If a medicine can hold a belief, the credo of naloxone is this: Addicts are human. They deserve to live.

This belief is also the founding principle of Prevention Point, a multi-service health organization centered in Kensington, and it’s lived experience for Elvis Rosado.

Rosado is Prevention Point’s outreach and education coordinator, and in the year or so since naloxone—better known by its brand name Narcan—became widely available, he’s used the drug about two dozen times. He pauses, counting the OD’s in his mind. “Maybe two dozen,” he says.

Prevention Point staff, who performed 236 overdose reversals last year alone, has taken up a street health initiative that crosses the city. In 20 minutes, they’ll teach you how to save someone’s life with Narcan. Rosado himself has trained about 2,000 people in the last 18 months.

He once revived someone on one corner while bystanders were tapping him on the shoulder, pointing across the street to another addict that had just hit the ground. “I wish I could clone myself,” Rosado says.

Rosado and Prevention Point are doing the next best thing. Prevention Point staff, who performed 236 overdose reversals last year alone, has taken up a street health initiative that crosses the city. In 20 minutes, they’ll teach you how to save someone’s life with Narcan. Rosado himself has trained about 2,000 people in the last 18 months. On any given night, he’s in a living room, training parents, husbands or wives, or in a fire hall, training paramedics.

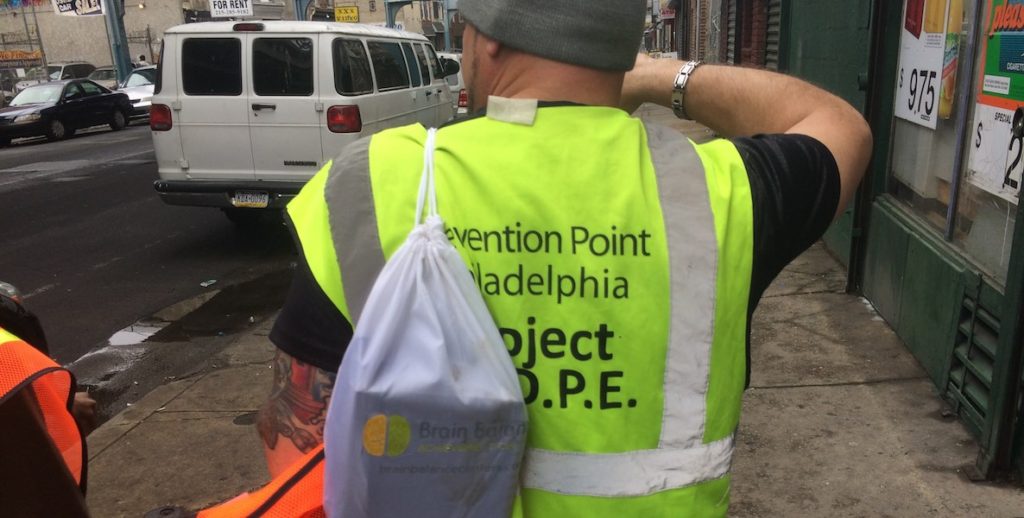

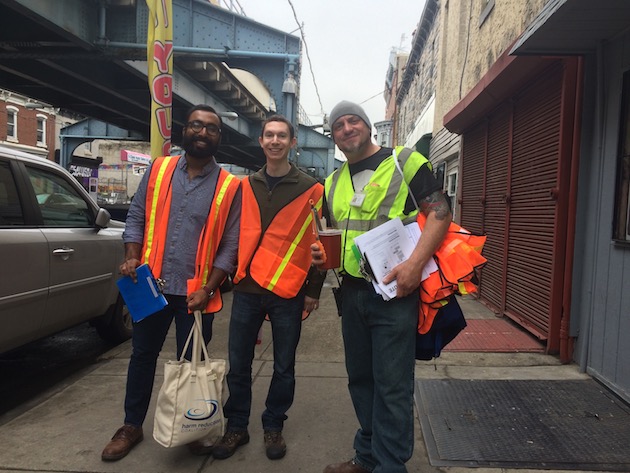

On the day I visited Rosado, he was leading a half dozen Drexel University med students in an ongoing project to train shop owners, used car dealers, bartenders—anyone— up and down Kensington Avenue how to stop death with Narcan.

Stopping death has been at the core of Prevention Point from its beginning as an underground clean needle exchange in the peak of the AIDS crisis. They got legal under a 1992 emergency order from Mayor Ed Rendell, and played a major role in reducing the intravenous HIV infection rate from 42 percent or higher to just 5.4 percent. Prevention Point has since created a sprawl of programs that treat addiction and its harms from multiple fronts. Two years ago, that sprawl condensed into a new location on Kensington Avenue. The organization now lives in a mammoth, brownstone church that rises hard against the El.

