About five years ago, I was asked to moderate a series of private, off-the-record dinners between a roomful of uber-successful CEOs, entrepreneurs and civic leaders. As I often do in this space, I took the opportunity to urge those who had already done so well to widen the aperture of their lens, to go from focusing on their own good fortune to leading the way toward real change that hews to Philadelphia’s common good.

After all, I’d argue, a recent World Bank study had found that, globally, free enterprise had lifted a billion people out of poverty over the last decade. In other cities, business and civic leaders, rather than deferring to a sclerotic political class, often punch above their weight. New York, for example, was saved from bankruptcy in the 1970s when the business elite stepped forward and, en masse, paid some $600 million in taxes—in advance.

The argument, for me, is always a bottom-line one. Combatting inequity actually is smart business, an idea advanced by none other than Henry Ford, who insisted on paying his workers enough that they could afford to also be his customers.

At one of those dinners, a slight, bespectacled, wired ball of energy rose to make a different kind of argument: a moral one. It was Dr. Steven Klasko, the disruptive president and chief executive officer of Thomas Jefferson University and Jefferson Health. He’d just read a stunning statistic in the New York Times, attesting to the 20-year life expectancy differential between primarily white residents of Society Hill and the mostly minority denizens of Strawberry Mansion.

I’ve said this before—one of the things we need is radical collaboration. I’ve spent 30 years in Philadelphia. It’s been one of the real detriments here. We really don’t have radical collaboration.

This was well before the execution of George Floyd, and years before terms like “equity” had entered our popular lexicon. Yet here was this voluble CEO in a bespoke suit, his outrage palpable, passionately urging other Masters of the Universe to do the right thing and warning them that if combating inequality did not become a priority for this room, all of our futures would look very bleak.

I flashed back on Klasko’s heartfelt oration this week, when he and his team announced Closing The Gap, a $3 million Jefferson collaboration with Switzerland-based Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. that will focus on five zip codes that are home to some 200,000 Philadelphians at extreme risk of cardiovascular disease. It is nothing less than a reconsideration of what we think of as the delivery of health care. Instead of waiting for patients who are essentially ticking time bombs to find their way into hospital emergency rooms, Klasko will be sending out street teams of physicians and educators to go where the patients are, from barbershops to church basements to home living rooms.

It’s an effort in keeping with Klasko’s “health care at any address” mantra, and consistent with other bold moves the CEO has made, like the establishment of The Philadelphia Collaborative for Health Equity, and the Frazier Family Coalition for Stroke Education and Prevention, the result of a $5 million donation from Philly native Ken Frazier, the recently-retired CEO of Merck & Co, and his wife Andrea.

And Klasko’s not done yet. In the coming weeks, details should emerge about the long-debated and planned merger between Jefferson and Einstein hospitals. At the end of the day, Klasko just may end up presiding over Philadelphia’s largest health care system, at a time when so many others in his industry are retrenching or downsizing.

