I was recently at one of my favorite parks, the Anna C. Verna playground at FDR Park, where it’s usually so crowded, my kids have to wait to use the swings and get in line to go down the slides. But on a steamy end of July weekend, most of the swings sat empty. It’s not because the families that use this park are at the Jersey Shore: It’s because there was no shade.

Trees that might otherwise have provided some relief were dead and leafless. Kids and parents grouped in the few spots where they could secure shade — a climbing structure for the kids, a small pavilion with three picnic tables for adults. While we have frequently spent half a day at this park in the cool gray of fall, this sunny, humid time we barely eked out an hour.

Much of the discussion about climate adaptation focuses on major threats like hurricanes, wildfires, and flooding. Those are important concerns. But there is the more basic fact that we’ll probably be breaking records for hottest summer every year from here on out and we’re simply not updating our cities to address this concern.

Once you start looking for the bleak, shadeless parts of cities you start seeing them everywhere — and can imagine their potential if they were turned into shady, comfortable spots.

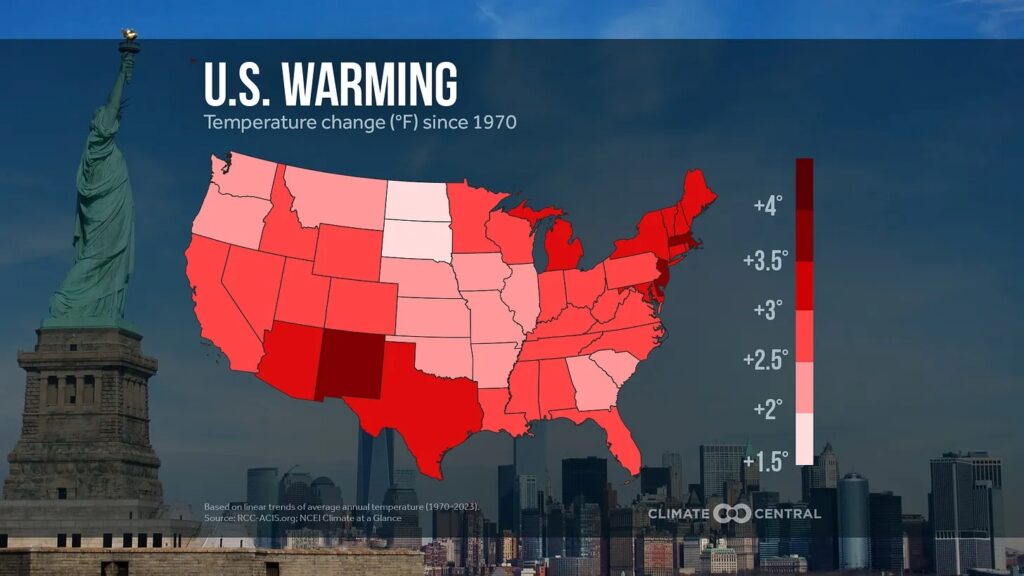

In the Northeast, many people wrongly assume that we’ll be better off in the coming decades than places in the South. But on the contrary, many states in the Northeast are the fastest warming.

As the New York Times reported, New Jersey is the fastest-warming state:

The Northeast has the fastest warming cluster of states in the country, the data from Climate Central shows. In addition to New Jersey, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine all made the top-10 list (New York comes in at No. 11). They all have experienced temperature increases of over 3 degrees, and are warming faster than sizzling spots like Arizona and Texas.

Philadelphia now has an average of 30 days per year when the temperatures exceed 90 degrees — a 50 percent increase over the amount in 1970.

Other cities’ cooling solutions

Cities that have to deal with more days of extreme heat, such as Miami and Phoenix, have stepped up to this challenge, and both have Chief Heat Officers and entire city departments dedicated to heat management. San Antonio and Los Angeles are applying cool pavement to bring down the temperature of asphalt.

Because these places have sun and warm temperatures year-round, they have designed shade into their public spaces. St. Petersburg’s pier has a beautifully designed shade screen that cools off its marketplace. Phoenix has installed shade structures at more than 3,000 intersections.

But in much of the rest of the country, where only summer brings extreme heat, there seems to be a lack of concern or wherewithal to combat hot weather in public places. It was interesting to note that one of the reasons why police officers in Butler, PA were unprepared at the July rally where Trump was nearly assassinated is that officers were busy that day, responding to more than 100 heat-related emergencies. In the Northeast, it often seems we have rudimentary preparedness and solutions for extreme heat.

Shade offers a remarkable respite in brutal heat, and yet most cities have not taken up the cause of shade. A recent article in The Atlantic discussed shade with UCLA urban heat expert, V. Kelly Turner:

With a group of colleagues, Turner surveyed 175 municipal plans produced by the 50 most populous cities in the United States to see how they are planning for heat. The team found that few cities are trying to systematically increase shade, and of those that are, 75 percent mentioned trees and just 10 percent mentioned shade structures in their plans. Trees, Turner pointed out, have a “mature institutional infrastructure” that has been speaking for them, Loraxlike, for many decades, in part because greenery beautifies cities, improves real-estate values, controls erosion, and boosts biodiversity. Shade structures don’t really have any organized lobbying groups.

Turner is right that shade needs advocacy, and that trees aren’t the only solution.

Taking up the cause of shademaking

When I was at the playground and struggling to cope with the heat, I began to mentally redesign the park, turning the big open space in the middle of the swings into a temporary, beautifully designed shade sail structure where parents could sit or kids could cool off. This thought exercise reminded me of the temporary tactical urbanism efforts that have been so popular over the years, like piloting temporary bike lanes, creating outdoor seating out of parking spaces, and adding pop-up playgrounds to lifeless plazas.

Why not advance a shademaking movement that helps create temporary shade in public spaces, at local businesses, and throughout our neighborhoods?

“Greenery beautifies cities, improves real-estate values, controls erosion, and boosts biodiversity. Shade structures don’t really have any organized lobbying groups.” — V. Kelly Turner in The Atlantic

Shademaking has the potential for transformative before-and-afters that has helped the placemaking movement succeed and grow so popular. The transformation of boring abandoned plazas or car-centric streets into lively public spaces is the engine behind placemaking; similarly once you start looking for the bleak, shadeless parts of cities you start seeing them everywhere — and can imagine their potential if they were turned into shady, comfortable spots.

Much like pedestrianizing streets, shading oppressively hot commercial corridors with shade sails or public art that screens out the sun could turn these streets into shopping magnets.

One bonus: Simple temperature checks will provide the data on how many degrees cooler it is in the shade than in the sun, making it easy for these projects to show their value and performance.

Providing shade may not be just about enjoying public spaces, but ensuring our cities are safe and functioning. Shade interventions might pay for themselves by preventing heat-related emergencies, keeping our residents healthy and saving our first responders’ time and attention for something that could be more serious.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.