed to recognize the warning signs or take action early enough to cushion the blow of a closure with protections for students and taxpayers. States, accreditors, and the federal government must all be doing more to understand, anticipate, and prevent precipitous college closures, and to protect students and taxpayers in the event of such closures.

States, cities, philanthropies and major donors have leverage to seek more information before giving money away. Just a year ago, UArts announced a $5 million RACP grant from the State to renovate its student center. In retrospect, this seems like an unfortunate use of public funds.

States and cities that give out grants or other supports to universities could spend more time on due diligence to ensure that the public’s money is well spent and that colleges that are grantees are not at risk of closure. After all, cities and states may be on the hook when colleges close. According to that New America report:

The taxpayer liabilities due to closure can be significant. Among the institutions with the largest amounts of closed school discharges paid out to students — 62 institutions that closed between 1987 and 2016 with over $1 million in closed school discharge liabilities — just six had letters of credit on file, and only one had a letter of credit large enough to cover the entirety of its closed school liabilities.

A simple review of University of the Arts’ enrollment and finances would have revealed some of the problems at hand. Instead of $5 million for a student center, the university could have benefited from support for the work of planning for a closure or merger or a disaster plan in advance. It’s expensive and unsexy work, but incredibly important. While SHEEO believes state state authorization policies should mandate that institutions have contingency plans in place to address potential closures, it seems that donors should withhold support from struggling schools unless they’ve undertaken the administrative work of worst-case scenario planning first.

The key here seems to be anticipating a closure or merger and figuring out a smooth transition. From the perspective of the city, the best outcome seems to be one where student and staff levels are maintained while buildings are continuously occupied. What kind of technical assistance could other struggling arts schools in Philadelphia need? If a school envisions closing or merging in the coming decade, how can these employers get ahead of this crisis by developing strategic real estate plans or training opportunities for the workforce?

As the saying goes, a crisis is a terrible thing to waste. Each of these school closures offers a true inflection point for cities. Maybe UArts closure will provide the venue for the real, hard conversation among local leaders that’s long been needed about the creative economy and higher education in Philadelphia.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.