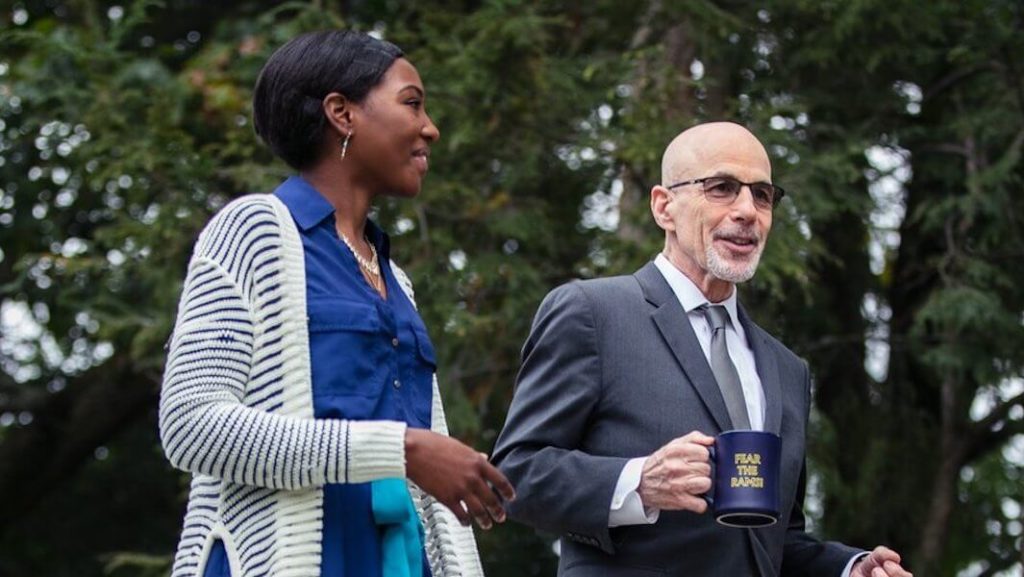

This week, I caught up with Klasko for a wide-ranging conversation. What follows is an edited and condensed transcription.

Larry Platt: If I’m a patient, how will I interact with the Closing The Gap program?

Steve Klasko: If you’re a patient in one of these zip codes, it will be like a political campaign. A lot of those who are most at risk of cardiovascular disease are males, so we’re going to be looking at where are you on Saturdays and Sundays? We’ll meet you in the barber shop. We’ll find you at church. We’re going to ask if we can meet you at home. We’re going to work with Comcast and Verizon to get you broadband. We’re going to try and understand, if Comcast offered you free broadband, why didn’t you take it?

We’re going to sit down with you and your family if you’ll allow us to, and if you tell us, “Well, the only place I can go to shop is a bodega that sells Fritos and I wish I could get healthy food,” we’re going to work with companies to figure out how we can drone deliver or Instacart healthy food to you. We’re going to work with Congressman Dwight Evans and others to enact enlightened health policy that says if you’re willing to serve your family healthy food we’ll get you 20 percent more in government assistance in food, and we’ll Instacart or drone deliver it to you, eliminating that food desert.

And why target cardiovascular disease? Because it’s 100 percent treatable and 100 percent preventable. It’s all food, all getting on cholesterol drugs at the right time, all exercise. You can educate people starting at home—almost none of it has to do with what happens at the doctor’s office or hospital.

LP: I’m among those often championing our region’s “Eds and Meds” as a singular success story, but you’ve cautioned me in the past to temper my optimism about the sector with some tough love realism. Can you explain that?

SK: I think it’s a little bit like you can’t really help your alcoholism unless you admit you’re drinking too much. And one of the issues in Philadelphia has been we spend a lot of time patting ourselves on the back for the things we tend to do well and we tend to say there’s nothing we can do about the things that we don’t do well.

Why target cardiovascular disease? Because it’s 100 percent treatable and 100 percent preventable. It’s all food, all getting on cholesterol drugs at the right time, all exercise.

Look, based on my background and culture, I just kind of wake up feeling guilty every morning just for the hell of it. But we are one of the poorest cities in the country. That’s just a fact. And we have some of the best Meds and Eds in the country, with Penn, Drexel, Temple, Villanova, Jefferson. That’s also true. So when it comes to health, you’d think those two things would kind of come together, but it hasn’t.

Here’s a statistic for you. Down in Atlanta, there’s a company called Sharecare, a health and wellness company that provides consumers with personalized data and programs to improve their health. It was founded by Jeff Arnold, the founder of WebMD, and Dr. Oz. Arnold told me that, “Despite having five great academic medical centers in Philly, you’re 48th out of 50 metro areas for health for people of color.”

So I made a commitment four years ago to stop talking about that equity gap and start actually doing something about it. We created the Philadelphia Collaborative for Health Equity and it meant a few things. It meant that starting in 2016, 25 percent of my personal incentives were around health equity parameters in Philadelphia that have nothing to do with Jefferson.

LP: Wait, so you asked your board for that?

SK: I did. I said, Look, if we’re going to have a mission that says we improve lives, not just me, but some of my other senior members, we have to have a say in that. Every place has a gala, right? And they give away, like, a puppy for $50,000. It’s like, give us money so we can get a bigger proton than the next guy. Well, our last 3 galas have been for health equity issues and it’s been a game changer for us.

Under the Collaborative, we founded the Frazier Family Coalition for Stroke Education and Prevention. Talking to Ken, he’s said he wants the next phase of his life to be about making a social difference. He said, “Where I was born, at 18th and York? As an African American man, if I still lived there I’d have a 35 times greater chance of having a stroke than where I live today in suburban Philadelphia. Nine miles away. Four miles either way of the Rocky statue—I can run both ways—a 30 times chance.”

