To Jonathan Arrieta, a lifelong resident of Kensington, the dilemma is clear: As one of the poorest areas in the country’s poorest big city, Kensington needs serious work to make it a viable area for families to live and thrive. That means shaping the North Philly neighborhood to accommodate diverse residents, bringing in jobs, cleaning and greening, helping local businesses to succeed.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

But those changes can be a mixed bag, especially if it means longtime residents—people like Arrieta’s mom, the friends he grew up with, the entrepreneurs he interacts with daily as business corridor manager for the nonprofit neighborhood group, Impact Services — can no longer afford to live there.

![]()

This, in many ways, is the story of neighborhoods all over Philly: How much new interest is good? And how much is too much? This is a dilemma socially conscious developer Shift Capital has faced — and tackled — over the last several years in Kensington, bringing in jobs, businesses and relatively affordable housing, while deliberately working to mitigate the effects of their efforts.

“We need new people with discretionary income to move into the neighborhood,” says Shift CEO Brian Murray. “On the other side of it, this is where a lot of the cultural tensions come in to play, where new and old are not talking to each other and mixing. We started to wonder: How do we solve that equation?”

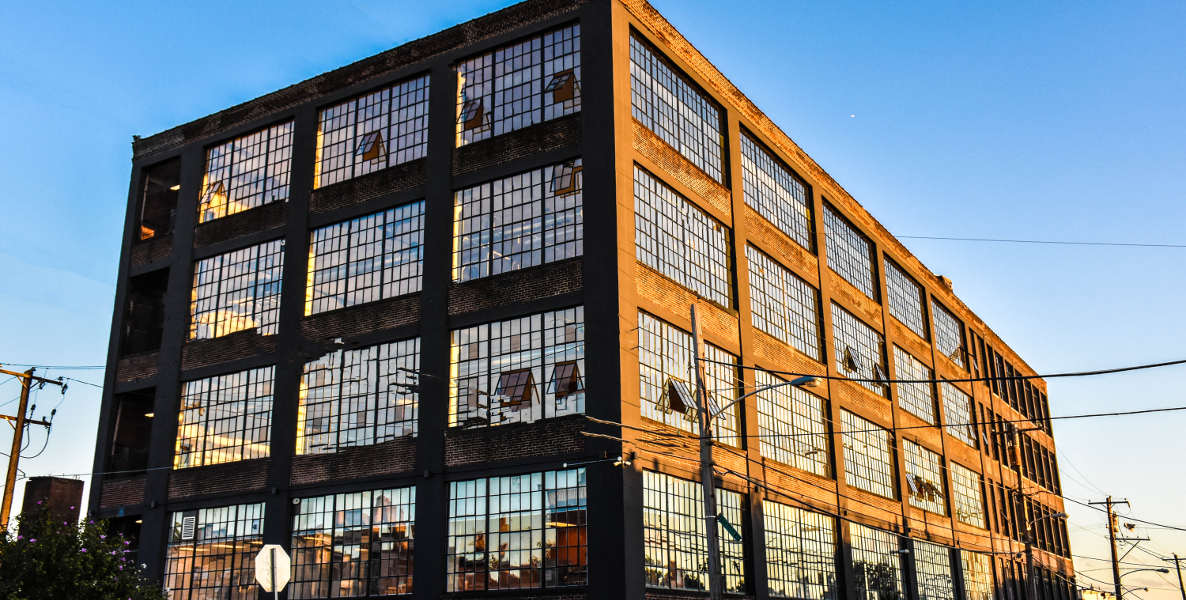

Shift’s answer is with its latest project, J-Centrel, a multi-use converted warehouse on J Street that will have 116 apartments and what Shift is calling a “Good Neighbor Program”: Residents will be encouraged to volunteer four hours a month with a community organization in exchange for up to $100 off their rent. The intention is to embed new residents with longtime neighbors, to help fix what ails Kensington and to create a community in which all are a part.

J-Centrel is the next piece in a puzzle that Shift, a certified B Corp, has been putting together since 2013 when Murray, a former PriceWaterhouseCooper accountant-turned-impact-real estate investor launched the company with a unique model — to create socially, environmentally, and culturally-conscious commercial and residential spaces that consider the needs of the neighborhood, as well as the profit margins of the business.