On a rainy, late-March morning, people fill the waiting room couches. They line up for the coffee urn, sign in for a health screening or a pack of clean needles. They check in with case managers, collect mail, or just get warm on the couches and watch a soap opera. Jokes are shouted over the din.

In the clinic space, Rosado’s team of Drexel med students are assembling Narcan kits across a desk and examination table. Meanwhile, Rosado is somewhere in Prevention Points’ labyrinth, collecting Spanish language instructions to enclose in the kits.

“Elvis is humble, but he’s pretty much the Narcan trainer for Eastern Pennsylvania,” says Rohit Mukherjee. Mukherjee is a medical student at Drexel University who has been working at Prevention Point for a year.

“When I grow up, I want to be Elvis,” says another med student.

Mukherjee confirms, “Life goal: Be Elvis.”

The man himself appears in the door, Spanish instructions in hand. He’s donned a yellow safety vest. It obscures the Punisher logo of his black T-shirt. Rosado is broad-shouldered. He shaves his head and wears a ring with a dragon’s skull. He’s in the class of men that can shoo drug dealers from a corner, an act I witnessed and unwittingly participated in earlier that day.

His toughness, however, plays a minor role to his warmth. He and a few of the students hug, laughing just to see each other.

The purer the heroin, the more direct the source, says the DEA and Department of Justice. By this shorthand, Philadelphia or somewhere nearby is likely the heroin entry point for the Boston to D.C. megalopolis. The authorities imagine arrival by port, where a tiny percentage of what comes in gets inspected. The supply then shoots up and down I-95, the East Coast artery. It flows from off-ramps into neighborhoods. Kensington ranks high among the markets.

You don’t need to see the handoff for evidence. Addicts fix in broad daylight. They overdose in the public library.

The librarians at the McPherson Square branch at Kensington and Indiana, a classical building on a green rise off of the avenue, have found people slumped over in the bathroom stalls.

For this reason, it’s the first stop of the day for Elvis and his team.

The Drexel students load a dozen blue pouches bearing the words Opioid Overdose Rescue Kit onto the librarians’ desk. Mukherjee quizzes the librarians on how to administer Narcan. We’re in the kids section, surrounded by the likes of Curious George and Flat Stanley. One of the librarians, a serene woman with long grey hair, smiles as she aces every question. “We’ll be all right,” she says.

We follow Rosado out between McPherson’s columns. From the marble steps he picks up a needle with a pair of tongs and drops it into a small, red medical waste bin tucked under his arm. Within a block, he has five more. You get an eye for them, distinguishing the plastic barrels from the straws and busted pens. You spot them half-submerged in a puddle of brown water at the curb cutaway.

Philadelphia or somewhere nearby is likely the heroin entry point for the Boston to D.C. megalopolis. The authorities imagine arrival by port, where a tiny percentage of what comes in gets inspected. The supply then shoots up and down I-95, the East Coast artery. It flows from off-ramps into neighborhoods. Kensington ranks high among the markets.

Born in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Elvis Rosado grew up here. He ran wild, playing handball and hopping the trains on American Street. He first got high at 11 years old. At 18, he survived a heroin OD. “What does an overdose feel like?” I ask him.

“You don’t feel anything,” he tells me. The fingers turn pale, and that paleness spreads. By the time it reaches your face, you’re down. You’ve stopped breathing.

At 21, Rosado was homeless. He shot up in abandoned buildings. He ate pills, snorted coke and sucked tubes of pure codeine syrup. When he kicked it all a few years later, he did it on the floor of a prison cell.

Rosado got a transfer to a treatment center, and after demonstrating good behavior the director offered him a day pass, Rosado’s first whiff of freedom in years. He turned it down. The treatment center was in the heart of the old neighborhood. The graveyard where he used to sleep was a few blocks away.

“I told him: My nightmare is on other side of that door,” Rosado remembers. “If you let me out, I said, I won’t make it back.”

That day happened to be his birthday, his first sober one in thirteen years.

After the library, Rosado’s team is back on the avenue underneath the El. We step from the curb into a living room devoid of daylight. Two dozen men fill couches and chairs and stand shoulder-to-shoulder along cream-colored stucco walls. Their conversations in clipped, Caribbean Spanish drop to a hush. Somewhere, there’s a gas leak.

This is not a store, and apparently I have a quizzical look on my face. “It’s a recovery house,” Rosado tells me.

My mind shoots to the Air Bridge scandal, in which addicts from Puerto Rico were shipped to phony rehabs that had sold their families a bill of goods. I can’t say that this was such a place. But certainly these men are facing tough odds.

On the other side of the door in a strange country, heroin beckons. It can creep in deadly pure and laced with fentanyl, a painkiller many orders of magnitude more potent than morphine. Worse yet, when an addict is in recovery, tolerance drops and the probability of overdosing increases. Some of these men may not make it home.

They lean in, ready for the training.