So he said, “Steve, your Health Care At Any Address model means you’re one of the few people who understands what I’m about to tell you. I want to make a difference and I’m going to give you $5 million to start and I want it in the community.” He drew a little circle around where he was born at 18th and York and said, “I want it somewhere there.”

Well, one of our development folks said, “Hey, that’s in Temple’s territory.” Since it’s not the Jefferson Collaborative, it’s the Philadelphia Collaborative, we called [former Temple Provost] JoAnne Epps and gave Temple half the money, looked at what our assets are and what their assets are, and created a collaborative program.

We looked at that circle Ken drew around where he grew up and, you remember that dinner meeting where you first heard me speak? It turns out the real estate developer who arranged those dinners, Mark Nicoletti, owns a strip mall there and believed in what we’re doing and gave us 20 years of free rent. So you talk about the bright side of Philadelphia? The Frazier Family Coalition is now a Temple-Jefferson partnership, and it’s funded by a Philadelphia native who really wants to make a difference, but wasn’t just willing to do the usual bullshit of giving money and letting you do whatever you want with it. No, it was: I want it near where I grew up and I’m going to hold you accountable.

LP: You know, you mentioned that you reached out to Temple and split the Ken Frazier grant with them. That sounds like a very un-Philly gesture. Partnership and collaboration isn’t often the default move here. Tell me about that.

SK: We were already negotiating with Temple, because we were going to acquire their share of Health Partners Plan and we talked about Fox Chase before the pandemic. So the good news is we had a reason to have board chair and board chair get together, a reason for [then-President] Dick Englert and I to get together. You get together for a drink and it might be about a transaction, but by the second glass of wine, you’re saying, You know, it really sucks that we haven’t been able to solve this health equity thing, and you start talking about that and you realize it has nothing to do with our competition, and you say We should talk about what we could do together.

We are one of the poorest cities in the country. That’s just a fact. And we have some of the best Meds and Eds in the country, with Penn, Drexel, Temple, Villanova, Jefferson. That’s also true. So when it comes to health, you’d think those two things would kind of come together, but it hasn’t.

So we made a decision on the philosophical side that we were going to create a group to talk about how Temple and Jefferson could work together, across all four of our pillars: Academic, clinical, innovation and philanthropy. I’ve said this before—one of the things we need is radical collaboration. I’ve spent 30 years in Philadelphia. It’s been one of the real detriments here. We really don’t have radical collaboration.

We flirted with it during Covid, but I’m not sure that will last. We certainly didn’t show it when Hahnemann Hospital closed. We had cliques of radical collaboration versus cliques of radical competition—you guys reported it. There was the Klasko-led collective and the Fry/Hilferty-led collective. Well, why? If we’re talking about residents, if it had been a collective of all of us, we would have kept all those resident physicians in Philadelphia. We wouldn’t have been in court talking about which one was going to give more money. So I think we haven’t broken that. There aren’t many things where Penn and IBC and Jefferson work together, and we all deserve some of the blame for that—I certainly haven’t done all I could.

LP: New leadership is emerging at a number of institutions, including at Penn and IBX. Does that make you optimistic about the chances for more collaboration in the future?

SK: I’m optimistic that there’s a chance. We’re a bit of a driver for change. The sum total of the Einstein merger, what we’re doing with Novartis and our work with venture capital firms like General Catalyst means we’re going to wake up and be the first or second largest employer in southeastern Pennsylvania, with 40,000 people. I think for people who know me, they know I’m not a wallflower, we’re not just going to keep doing the same old thing.

So the question becomes not about us, but do other people view that as a threat or as an opportunity? I would hope a Penn or an IBC would see it as an opportunity. That they’d say, Boy, look at what Jefferson and Temple did together. Jefferson is clearly in a different place, with Einstein. How can IBC and Jefferson work together? How can Penn and Jefferson work together? That’s one way it can go. Another way it can go is that Jefferson is seen as this juggernaut that needs to be tamped down, which would be, in some respects, the normal Philly way to do it.

But I’m optimistic because I’m an optimistic guy. And everybody involved is a great person. I believe that [IBX CEO] Greg Deavens, [University of Pennsylvania Health System CEO] Kevin Mahoney, certainly [Temple University Health System CEO] Michael Young, and [Main Line Health CEO] Jack Lynch all believe in this stuff.

