I know that, as Christmas loomed, your attention was likely diverted by the oligarchical shenanigans of President-elect Musk and, locally, of protestors intent on jamming Center City traffic even after City Council had voted to approve the Sixers’ Market East arena (persuading precisely whom?) — so you may have missed one particular news item from out west. Mat Ishbia, the billionaire owner of the NBA’s Phoenix Suns, modeled for Democrats what their reaction to the cataclysmic election results ought to be. Clearly, he’d gotten the message issued by a fed-up electorate that, despite the nation’s impressive economic indicators, we are in a long-simmering crisis of affordability, and he was determined to do something about it — as if to say to his customers, I hear you.

“Winning starts with our fans,” Ishbia, the 44-year-old CEO and Chairman of United Wholesale Mortgage, posted on X. “When I walk the concourse at games there aren’t food options for families who don’t want to spend a lot of money. That needs to change, so today we’re rolling out our $2 value menu for all home @Suns games.” That $9 hot dog? Now, two bucks. The $8.50 16 oz. Dasani water? Two bucks. The $7 popcorn and $7 bag of chips? Now both two bucks.

“A family of 4 used to spend $98 on hot dogs/water/popcorn,” Ishbia further explained. “Now they can enjoy that same meal for $24. Our fans and community are the foundation of what we do and we will continue to invest in making this the best organization in all of basketball, on and off the court.”

Are you listening, Dems? Five years ago, Annie Lowry of The Atlantic pinpointed the nation’s long-brewing “Great Affordability Crisis:” Unemployment was down, wages were up, and yet if you weren’t in the top 10 percent in terms of income or wealth, it kind of felt like someone was always in your pocket. The problem was most acute in housing, but Lowry made the case that it extended well beyond, and her observations then are, if anything, even truer today.

In the mayor and City Council’s negotiations with the Sixers, they could have made affordability a deal point — at the very least, it would have been smart politics to do so, no?

“The crisis involved not just what families earned but the other half of the ledger, too — how they spent their earnings,” she wrote. “In one of the best decades the American economy has ever recorded, families were bled dry by landlords, hospital administrators, university bursars, and childcare centers. For millions, a roaring economy felt precarious or downright terrible.”

Lowry’s warnings in 2020 went unheeded. And the schism persisted in 2024, with only Congressman Dean Phillips, in his courageous primary challenge to President Biden, seeming to sense the zeitgeist. Not only was Phillips the only Democrat to tell the truth about Biden’s fitness for office, his campaign slogan, in retrospect, spoke to the times better than anything offered anywhere else: Make America Affordable Again.

Instead, Kamala Harris opted for a platform of Democracy, Dobbs and Trump Sucks, while Trump, on the other hand, heralded not taxing tips and Social Security. (Which would further explode the deficit, by the way).

Locally, the Big Squeeze continues; did you see that, post-election, Democrats in Delaware, Chester and Montgomery counties are hiking property taxes by 23, 13 and 9 percent respectively? In Philly, due to a hike in assessments, the average Philadelphian is set to pay $330 more in property taxes this year. (Raising assessments while leaving tax rates stable is an old political trick, essentially a backdoor tax increase.) And water rates are up for a fourth consecutive year.

Cherelle Parker’s $6.4 billion budget is 68 percent higher than Michael Nutter’s and 220 percent more than Ed Rendell’s. In fact, Philadelphia is among the highest-taxed cities in the nation, without a lot to show for the investment. It puts one in mind of the “temporary” Johnstown flood tax, enacted in 1936. It’s now 89 years later and Pennsylvanians are still paying the Johnstown flood levy. I don’t know for sure, but I suspect the cleanup has been completed.

It’s all part of the aforementioned Big Squeeze. Antipathy for Trump’s autocratic ways aside … no wonder multiracial middle-class workers, and those who aspire to the middle class, jumped ship on Democrats or took a flier on Election Day. When a bellwether working class community like Macomb County, Michigan, which voted for Bill Clinton in 1996 and Barack Obama twice, goes Trump’s way by a whopping 13 percent, you’d better pay attention. That’s not just the work of the deplorables.

Sixers as a luxury item?

The rosy argument that inflation and unemployment are down and wages and the stock market are up, while factual, doesn’t square with what folks are feeling, largely because of what Ishbia has observed and what Lowry put her finger on four years ago. If you’re a middle-class dad, taking the wife and kids to a Sixers game seems like a luxury, even though the Sixers don’t stack up as badly as some when it comes to affordability.

