It was a Saturday in March of 2014 when Sylvester Mobley’s internal Marine kicked in. His free class offering tech education to inner city kids at the Marian Anderson Rec Center in the Graduate Hospital area was about to get underway…and only one student had shown up.

It was one of those moments everyone with a new, disruptive idea faces: Do I continue? Do I listen to that inner voice of doubt?

As if he heard that voice, the Rec Center coordinator stopped in. It wasn’t the first time that turnout was so sparse. “Are you going to keep doing this?” he asked Mobley. “You only got one kid.”

Today, 20 months later, Mobley’s Coded By Kids program is popular and growing. But back then, things looked bleak. “You have to remember, I’m a Marine,” says the 36-year-old married father of three. “If you’re a Marine, you’re committed whether it’s one kid or 100. If you’re a Marine, and you see a need, you see that something needs to be done? You do it, and you apologize later if you need to.”

No apologies were necessary. Thanks solely to word of mouth, kids soon started showing up for Mobley’s project-based tutorials, where students as young as five and six years old would learn advanced coding, developing and designing websites many high school computer science teachers would find challenging. By the following fall, Mobley had added a second class of 20 kids and was teaching more than 50 other kids per week at area schools, including troubled Martin Luther King High School. He has since added Coded by U, pay-what-you-can classes for low-income adults, and will soon debut paid adult classes. He’s struck deals with a handful of schools for a program that purposefully doesn’t feel like school; Mobley’s curriculum is all about learning by doing.

“We’ve got 10-year-old kids doing the same things adult software engineers are doing at work,” he says, pointing out that some of those software engineers, from companies like Comcast, make up his volunteer staff.

Thanks to a $20,000 grant from StartUp PHL and a deal with OIC, the region’s oldest and largest provider of job training and career development services, Mobley can now dedicate himself full-time to his dream: Providing opportunity to kids who are just like he once was—eager and talented enough to learn, but oblivious of what it takes to break into the tech space. Which is why the deal with OIC can be game-changing, for Mobley and the city. Founded by the legendary Rev. Leon Sullivan fifty years ago, OIC trains many workers in the hospitality and culinary arts fields. In addition to hotel room maids and line cooks, those industries need coders and developers, too.

“In Iraq, you’re constantly asking yourself, ‘How will I be remembered and thought of?’” Mobley says. “I came back wanting to do something for my community, other than building prisons. I realized I wanted my life to be about more.”

“There is so much opportunity out there,” Mobley says. “You can have a high school degree and still get a great job as a developer. All you need is the coding skills and a laptop.”

But Mobley knows firsthand how lacking basic computer science courses are. “You basically learn how to open documents and do word processing,” he says. Talks with the ever-glacial School District to possibly inculcate his curriculum have been frustrating, to the point that Mobley has given up on them and is instead focused on expanding to other Rec Centers.

Mobley came by his passion for tech quite by accident. After four years in the Marines out of high school, the Germantown native took advantage of the Military Prior Service program, which enabled him to reenlist in a different branch without having to redo basic training. As a Marine, he was tired of the grueling physical pace. “I was cold, wet, and hungry all the time,” he says. In the Air Force Reserves, he found people working at computer stations—inside. “It looked like they were eating everyday and staying dry, so I was like, ‘I want to do that job.’”

A whole new world opened. Suddenly, Mobley was privy to passionate debates about whether Linux was better than Windows; he learned about hardware, software, and fiber optics. After four years, Mobley, full of military wanderlust, switched it up again and joined the Army National Guard. In his civilian life, he project managed the building of prisons for a construction management firm. He’d travel the country, frequently depressed by his firsthand view of just how much money we’re spending on imprisoning primarily young black men.

Once he was deployed to Iraq, he decided to make a change.

Mobley has struck a deal with OIC, which provides job training for many in the hotel and culinary arts fields. In addition to hotel room maids and line cooks, those industries need coders and developers, too.

“We all know that, at some point, we’re going to die,” Mobley says. “We don’t think about it. But in Iraq, in that environment, you think about it all day, every day. You’re surrounded by people, but you’re also extremely isolated. You spend your time looking inward, analyzing your life. You’re constantly asking yourself, ‘How will I be remembered and thought of?’ I came back wanting to do something for my community, other than building prisons. I realized I wanted my life to be about more.”

What if he turned kids onto tech, kids who were just like he’d been at their age? After all, he was struck time and again by just how few people of color worked in tech. Could that be the epitaph he was looking for? Mobley had project management chops. Why not use those skills to teach inner-city kids—instead of building prisons to house them?

So he did it. At first, it was just him and a kid or two in that Rec Center computer lab. And then word got out. This wasn’t school—it was fun! And then, with no promise of a revenue stream on the horizon, he gave up his job as project manager for Penn Medicine’s data infrastructure projects. He’d identified a need in a city with the worst digital divide in the nation.

“Once I realized this is a program that needs to expand throughout the city,” he says, “it was a no-brainer. Someone had to dedicate himself to this.”

Talk to Mobley now that his vision is starting to take shape, and the plans come, one after another. How he wants to turn Rec Centers into corridors of innovation for communities. How they should be neighborhood incubators, offering tech entrepreneurship classes for young and old alike. How already he’s seen the lives of kids turned around when this world is opened to them, as it was to him in the Air Force Reserves.

But it’s easy to outline the big plans now, now that stuff is happening. But in March of 2014? That’s when it took some vision and heart and stubbornness to plan at all, when all of one kid sat before a computer screen in that Rec Center. That’s when the old Marine saying—“No short cuts. No retreat. No surrender.”—rattled around his brain, and Sylvester Mobley did what Marines do. He took the hill that was before him. “It needed to be done,” he shrugs.

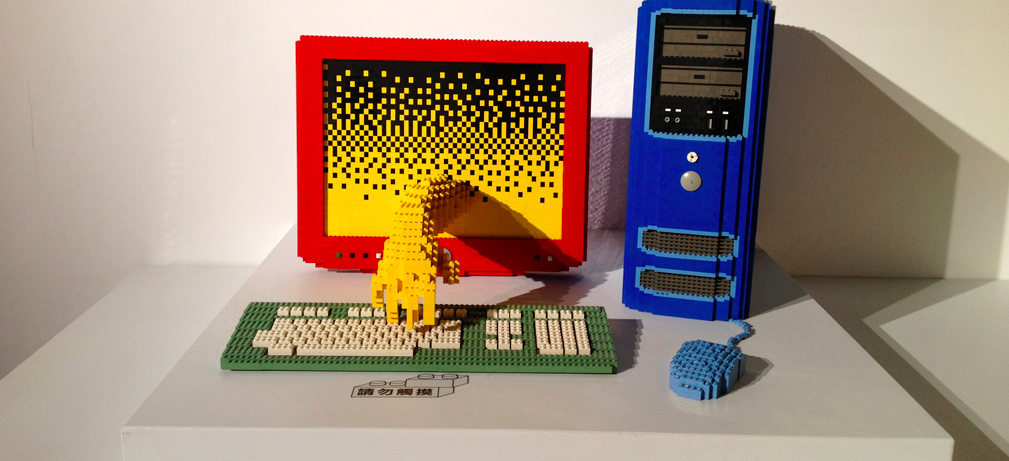

Header image of Art of the Brick via https://www.shaozhionthenet.com/.