Rosado nods to Hiral Lathia, one of the students, and she takes the lead. You have to clear the mouth of food, candies, whatever. Get the person’s lungs going. Give mouth-to-mouth “rescue” breaths—one every five seconds—and then assemble the Narcan device.

This is tricky. Narcan comes in a little glass vial and the syringe barrel is only slightly larger. Take the caps off of each and screw the vial into the barrel. Someone is dying before you. Nervous fingers could easily drop the whole affair, cracking the vial on the sidewalk or a bathroom’s tile floor. Stay calm. Screw the “atomizer” on the head of the syringe barrel and spray half of the dose in one nostril, and half of the dose in the other.

Step-by-step, the training takes about half an hour. Lathia runs everything through a young man with rectangular glasses. He translates to the men. They nod at each point. They examine the Narcan vial, the syringe barrel and the atomizer as the pieces make a circuit around the couches. They give the face-shield, a prophylactic mouthpiece to protect from blood and saliva, an appreciative frown.

With his back against the door, Elvis Rosado pipes up in Spanish to underscore a few vital points:

Always call 911. No one should be afraid of the law in responding to an OD. They’re covered by El Buen Samaritano, the Good Samaritan Law.

Every pharmacy in Pennsylvania has a standing order for Narcan, and while a few mom-and-pops might not have heard, Walgreens and CVS are a good bet.

Also, when someone OD’s on fentanyl, go right to the Narcan spray. How can you tell if it’s fentanyl? From the back of the room, a lanky kid with a top-knot calls out, “There’s no nod. They just drop. The lips are blue.” And the jaws lock up, Rosado explains. You need the Narcan to relax the body.

Finally, a large dose of Narcan can knock the addict into withdrawal, waking them to shakes, nausea and muscle spasms. But the opiate outlasts the Narcan. If the addict fixes to get rid of the withdrawal, they’ll get a double dose when the Narcan wears off, possibly sending them back into OD.

The training is done. Hypothetical Narcan administered with heavy sighs. The men lean back into their couches and chairs, nodding and conversing once more.

Rosado ducks out and joins Mukherjee and another student who are wrapping up a training a few storefronts down. Mukherjee passes out fliers for Vigilantidote. Vigilantidote is a new SMS texting group for Philadelphians carrying naloxone. It aims to build network of trained overdose responders to support the city’s emergency services.

“You could save someone’s life!” exclaims an employee behind the counter. “That’s somebody’s son or daughter. Or mother!” she says.

“Definitely,” the owner says, reading the sheet. He’s a contractor and for reasons that will be immediately obvious, has asked that I keep his business out of the story. He spots Rosado and a smile hitches up one side of his face. “Didn’t you work at Kensington hospital?” the contractor says.

After Rosado got sober and free, he volunteered at Prevention Point, got a bachelors, went to grad school and worked across the city in education and recovery. “Yeah, I had an office there for a while,” Rosado says.

“I think I kicked in your door!” the contractor says.

“Was it you that stole my CD player?” Rosado says.

“I don’t know. We were looking for pills. Used to eat whatever from the closets and go off walking into walls,” the owner says.

“All those CDs,” Rosado says, shaking his head. The students and I are wide-eyed. But this kind of serendipity is not strange for Rosado. “Man,” he laughs, “those CDs!”

Rosado got a transfer to a treatment center, and after demonstrating good behavior the director offered him a day pass. He turned it down. “I told him: my nightmare is on other side of that door,” Rosado remembers. “If you let me out, I said, I won’t make it back.” That day happened to be his birthday, his first sober one in thirteen years.

The contractor leans against the wall. “I got sober in 2011,” he says. He and Rosado don’t know each other, not really, but the contractor can spot a fellow traveler. After a beat, he chucks his chin at Rosado and asks, “You?”

“I’m 25 years. Last February,” Rosado says.

“I never thought I’d get off these streets,” says the contractor. “I thought I die out there.”

Rosado nods and rocks on his feet. “A lot of us did.”

We leave. Most of the students have class. I head for the El, walking with Rosado a little more. There’s a t-shirt shop up the way that expressed interest. Rosado stoops to pick a syringe from the seam of a sidewalk.

“I know that’s right,” says a woman. She’s catching a smoke outside the red door of a bar that offers fine food and cold beer. “Them fucking needles is everywhere. God bless you.”

Rosado clicks the tongs in the manner of a cartoon crab and moves on. We pass a toddler struggling to free himself from a stroller. You can imagine a needle piercing the canvas lip of his shoe.

At the Somerset El stop, Rosado and I part ways. Up on the platform, it occurs to me that the needles along Kensington Avenue likely come from Prevention Point. They’ve kept thousands alive. Better to have needles in the gutter than human bodies.

Just before train arrives, I spot Rosado across the street. He’s walking, scanning the sidewalk, cleaning up.