Four years ago, the election for mayor in the fifth largest city of America was relatively devoid of substance, and amounted to a coronation of Jim Kenney. After the first of three debates between the candidates in 2015, I took NBC-10 and moderator Jim Rosenfield to task for asking mostly inane questions, like “Yes or no: Philadelphia has a race problem.” Somewhere, I wrote, Lincoln and Douglas were gyrating in their graves.

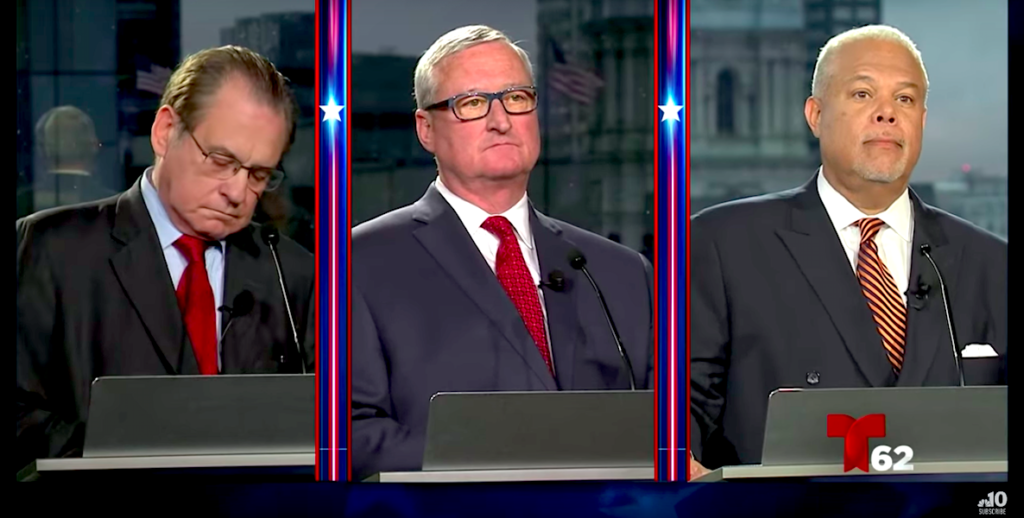

Alas, up until now, this year’s campaign had followed a similar script. It’s been downright Seinfeldian—a campaign about nothing. Incumbent Kenney, up in the polls and newly flush with $1 million from Michael Bloomberg’s pro-soda tax independent expenditure PAC, has predictably played the old Rose Garden game, rarely emerging from City Hall to give his challengers, Tony Williams and Alan Butkovitz, a chance to be seen as his equal.

Last week, Kenney bailed on two debates, which is why Williams sarcastically thanked him for showing up last night. Politically, Kenney’s peek-a-boo defensiveness is the smart strategy; Kenney is a shrewd, if cynical, political operator. But a city with challenges like ours—the worst poverty and highest tax burden in the nation, an exploding murder rate—deserves a full-throated debate. And, last night, NBC-10 and Jim Rosenfield gave us one.

At least last night there was a debate on what matters in our public life, and where we ought to go, which we haven’t had in mayoral reelection campaigns for quite some time.

With the exception of a few absurd yes or no questions at the end, the candidates were consistently challenged to lay out specific plans. Kenney was on his heels much of the night, clearly not happy to be sharing the stage with his challengers, who he’d recently dismissed as “gnats”; Williams came off as quick on his feet, well versed in policies that work elsewhere, and carried himself with a mayoral air, while Butkovitz was pugilistic and fiery, relentlessly calling attention to Kenney’s dissembling.

Most importantly, real differing visions emerged on issues ranging from taxes and spending to law enforcement and housing. Williams called for a state of emergency for homicide, and referenced an app in St. Louis that enables residents to identify a live shooting and summon police with one click. Kenney, when pressed on the poverty rate which has remained unchanged since he took office, rosily predicted that his investments in education would result in a 10 percent decrease, calling it an “aspirational goal.” Williams took issue with that, also rosily pledging to name a Cabinet-level poverty czar charged with cutting the rate in half in eight years. For his part, Butkovitz talked about taking a page from the environmental movement and including in the zoning and planning processes gentrification impact statements, so city officials know ahead of time what projects are likely to cause displacement.

Watch the debate

Perhaps the star of the evening wasn’t the candidates or Rosenfield, but one of the questioners, the Inquirer’s managing editor for opinion Sandy Shea, who seemed to stump Kenney with a very fundamental question, which she had to ask twice, seeking the “metrics you’re using to measure the success of the local School board versus a state Board?”

![]()

You’d think this would have been a softball for the Mayor. Instead, he stumbled: “I think the improvement in the child’s, the improvement in the child’s work is what we’re going to judge the Board on,” he said. “If the children are doing better and getting higher test scores and graduating at a higher rate, that’s how we judge the Board. I also judge the Board on their interaction with us, because we’ve tried to take all the city departments that touch the schools, and it’s almost every one, to help them get their work done.”

Butkovitz promptly called Kenney out for bragging about all of a 1 percent increase in the graduation rate in 2018, to 69 percent, 15 percentage points below the national average. But there was a bigger, more nuanced critique to be made: The question concerned metrics used to evaluate a governing body, and Kenney’s response touched not at all on governance. Test scores and graduation rates, after all, are the metrics by which the Board judges Superintendent Hite, but aren’t there metrics that apply specifically to a local Board? Fiduciary responsibility? Rooting out a targeted amount of waste by a certain date? Hiring more and better principals and teachers, and reforming the ways in which they’re judged?

By asking for specific metrics, Shea had revealed a flaw that’s often characterized Kenney’s administration: A steadfast refusal to attach objectives, specific goals and timetables to policies, lest you fall short.

By asking for specific metrics, Shea had revealed a flaw that’s often characterized Kenney’s administration: A steadfast refusal to attach objectives, specific goals and timetables to policies, lest you fall short. (The soda tax, which Kenney touts as his premier accomplishment, is said to be funding Pre-K. But have you been shown a projection for return on that investment? Have you been told, for instance, that in the next decade the graduation rate should jump by, say, 5 percent as a result of this expenditure? Kinda would be nice to know what you’re paying for, no?)

Shea also got the biggest laugh of the night, while Butkovitz was tearing into Kenney, and Kenney started sniping back, over who was more tainted by taking money from indicted labor leader John Dougherty, which all had done. “Sandra has a question for us,” Rosenfield intoned, trying to restore order.

“Uh, I don’t know, I think I’d like to watch this,” Shea deadpanned.

But, ultimately, the winner last night wasn’t Shea, Rosenfield, or the candidates. In a town with far too little real Democracy, the winner was the voter, who could tune in and, at least for an hour, hear serious questions and mostly smart, thought-out replies from those who would lead us. Sure, we’re likely to have an embarrassingly low turnout next week at the polls. But at least last night there was a debate on what matters in our public life, and where we ought to go, which we haven’t had in mayoral reelection campaigns for quite some time.

Come to think of it, why do we only hold debates every four years, connected to elections? Why not go on local TV and subject yourself to queries from the likes of Rosenfield and Shea throughout your term? If, as expected, Kenney wins reelection, how about this challenge: Let’s hold a series of public discussions—we don’t have to call them debates—about ideas that can move the city forward every few months. You, Mr. Mayor, on a stage with other pols, thinkers, and thought leaders, hashing out the issues of the day in front of a live audience? In other words, let’s try a little Democracy, in the American city where it was born.