So I think there’s a chance. One would hope there would be more of a push from the city and state to encourage all of us to start to say how we can work together to really solve these problems without having to say who’s on top and who’s on bottom, without asking is this an IBC initiative or a Jefferson initiative.

I’ve gone to the governor and I’ve gone to the mayor and said, “If you guys were smart, you wouldn’t give a cent to Penn or Temple or Drexel or Jefferson or any of us for this. You ought to put a lot of money to solve this problem into the center of a poker table and say to us, Okay, you guys come in together and get that money. Steve, you don’t want to be part of it? That’s great, but then you’re not going to get any of this money to solve this problem. We need something like that.

LP: What has been the response to that?

SK: Everybody thinks it’s a good idea. It’s the same response I got when I went to the Trump team and to the Biden/Harris teams and said what you really need is a 9/11 commission for health care. Everybody thinks it’s a good idea, but it doesn’t seem to go anywhere.

To me, it would be a game changer to have a mayor say to all of us, We’re failing guys, so I don’t want to hear from any of you. When the five of you are ready to come together and tell me what you need— not what Penn needs, not what Temple needs, not what Jefferson needs—and what you’re willing to commit to when it comes to outcomes, I’ll be happy to have that conversation.

I don’t think anyone’s actually against that. They just don’t think like I do. I wrote an article for Modern Health Care called “Do We Need a Greta Thunberg in Healthcare”? I’ve always said that if you want to see the future, find good people who are uncomfortable with the status quo. Well, the thing about Greta Thunberg is, as annoying as she might be to some people, she challenges the status quo. We need everyone in Philadelphia’s health care industry to use the Temple and Jefferson partnership with the Frazier Family Coalition as an example, and we need everyone to say I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore.

LP: Shout out to the movie Network. Let’s explore your different style of thinking. Earlier, you explained your passion for health equity by saying you wake up every day feeling guilty. What did you mean by that?

SK: Obviously, being Jewish and having your Jewish mother tell you that everything you did you should feel guilty about, that played a role. But it’s interesting. A lot of people say to me You’re very different from most health care CEOs, who are risk averse.

A lot of it is how I started—remember, I was a private practice doctor in Allentown, Pennsylvania. The chances of my being an assistant professor at Jefferson, let alone its president, was 0.0 percent. And in fact everybody I knew is still delivering babies in Allentown. Why aren’t I? For whatever reason, I have a brain that just sees bullshit.

Back when I was in private practice, 97 percent of ob/gyns were male, and the number one performed procedure was hysterectomy and the number two was c-section. I happened to be at a Penn State lecture and I remember this very old male ob/gyn—probably my age now, actually—and he said, “Look, if you see a small fibroid, just take out the uterus, because after a woman has children she doesn’t need her uterus.” I didn’t think much about it. That was the culture back then.

But then I was at Barnes and Noble and three of the top 10 nonfiction bestsellers were What My Hysterectomy Did to Me, The Hysterectomy Hoax and How a Hysterectomy Ruined My Life. So—I don’t know why I’m wired this way—90 percent of people would say, Oh, that’s curious, let me go back to delivering babies and doing hysterectomies at Allentown Hospital. But I was up that night ‘cause that really pissed me off. And so I left my private practice and did some work on the psychological and sexual effects of hysterectomies, and that became a defining moment for me.

I left a very comfortable position for a very uncomfortable position. And that sort of defines every job I’ve taken—people have told me not to take them. Same thing happened in the 90s, when I’m listening to really smart doctors saying business is killing us, insurance is killing us. I’m thinking I can deliver a pretty big baby through a relatively small opening—surely I can figure out this business stuff. So I went to Wharton, got an MBA and had the epiphany that has driven me ever since.

My campaign the last 20 years has been how do we get docs to be more creative? ‘Cause if you’re more creative, you’re more willing to accept change in a changing environment. My research the last 20 years has been looking at how we select and educate doctors. And it’s asinine to keep selecting doctors based on science GPA and organic chemistry grades and somehow be amazed doctors aren’t more empathetic. Instead, we need to choose doctors based on self-awareness, empathy, communication skills and cultural competence.

LP: What is the book you’re writing now about?