Last year, after buying some empty storefronts on Kensington Avenue, Shift launched the Kensington Storefront Challenge, awarding $10,000 in renovation money and up to a year’s free rent to nine small businesses to set up in the area as part of an effort to create a vibrant gateway for the neighborhood. (One of those, Vietnamese coffee shop Càphê Roasters, will now be part of J-Centrel.)

Shift has renovated and built several single-family homes near its MaKen Studios for people earning 70 percent of the area’s Adjusted Median Income (AMI). Around 95 percent of those are from the neighborhood itself. J-Centrel, which is slated to open in February, is Shift’s first foray into multi-family housing at a time when Kensington—best known these days for its role as the center of the opioid crisis — is on the cusp of becoming the next Fishtown, which itself was the next Northern Liberties. Nestled along the El, it’s ideally located for jobs in and around Center City — which means, it’s also ideal for the kind of unbridled development that haunts neighborhoods.

“We need new people with discretionary income to move into the neighborhood,” says Shift CEO Brian Murray. “On the other side of it, this is where a lot of the cultural tensions come in to play, where new and old are not talking to each other and mixing. We started to wonder: How do we solve that equation?”

On its ground floor, J-Centrel will have 30,000 square feet of commercial space, including some retail, spaces for entrepreneurs and artists, and Smith & Roller‘s Idea Factory Lab, an accelerator for local businesses. Taayib Smith’s Little Giant Creative helped coin the name — J for J Street; Centrel as a nod to the surrounding Hispanic neighborhood and to being a central hub of activity for Shift.

On the upper floors will be 116 mixed-income apartments: Two loft units will be $689/month, affordable for people at 40 percent of the AMI; 31 will be around $1,150, for people earning 70 percent of the AMI; the rest will be closer to market rate.

“We want to attract folks who are going to continue to create a mixed-income community here,” Murray says. “That’s the healthiest way to create neighborhoods, and it’s easier to bring in people with discretionary incomes to a mixed income neighborhood than a wealthier one.”

The volunteer piece serves a few purposes: J-Centrel may attract people who just think it’s a good place to live; for others, the service opportunity can provide an easy way to get more involved, without the struggle of figuring out how to do that. It gives residents a way and a reason to know their neighbors in the building, to learn about a local nonprofit, and to become integrated into the community.

Plus, there’s the value to the community itself: J-Centrel will deliver 300 to 400 hours of volunteer service per month. The hope is that many of the residents will use their service as a jumping off point to get even more engaged — join a board or a civic association, volunteer additional hours, get to know other opportunities in the area. “This is a bridge, as opposed to showing up cold turkey and trying to figure it out on your own,” Murray says.

“The question is: Who are we making this neighborhood good for?” says Arietta. “That matters more to me than just making this all good.”

Shift took inspiration in part from Oxford Mills, D3 Developers’ East Kensington apartment building which offers discounted rent to public school teachers. (D3’s new project will offer the same model for health and wellness workers.) Like Shift, D3’s principals, Greg Hill and Gabe Canuso, are doing a balancing act: They are a for-profit developer, with a mind on two missions — making money and doing right by the neighborhood.

Murray is conscious of that balancing act, and of what’s at risk. J-Centrel is an experiment. If all goes as planned, it could be a model for other developers in other parts of the city, or even the country, a way to increase civic engagement at a time when it is most needed. But it could also not work, for lack of interest, or poor execution, or unforeseen hiccups in the way residents connect — or for factors beyond its control.

Arrieta first encountered Shift through an outpost of Jumpstart Germantown, the nonprofit that helps individuals buy and develop properties, to keep investment local. He now owns a few houses in the neighborhood, including one that he bought to rent to friends, who will eventually buy it from him. His goal, he says, is for people in and from his community to own their homes, and keep them. He is grateful to Shift for leading the way — and also cautious.

“Shift Capital is the best kind of developer because they’re interested in working with the community,” says Arrieta. “And we can use all the volunteer hands we can get. But any large scale investment opens up the door for gentrification. The question is: Who are we making this neighborhood good for? That matters more to me than just making this all good.”