The murder of police officer Robert Wilson III on March 6 reminds us we live in a city where gun violence is still all too common. Officer Wilson walked into a store to buy a gift for his son. Sadly, he also walked into a robbery by two guys with long rap sheets.

He died a hero, making sure other customers were out of the line of fire. His heroism is a sad reminder.

This is the first Mayoral race since the early 1960’s that public safety is not a major election issue. We need to change that.

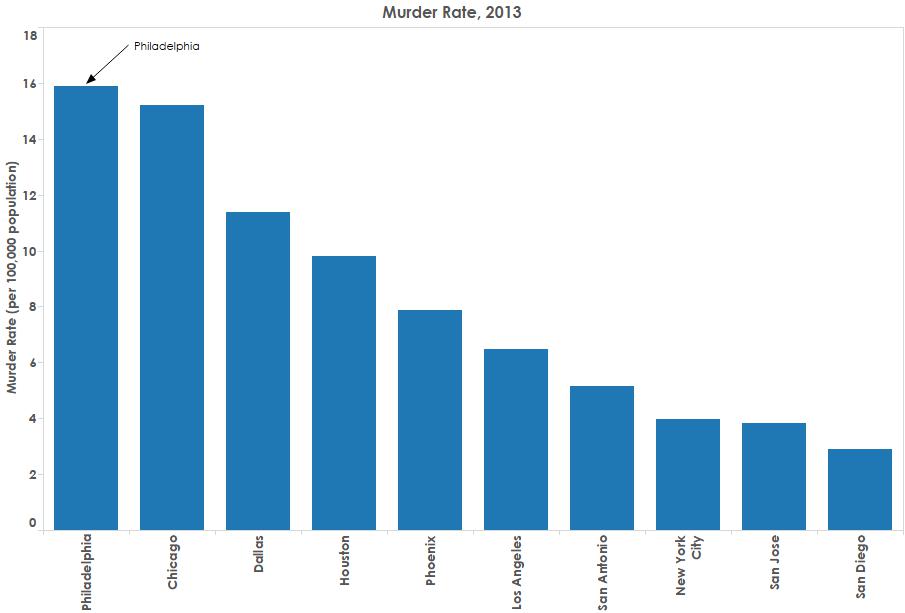

Philadelphia is the most violent of the ten largest cities in America. While Chicago gets national press for gang killings and children caught in the crossfire, we have a statistically higher murder rate. Compared to a New York City resident, a Philadelphian is four times more likely to be murdered.

Yes, we have a high poverty rate. But differences in poverty rates alone do not explain the variation in violent crime. New York City’s poverty rate is only a few points lower than Philadelphia’s.

Why aren’t we talking about crime in this campaign? There are three reasons.

The first is our recent success in reducing crime. The past two years show crime rates lower than any time in recent history. Mayor Nutter has kept his eyes on those numbers and deserves some credit. But a few years do not make a long term trend.

Philadelphia is the most violent of the ten largest cities in America. We have a statistically higher murder rate than Chicago. Compared to a New York City resident, a Philadelphian is four times more likely to be murdered.

Second, we have a popular police commissioner and a popular district attorney, the two visible symbols of criminal justice. Chief Ramsey is the best chief since John Timoney. Seth Williams is an independent-minded breath of fresh air for a department that was once a stranger to data and strategy.

Third, other issues, most notably education, have taken center stage. A school system in fiscal distress that is actively seeking more money from the state tops our priorities, much as it did during the Governor’s race.

But we can do much better than we are in terms of reducing violence. Two important interventions – GunStat and Focused Deterrence – that got off the ground in 2012 and 2013 have yet to reach full potential. This has to be a focus for the next administration.

A bit of context here: The greatest change in urban governance since the early 1990s happened in public safety. There was a two-part innovation: one related to re-norming public life, and a second related to using data to make policing and prosecutorial interventions smarter.

By re-norming I refer, in part, to the “Broken Window” ideas that had its roots in the work of George Killing and James Wilson. Their claim was that by addressing lower levels of disorder a city creates an atmosphere where lawlessness is less likely to occur, and signals to its citizens what kinds of behaviors are acceptable in a civil society.

The use of data in police work received a huge boost with the introduction of geocoding and spatial analytics. New York City under Police Commissioner William Bratton in the 1990’s adopted CompStat, a data driven approach to crime prevention that went as viral as any policy innovation could. Bratton adapted the idea from a transit cop who worked for him named Jack Maple. He saw Maple’s success using data to identify hot spots for crimes, directing resources based on patterns he saw, and demonstrating significant effect over time.