SK: The more I’ve thought about fixing healthcare, the more it hit me that if, during the Industrial Revolution, we had thought that the combustible engine would cause climate change, we might have made some tweaks. If we had thought during the agricultural revolution that the corn-based economy would cause childhood obesity, we might have thought differently. And certainly if we had thought about the social media revolution, we probably could have figured out that we were creating ways to spew hate.

So the book that I’m working on now is the recognition that there’s a 100 percent chance that the fourth Industrial Revolution of AI, drones, genomics, and continuous data can be great and the equally 100 percent chance that it will be devastating, and we’ll have congressional testimony 10 years from now if we don’t put ethics in at the beginning.

Amy Abernethy, the former deputy commissioner of the F[ood] and D[rug] A[dministration], and I have been leading a project with leaders across the country around putting guardrails on the fourth Industrial Revolution. Once everybody has my genomics, what’s the chance that Google won’t use that for bad purposes?

Big tech is not going to solve this. It’s going to take a coalition of the willing. That’s what my talk is now—it’s called Is There An Avatar in the House? From Covid to Consumerism. How do we make sure the fourth Industrial Revolution will be done in a responsible way?

LP: You often say that Jefferson is a top academic medical center that’s willing to think like a startup company. But with all your growth—particularly when the Einstein merger goes through—how do you maintain that upstart culture?

SK: It’s hard. We really have to work on it. When I got here in 2013 I talked about the old math—in-person tuition, in-patient and outpatient revenue, and NIH Funding. One faculty member said, “Hey dude, that’s our entire math.” I said, “Yeah, but it’s not going to be good math forever. The new math is going to be innovation, digital transformation, strategic partnerships, and philanthropy.” It was a shameless rip off of Steve Jobs—I had been involved in a board at Apple when he talked about the old math of computers and operating systems and the new math of a digital lifestyle. And he got the same reaction: Hey dude, like, Macs and operating systems are our entire thing. What are you talking about?

So it was hard to convince folks. But then Sidney Kimmel invested $110 million into us, and that had never happened—that was like the fifth largest gift for any medical school in the country. And then Bernie Marcus gave us $14 million to create the Marcus Institute of Integrative Health and Jack Farber helped us create the Vicki and Jack Farber Institute for Neuroscience. Folks were starting to see it be successful.

Now, some of it was brute force. When we started telehealth, I said to my department chairs, in order for any of you to get your incentives, you have to get 70 percent of your faculty trained in telehealth. They literally wanted me fired. But 16 of 17 chairs did it—and the 17th is no longer with us. He’s alive, he’s just not with Jefferson. So some of it was brute force but then people started to see that new math take hold, right? Now it’s entrenched in the system.

We’ve started something called JOLT—Jefferson Onboarding and Leadership Transformation—because we recognized we had to really change the culture from the middle. In most health systems, 20 percent of your docs get [the culture change], 15 percent will never get it, and there’s 65 percent in the middle. Well, we found that we spend 40 percent of our time with the docs that get it, 45 percent of our time with the docs that will never get it, and the least amount of time with those in the middle.

So we said we’re going to teach the teachers so we can spend less time with the people who get it— they’ll be the proselytizers—and we’re going to ignore the folks who will never get it. We call that administrative hospice—we just let them be comfortable and hope they’ll go to a competitor. And then we spend most of our time and energy on the folks in the middle. That starts to change the culture. So instead of questioning why we’re doing something different, we have this big group of people in the middle who are questioning why we’re not doing something different.

Now, where it gets difficult is as you bring in new places like Einstein. It wasn’t hard with Philadelphia University, because they’re designers and architects and were like, Oh, you think you’re cool—we’ll show you cool. But bringing in traditional health systems has been difficult so part of our work with Einstein will be how do we bring you into this entrepreneurial culture.

LP: Finally, you have an alter ego—Dr. DJ Klasko. You’ve long been an accomplished deejay. Are you still killing it as an MC?

SK: Just did it this morning. I’m deejaying a national health summit soon. And I’m working on a book about my deejay thing— everything I know about 40 years of medical leadership comes from five decades of music. So I’m taking 10 songs from every decade of my deejaying—the 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, 2000s—and going into their meanings and teasing out their lessons for leadership.

LP: Well, thank you, Dr. Klasko. I think it’s only appropriate that we go out with the MC stylings of Dr. DJ Klasko: