Ahead of the next presidential election—and in the wake of Russian interference in the last—a bunch of good-guy hackers assembled in Las Vegas last summer to test the defenses of America’s ballot-counting infrastructure. It didn’t go over well. Twenty-nine machines currently in use across the United States were selected from portfolios of the nation’s largest voting-machine manufacturers. According to press reports, the hackers, including an 11-year-old, made quick work of infiltrating voter databases and adding viruses to alter voting outcomes.

One voting-machine maker received special rebuke, Nebraska-based behemoth Election Systems and Software (ES&S), not only because of perceived flaws in its technology, but also the corporate messaging it put out in the immediate aftermath of an autopsy report written after the convention, DEF CON 26. “Hacking just one of these [ES&S] machines could enable an attacker to flip the Electoral College and determine the outcome of a presidential election,” concluded six cybersecurity experts in attendance, a group that included Professor Matt Blaze of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Here we are, the largest county in the state of Pennsylvania, which is sure to be a battleground state, and we’re not doing the voting machine selection correctly? In a way that is best practice? It almost boggles the mind,” Rhynhart says.

It was the first in a series of public relations hurdles for ES&S, which is the largest vendor in the United States. Shortly after DEF CON, Republican and Democratic members of the Senate Intelligence Committee publicly questioned why the company had continued to sell machines with “known vulnerabilities.” Articles in the New Yorker and other outlets exposed ES&S lobbying efforts to wine-and-dine election officials across the country. In August, ES&S CEO Tom Burt penned a letter pushing back against the white-hat hackers’ findings. Later, ES&S vowed to beef up its internal cybersecurity controls.

Now that ES&S is finalizing a lucrative contract to replace Philadelphia’s existing voting machines with sleek touchscreen consoles—technology that is different from what was picked apart in Las Vegas, although also less tested—the company is making a media relations push to get voters on board with the model coming to Philly: the ExpressVote XL

“The ExpressVote XL has been used in several successful elections, including Port Chester, NY, and in Warren County, NJ, where a post-election audit proved the 100 percent accuracy of the system,” writes Katina Granger, public relations manager for ES&S. “The State of Delaware has also chosen the ExpressVote XL for use in elections statewide. This machine is EAC [Election Assistance Commission] certified, and has gone through countless hours of testing to ensure that it is safe, accurate and reliable for Philadelphia voters.” Granger cited laboratory testing performed in accordance with federal regulators, along with “independent third-party reviews, including penetration testing and source code reviews.”

Earlier this week, ES&S delivered 83 of these next-generation machines to the City Commissioners office at Delaware and Spring Garden, where a company rep has since held private demonstrations for members of the press. According to City Commissioner Lisa Deeley, there will be 3,800 of those machines at polling places come November.

But everything about the machines—from whether they are safe, to how much they cost, to how the city selected them—is still a question mark. That is largely the fault of the City Commissioners, who have been less than transparent about every part of the selection process. With so much at stake—namely, the 2020 Presidential election—the controversy stands to undermine the integrity of Philadelphia’s vote for years to come.

There could be a ballot initiative on those sleek, new touchscreens asking Philadelphians to approve the borrowing of money that would be required to purchase them. We’d be voting to fund the machines on the very machines themselves.

“Here we are, the largest county in the state of Pennsylvania, which is sure to be a battleground state, and we’re not doing the voting machine selection correctly? In a way that is best practice? It almost boggles the mind,” City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart says.

It was on February 20th when the Philadelphia Board of Elections (a body comprised of the three elected city commissioners) officially selected the ExpressVote XL, a model made by ES&S. That was the culmination of a fast-tracked request for proposal (RFP) issued by the City of Philadelphia, following Governor Tom Wolf’s statewide directive to replace aging voting machines by the 2020 elections with secure, auditable systems.

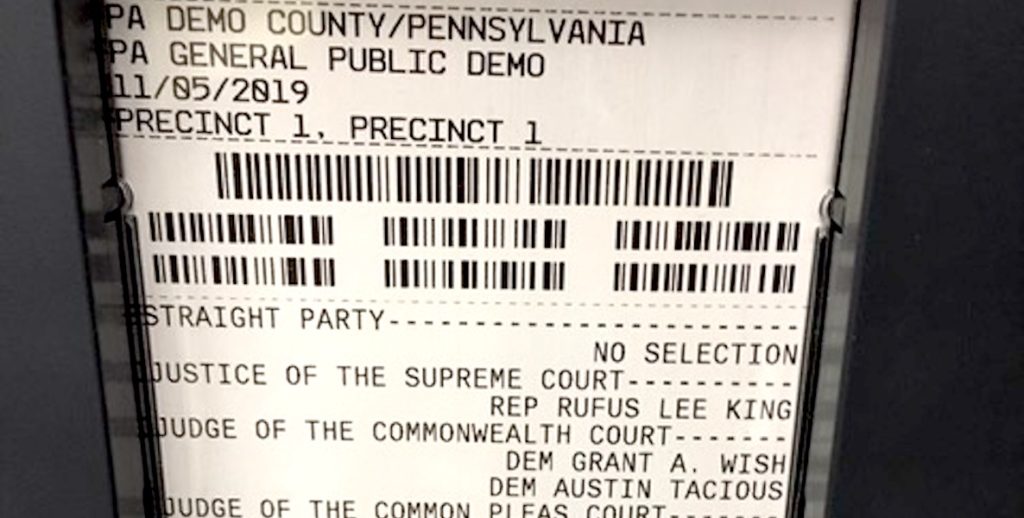

The ExpressVote XL machines appear to fit the bill. Here’s how it works in brief: Voters make their selections on a 32-inch digital touchscreen. Those selections are then printed on a piece of paper that reappears in front of voters behind a separate glass panel. Atop that receipt is a digital barcode and a summary of the selections. After the voter reviews once more, the machine sucks up the ballot and tallies the votes via barcode.

But the ES&S machines the city wants to purchase—dozens of which are already stored on public property—are the scourge of many cybersecurity experts. Since 2016, among voting integrity experts, there’s been an emerging national consensus that hand-marked paper ballots are less prone to hacking. They’re also cheaper. Philadelphia’s choice of the ExpressVote XL has raised eyebrows from both security and fiscal watchdogs, because it’s one of the most expensive models on the market ($8,000 per machine, by most estimates).

“The state’s own blue-ribbon commission recommends against barcode devices,” says Rhynhart. “Every expert says the hand-marked ballot is the most secure—secure from hacking, especially hacking from foreign countries—and they’re cheaper.”

Defenders of the ExpressVote XL say those security concerns are overblown, and they’re moving as fast as needed to satisfy Governor Wolf’s aggressive mandate. “The recent presentation and all of the previous and ongoing processes are part of a coordinated effort by several city departments to ensure that Philadelphia can smoothly transition to the new voting system on an abbreviated timeline as required by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” writes deputy city commissioner Nick Custodio.

Some groups representing voters with disabilities have come out in support of the ExpressVote XL. Powerful democrats in the city have also stood behind the machine. If we all figured out how to buy a hoagie at the digital kiosk at Wawa, the thinking goes, can’t we get used to this?

Maybe, but only if the process to buy these machines didn’t stink so bad.

“It would appear the Request for Proposals was written to favor one vendor,” Pennsylvania Auditor General Eugene DePasquale told reporters in early February.

“I want you to know that Commissioner Clark’s office was not aware—we did not receive an email—that these machines would be here yesterday,” said Commissioner Anthony Clark at the weekly Board of Elections meeting on May 1. “How the machines came, I don’t know. Who’s paying for them, I don’t know.”

Yes, the same Anthony Clark—speaking in the third person—who has a notorious reputation in local government for his inability to show up to work, is now the only member of the Board of Elections that’s vocalized concerns about the legitimacy of the process leading to the ES&S contract. Clark has come out in support of Rhynhart’s request to vacate the previous decision.

It’s also important to note that Clark is the only commissioner currently on the board. Within two days of the February 20 vote, both his fellow commissioners, Al Schmidt and Lisa Deeley, had recused themselves from further City Commissioners Office deliberations. Pennsylvania election laws forbid sitting commissioners from presiding over that office while running for reelection. Both Schmidt and Deeley filed their nomination paperwork the week of the vote to award the ES&S contract, and were replaced with two judges in the interim.

Prior to their recusals, Schmidt and Deeley oversaw a procurement process that involved the use of a confidential committee whose members—still unknown to the public, despite a subpoena issued by the city controller to get the information—were made to sign confidentiality agreements.

Clark refused to sign any such agreement. On Wednesday, it came to light that Clark’s refusal to sign it was the reason the Commissioner’s Office kept him in the dark about the advanced delivery of 83 machines. “There’s a reason why you didn’t know,” Custodio said, to Clark in an exchange at City Hall. “The press didn’t sign a confidentiality agreement, so why would you tell them?” Clark responded.

Clark was referring to an NBC10 interview that aired Tuesday with the recused Commissioner Deeley showing off the new machines, a segment which got several mentions at Wednesday’s Board of Elections meeting, with one advocate calling it “a campaign ad coming out of the Commissioner’s Office.”

Sources close to the City Commissioners say that the machines are here because the office, in the throngs of preparing for this month’s primary elections, will need as much time as it can get to train poll workers on the new system in time for November. The office also plans to hold public demonstrations of the ExpressVote XL throughout the city starting this summer.

But there are ethics questions being raised about how a company on spec can ship dozens of machines, valued at more than a half-million dollars, to the offices of public officials. And it adds to critics’ suspicions that elected officials had ES&S in mind well before the RFP was issued.

