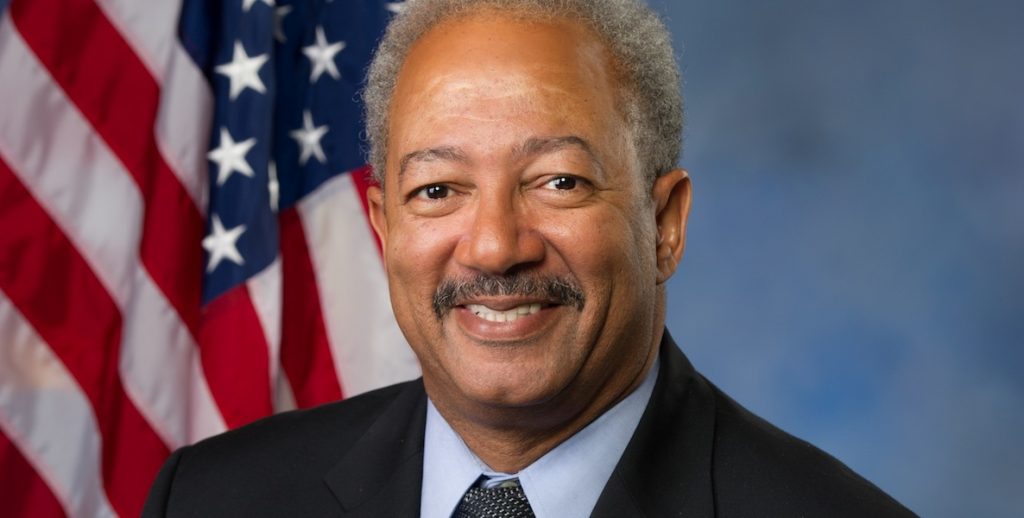

The Chaka Fattah guilty verdict earlier this week was anti-climatic. The Feds do not bring corruption charges against a sitting Congressman without a strong case. Moreover, two associates of the Congressman pled guilty and testified against him.

For all of his cool courtroom behavior, Fattah was not likely to come through this unscathed. He never had the resources to lawyer up and his defense that a few associates went rogue strained credulity.

Three associates were convicted along with the Congressman, including long time progressive activist Bob Brand. They will be sentenced in early October, along with the Congressman. Fattah will go to jail.

What a year for Fattah! He watched his son go to prison on charges of defrauding banks and the school district. His wife, a former NBC10 newscaster, lost her job; prosecutors, describing in court filings the bribery scheme involving her husband, a Porsche and supporter Herb Vederman, who was also convicted this week, suggested she’d exposed herself to criminal liability, though no charges against her were filed. Finally Fattah lost his congressional seat to State Representative Dwight Evans, after more than two decades in Congress.

Fattah was a powerful voice for Philadelphia in Congress. He had seniority on the appropriations committee. A decade ago some thought he would eventually chair the committee. He moved money to favored causes, from scholarships for inner city students to neuroscience research, something he always championed. And he had deep connections with his constituents who sent him back to Congress eleven times.

Rather than trying to pay back the $1 million loan the old fashioned political donor way—after all, Fattah was still a sitting Congressman on the appropriations committee!—the Congressman used appropriations and nonprofit grants to illegally repay it through a web of contracts and consulting relationships.

Fattah’s replacement, Dwight Evans is a smart politician but will be a first term guy without much clout. He will work as hard as anyone but it will take time to figure out D.C. after spending so many years in Harrisburg. This is the bigger stage he has always looked to capture and now he will have an opportunity to show his stuff.

Evans ran against Fattah without talking about the Congressman’s corruption charges. He let the press bring up the charges. That strategy worked. Evans got elected and received no blowback from Fattah loyalists who would have resented Evans using the indictment as a campaign cudgel.

The downfall of Fattah is linked principally to his 2007 mayoral campaign. He was unable to raise money given the restrictions that the city had just placed on political donations. In a different era he would have used Congressional relationships (like every other Congressman in America) to raise large checks from the usual suspects: law firms, money managers, real estate developers, and others.

But in the new environment he had to raise smaller amounts from a broader number of donors—something Michael Nutter did—or he had to self-fund, like Tom Knox. He was unable to do either.

