When politicians don’t want to make a tough call, what do they do? They outsource to a task force or commission. Last week, Jim Kenney ripped a page out of that playbook. The Kenney administration punted the ultimate decision on what to do with the Rizzo statue to the nine Philadelphians who make up the Art Commission which, by mandate of the city charter, consists of “the commissioner of public property, a painter, a sculptor, an architect, a landscape architect, a member of the Commission of Parks and Recreation, an experienced business executive, and two members of a faculty or governing body of a school of art or architecture.”

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.The Art Commission is described in the charter as a “design review board.” Now it will be making what is essentially a political judgment. Kenney was right when he mused that the debate over whatever happens with the statue will “divert attention” from real issues facing the city; whatever happens with it, it won’t affect the actual condition of any one Philadelphian. “All over a piece of metal that people love or hate or don’t care,” Kenney said. “I don’t think people are too torqued up about it.”

![]()

Kenney’s reaction to the storm created by Gym confirms the too-hot-to-handle nature of the debate. Cleverly, the mayor, rather than weigh in with an opinion, issued a call for ours. Between now and September 15, citizens can submit “Ideas For Rizzo’s Future” at the city’s website by clicking here. Presumably, the public call for ideas, combined with October hearings and a decision of the Art Commission, will insulate elected officials from political blowback, however this drama plays out.

Let’s move the Rizzo statue to stand alongside Catto—a signifier to all that our city, the birthplace of American democracy, recognizes that we’re in an ongoing conversation, messy though it is, in pursuit of that ever-elusive more perfect union.

Well, here’s one man’s modest proposal for how to get past all the shouting and ducking for cover and turn the Rizzo statue controversy into a teachable moment: Next month, the city will unveil its first-ever statue on public property honoring an African-American, the long-forgotten educator, activist and Jackie Robinson-before-there-was-a-Jackie Robinson ballplayer Octavius Catto. Let’s move the Rizzo statue to stand alongside Catto—a signifier to all that our city, the birthplace of American democracy, recognizes that we’re in an ongoing conversation, messy though it is, in pursuit of that ever-elusive more perfect union.

Don’t know Catto? You’re not alone. He’s been lost to history, though he’s made something of a comeback in recent years. I first came across him in Sam Katz’s documentary Philadelphia: The Great Experiment, in its “An Equal Chance (1855-1871)” half-hour segment:

Then there’s the book “Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto And The Battle For Equality In Civil War America,” by former Inquirer writers Dan Biddle and Murray Dubin. Catto, Biddle recently explained on NPR, “fought to integrate big league baseball 80 years before Jackie Robinson, fought to integrate the horse-drawn streetcars of Philadelphia 90 years before Rosa Parks, and marched for voting rights a hundred years before Selma.”

Catto’s Pythians, one of the first Negro league baseball clubs, played in Fairmount Park and, in 1869, made front page news by beating an all-white Philadelphia team. Unlike Robinson eight decades later, Catto didn’t turn any cheek to inequality or discrimination. He led a crusade to guarantee voting rights to all, regardless of race or “previous condition of servitude.” On a bloody election day in 1871, he was shot to death at 9th and South Streets, one of 6 black Philadelphians killed that day. He was all of 32 years old.

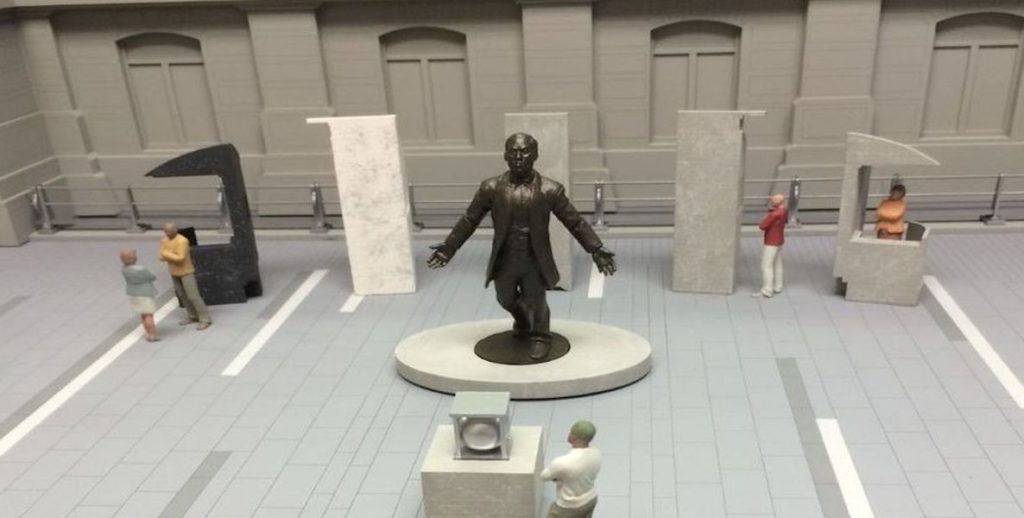

The way you answer speech that offends is with better speech—speech that, as Abraham Lincoln once said, appeals to the better angels of our nature. Pairing the Catto statue with Rizzo’s would have its challenges; Frank’s faithful might be put off, for instance, that Catto’s 12-foot stature towers over the Big Bambino by two feet. But it would enlist both men’s stories in a teachable moment for the city today; I can envision a blue-ribbon panel of historians, public intellectuals and civic leaders devising ongoing programming tied to the pairing, jumpstarting a citywide type of Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

The way you answer speech that offends is with better speech—speech that, as Abraham Lincoln once said, appeals to the better angels of our nature.

Moreover, it would give both Catto and Rizzo a chance to make one more contribution. For Catto, it offers another pass at speaking truth to power, through the ages. For Rizzo—who, during his last campaign for Mayor in 1991, had mellowed and was campaigning in black neighborhoods—it’s a chance to engage in a constructive dialogue his close aides at the end swear he was eager to have.

For us, we wouldn’t be erasing our history so much as grappling with it. Isn’t that what smart, introspective democracies ought to be doing?