“It would appear the Request for Proposals was written to favor one vendor,” Pennsylvania Auditor General Eugene DePasquale told reporters in early February. Pasquale openly raised questions about undue influence. “Did anyone meet with a lobbyist? Did anyone get taken to dinner? Did anyone receive a donation or trip?”

(It’s not a totally crazy thought: In the 1970s, a United States Tax Court found former City Commissioner Thomas McHenry received kickbacks from a voting-machine maker worth more than $100,000.)

The fact that DePasquale can even ask those questions about a public RFP is a testament to how uniquely opaque this procurement has been, and is one reason Rhynhart says she will not authorize payment of the machines.

“The delivery of these 83 machines before a contract has been signed or funding approved by City Council shows just how broken this process has been, every step of the way,” said City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart in a statement. “I’m deeply concerned about the legality of this process, and as City Controller, I will not release $1 of payment while these questions go unanswered.”

For generations, the City of Philadelphia procured services and materials by awarding contracts based on the criteria of “lowest responsible bidder.” But in November 2016, a majority of Philadelphians voted in favor of changing that process, approving a ballot measure that replaced lowest bidder with “best value”—a standard that’s been adopted in most major American cities.

At the time, opponents warned that best value was ripe for cronyism, while a louder group of proponents backed it as a means to opening up city contracts to smaller vendors, including women- and minority-owned firms. It was widely assumed that best value would accelerate diversity and inclusion goals contained in Mayor Jim Kenney’s massive Rebuild initiative.

The new procurement’ systems biggest champion was Deeley’s former boss, Councilman Bobby Henon, who is seeking reelection amid a federal indictment on corruption charges. “As far as the last and loudest criticism about best value, that it opens the door to cronyism and pay-to-play politics, I can say the following: this process will be transparent and open at every turn,” Henon said during a December 2016 council meeting. “Despite the claims of some, and I am proud to say this, best value is good policy.”

The procurement process involved the use of a confidential committee whose members—still unknown to the public, despite a subpoena issued by the City Controller to get the information—were made to sign confidentiality agreements.

The first major test of best value has been the voting machine RFP, and to many people, it’s been a red flag. “I supported best value back in 2016 because it’s a best practice when used correctly,” says Rhynhart. “But part of using it correctly is transparency. The public needs to have clear information on how vendors are being measured, how vendors are being selected, so that the public has confidence the best value has really been used to pick the best vendor. And that clearly hasn’t happened here.”

Rhynhart has also raised questions about whether or not the City even has the money to purchase the flashy new modules. In Mayor Kenney’s latest budget plan, there’s $22 million of proposed capital funding for new voting machines—a proposal that still needs Council approval. There’s an additional patchwork of state and federal subsidies that could knock down the costs by a few million dollars.

Except the overall cost of the new voting system, according to previous statements from the city commissioners, could be in the neighborhood of $60 million. Plus, councilmanic approval of Kenney’s capital budget is only one step in the process. Voters would then be asked to approve public bonds to borrow the money for that capital expenditure. The soonest it could hit the ballot would be November—the deadline for new voting machines.

In other words, there could be a ballot initiative on those sleek, new touchscreens asking Philadelphians to approve the borrowing of money that would be required to purchase them. We’d be voting to fund the machines on the very machines themselves.

Huh.

There’s also a separate question about the legality of the February 20 vote at the Board of Elections. Deeley had already scheduled a campaign fundraiser for the night of February 20 and had been advertising it for weeks beforehand. Is that not a declaration of candidacy, Protect Our Vote Coalition members openly ask? And, if they couldn’t begin campaigning until after the voting-machine decision, then could the entire process have been expedited to benefit their campaigns?

“The February 20 vote was and is invalid,” Emmie DiCicco, a member of the Protect Our Vote Coalition, said at a March meeting of the City Commissioners. “The commissioners had a major, direct conflict of interest.”

Off-the-cuff remarks made by Democratic brass have since indicated many people in city government remain satisfied with the selection of ES&S. Those theories haven’t been quelled, in part because of comments like the ones made by Representative Bob Brady at Deeley’s February 20th fundraiser.

“Any problem I ever had, for I dunno, 15, 20 years, I called you and you solved it,” says Brady, in a video captured at the event. “But now you’re a Commissioner. You’re doing the same thing. You’re not only doing the good stuff today like you did to get the right voting machines—forget them other kind that, uh … maybe I shouldn’t be mentioning it but I don’t care.”

Now there are dwindling options for intervention. Without Schmidt and Deeley—who were replaced by Judge Vincent Furlong and Judge Giovanni Campbell—there’s been no indication of reissuing an RFP or selecting a new vendor, outside of Clark’s last-ditch pleas. So far, five challengers have come out in favor of Rhynhart, signing a letter that asks for the original vote to be invalidated and for the process to be restarted.

“There’s been this really rushed process and then the funding is not there until December to sign a contract, so there’s plenty of time to go through a real process,” says Rhynhart. “There is still time to right this if those in decision-making powers—Judge Furlong or Judge Campbell—if they want to right it.”