To build a bigger donor base required a more energetic campaigner. He could not create citywide excitement or organize a prime time campaign team. Borrowing money to stay competitive paid the bills for his campaign operation in an election that many thought he would win.

When he lost, he had a new problem: How to pay the money back. And rather than trying to raise it the old fashioned political donor way—after all, he was still a sitting Congressman on the appropriations committee!—he used appropriations and nonprofit grants to illegally repay the loan through a web of contracts and consulting relationships.

One of the characters who had a central role in the whole affair seemed to disappear during the trial and news coverage: former Sallie Mae CEO Albert Lord.

Who is Albert Lord? He is the guy who made the $1 million loan to a Fattah consultant and associate who then funneled $600,000 into the Fattah campaign without the campaign properly reporting the source and use of the funds. Lord had previously donated $100,000 to a Fattah exploratory committee prior to the Congressman’s declaring his candidacy.

While Lord’s donations and loans were not from Sallie Mae but from Lord himself, the corporate foundation was a frequent donor to one of the nonprofits that Fattah controlled. This should come as no surprise to anyone who knows about the donations of America’s Government Sponsored Enterprises like Sallie Mae, Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac prior to the 2008 recession.

GSE’s like Sallie Mae often contributed to the favored causes of Congressional leaders who held sway over their federal subsidies and who could grant them favorable access to credit markets. And while Sallie Mae was privatized under Lord’s leadership in 2004, it still made significant money from federal loan servicing contracts and it continued to have an interest in how Congress set rules for student lending. Like other financial institutions it has a powerful PAC that donates generously to the appropriate rule writers. That is how the game works—and it is all legal.

If the story ended there it would be just another Washington D.C. influence peddling incident. But the story becomes more interesting when Lord calls in the loan and we find out how the loan gets repaid.

Sallie Mae CEO Lord, an extremely well paid executive whose compensation in base salary and stock options between 1999 and 2004 was once reported at more than $200 million, suddenly seemed to have a money problem. The indictment, where Lord is referred to as person D, notes that he was in a state of acute financial difficulty.

Lord, an extremely well paid executive whose compensation in base salary and stock options between 1999 and 2004 was once reported at more than $200 million, seemed to suddenly have a money problem. Or at least it was reported that way in some of the press coverage.

I do not know anything about Lord’s personal financial position during that period, although a lot of financial companies took significant hits in 2007 and 2008. The indictment, where Lord is referred to as person D, notes that he was in a state of acute financial difficulty. In one widely reported call with analysts in 2007 Lord lost his temper and that day the company’s value plunged by $3 billion – not solely due to Lord’s expletives, though they certainly did not help investor confidence.

When the loan gets called and Fattah repays it, the repayment came from grants that were not used for their intended purpose: $100,000 from NASA and $500,000 from Sallie Mae’s corporate foundation.

So: Al Lord makes an illegal campaign loan and the bulk of the loan is repaid by a grant that came from the charitable arm of the company he ran. Something does not pass the smell test. Did Lord’s cooperation with the Feds buy him good will? Lord testified under a grant of immunity from the Feds, and we do not know more about the nature of that negotiated immunity.

Of course, there is a history of Sallie Mae supporting Fattah’s annual higher education conference (which is what the $500,000 was to be used for) and Lord could point to that history and say this grant was no different than others and he could not know the funds would be misspent.

None of these questions about Lord are meant to detract from Fattah’s (and his associates) wrongdoing. They will now be punished and deservedly so. It does however point to the moral corruption that takes place at a different country club than Fattah and his associates attended. At that country club, money pays the bills of many politicians supposedly working on our behalf.

Al Lord was famous in the D.C. area for building a private golf course on 335 acres of prime Virginia real estate. His own country club. He flew Fattah and his wife down to Florida on his jet for the Eagles-Patriots Super Bowl. And, oh yeah, he oversaw the expansion of massive levels of student debt, with unsustainable default rates, and figured out how to make lots of money from that business. He is happily retired, apparently without anymore of that acute financial difficulty. Fattah’s retirement does not look nearly as bright.