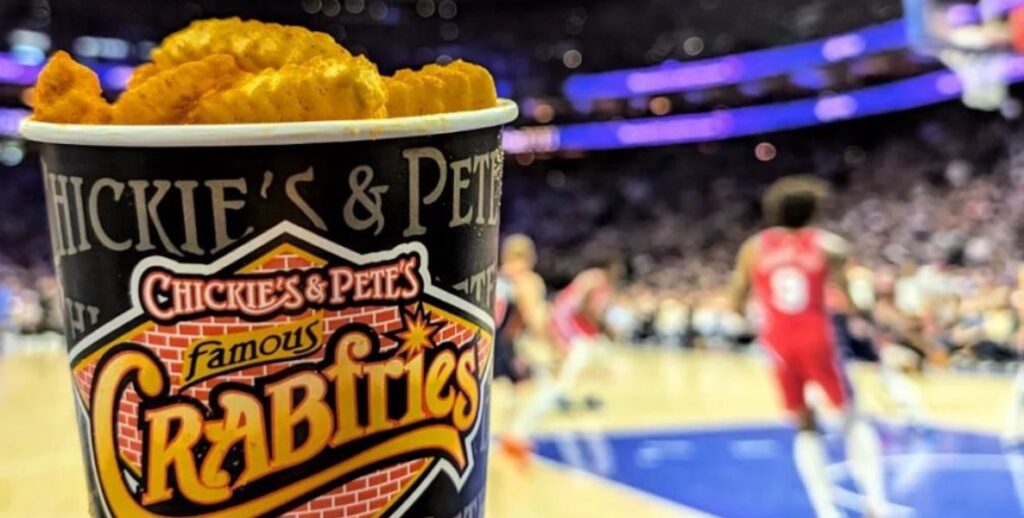

According to bookies.com, ours is the 13th most costly of the NBA’s 30 teams for a family of four — $291.96, comprised of the cheapest seats in the house ($210.77); parking ($20.85); two 16-ounce beers ($21.34); two 20-ounce sodas ($15), and four hot dogs ($24). Beer is a particular strong suit of ours — we’re the ninth cheapest. And, by the way, if you’re looking for another reason to hate the Knicks, other than their playoff dismissal of us last season, look no further than their league-leading price tag of, gulp, $745.

I’ve long cheered for supply-side growth; the cities that flourish are the ones with cranes in the sky. But part of government’s role is to manage development and make sure it aligns with the common good. In the mayor and City Council’s negotiations with the Sixers, they could have made affordability a deal point — at the very least, it would have been smart politics to do so, no? To say, we’ll greenlight this project, but we want to see a plan to make your product more affordable to more Philadelphians. And acceding to that request would have been great public relations for the Sixers, no?

A city is nothing if not an experiment in shared experience that breaks down walls between rich and poor, young and old, and Black and White; that’s what a sports arena — properly constructed and led with civic values — can do.

That’s what it was more than a quarter century ago, when then-part owner, team president and civic cheerleader Pat Croce unveiled his $76 Special promotion: four upper level tickets, four hot dogs, and four sodas — all for $76. Yes, Croce was a master salesman and those high-price luxury boxes quickly filled up, drawn by the jaw-dropping on-court exploits of Allen Iverson. But offers like the $76 Special also communicated to the city that his team was not just his, that it was really for everyone.

Another way for Parker and Council President Johnson to have struck that note would have been to make a public ask for the team to move its operations back into the city limits. After all, when it left for Camden thanks to overly generous Jersey tax credits in 2016, it took roughly $2 million per year in wage taxes out of the city coffers. That’s not a lot when it comes to a $6.4 billion budget, but making an issue of it would have been symbolically meaningful — an act of local populism, if you will, proof that your government was intent on making this civic asset accessible to all of us.

Perhaps Ishbia’s new menu in Phoenix plays to my sentimentality; maybe I’m wedded to a past that can never be again. When I was a kid, after all, my dad would come home from work at 5pm on a Friday night and say, “Hey, want to go to a Sixers game?” Down to the Spectrum (RIP) we’d go, on a whim. The team was historically bad — 9-73 in 1972, but to my 9-year-old eyes, Fred Carter and Leroy Ellis were far from losers. Dad would pay 12 bucks for floor seats. I remember being close enough to see sweat pouring from the headband of the Lakers’ Wilt Chamberlain, like his head was wringing it out. Everything about the experience was shared with my fellow Philadelphians, from our laughter at PA Announcer Dave Zinkoff’s comic whine to the halftime jostling in the smoke-filled concourse. There were something like 12 luxury boxes in that building, compared to 126 in what would become the Wells Fargo Center; there were no separate entrances for the aristocracy, so everyone shared this same public space.

One time, Sixers star (and future coach) Billy Cunningham led a furious rally to close out a first half. Maybe there were 8,000 people in the stands, but when we all rose as one to cheer, to hug and slap each other five, I remember looking around, taking it all in. I know now it was my first introduction to Communitarianism — the idea that we really are all on the same team.

This is what, out west, Mat Ishbia seemed to intuit from his walks around his increasingly stratified concourse. A city is nothing if not an experiment in shared experience that breaks down walls between rich and poor, young and old, and Black and White; that’s what a sports arena — properly constructed and led with civic values — can do.