Today people are used to a safe New York City subway system but in the 1970’s and 1980’s it was anything but. In many ways, the revitalization of New York City was rooted in first making public transit safe. It increased everyone’s 24-hour mobility and access. It opened up the city.

But CompStat was always more about management techniques than loading data onto maps. It is one thing to have data and another thing to use the data to make decisions and keep people accountable for improvements over time.

The change in how we think about public safety and policing (first in New York City and then elsewhere) was dramatic. We went from thinking that the function of policing is only to respond to crime after it occurs, to viewing policing as a crime prevention and reduction system.

What seemed inevitable throughout the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s – the rise in street crime – was no longer so.

Philadelphia has had a data focused crime strategy since the days of John Timoney, who came from the NYPD. But the use of data to make decisions and hold district captains accountable atrophied under Commissioner Sylvester Johnson, who followed Timoney.

A long time member of the Philadelphia Police Department, Johnson was an inside guy used to the old ways of policing. They did not always work. Murder rates and gun violence went up again until 2006, when they began to gradually recede.

A newly elected Mayor Nutter pledged that the number of murders would decrease more dramatically. We may forget now, but it was central to his campaign in 2007. After he was elected Nutter brought in Charles Ramsey from Washington DC to become police commissioner. Ramsey released a thoughtful strategy in 2008 and the numbers continued to decline until 2010.

The murder rate began to move up quickly in 2010 through 2012. This is when a host of new initiatives got underway. In 2011 local officials began to increase coordination around gun violence which led to an inter-departmental program (Police Department and District Attorney’s Office) called GunStat.

GunStat has been described as GPS for tracking repeat offenders who use firearms. Hotspots for gun violence are identified and a focus is placed on removing previous offenders if they commit another crime.

GunStat works on the theory that a very small number of people commit a very large number of violent crimes in a relatively contained area. More importantly it works on the theory that we have the information through the offices of the DA and police to allow us to target resources where they are most needed. We just have to do it.

When GunStat worked best there were ongoing meetings and coordination between the police and DA but, lately, that has not always occurred at the level we need. Still, GunStat appears to be one of the initiatives that has helped move the data in the right direction. Clearly the DA’s office has embraced it and continues to work with police districts to move the ball.

Following the implementation of GunStat there was another, potentially even more important initiative launched: Focused Deterrence. The brainchild of David Kennedy, a professor of criminology, Focused Deterrence has been hailed as the single most important program to bring down the murder and violence rates in Boston. It is now being implemented in a variety of cities around the country to great success.

A program called Focused Deterrance brought down the murder and violence rates in Boston. A pilot program here hasn’t had the muscle needed from the Mayor’s office. The Deputy Mayor for Public Safety does not control resources, nor as the pols say, does he have the political juice.

The idea is deceptively simple. The police, DA, and social service agencies work together to generate a list of those young people most likely to be in danger of committing serious crimes. Using gang affiliation information, arrest data, and social service information, at-risk teenagers and adolescents are brought together for a meeting with city officials.

At the meeting they are told what will happen to them if they continue to move in their current direction or they are offered social service assistance to move in a different direction. This approach has been tried since the middle of 2013 in one section of South Philadelphia with dramatic results. Of the first 103 young people brought in, 25 turned their lives around. The result showed up in the crime data.

I first became aware of GunStat and Focused Deterrence when Bryan Lentz, a former Iraq war vet, a one time State legislator, and a former prosecutor with the Philly DA’s office (now in private practice) explained it to me several years ago.

Lentz is an advocate for data driven approaches to fighting crime. The former chief of the Philadelphia Regional Violence Task Force, he views the integration of policing, prosecution, and social services as critical to bringing down rates of violence. He has seen it work.

Everyone I spoke with seems to think that Focused Deterrence in South Philly was a success and could be expanded throughout the city. But we are not doing that. I followed the good press it got from the Inquirer in 2013, but today it seems to have fallen through the cracks.

Here is what seems to be happening. In the case of Focused Deterrence, we have not had the muscle needed from the Mayor’s Office to provide the budget incentives and high level directives to keep coordination going and make sure a successful pilot is expanded. The Deputy Mayor for Public Safety does not control resources, nor as the pols say, does he have the political juice.

The next mayor cannot assume that the rates of violence and murder will go down year after year. It takes focus and a data driven strategy. And it takes strong leadership across multiple agencies and domains.