![]()

It is one of the great pleasures of being an American, punctuated by the unsticky sticker I slap on my shirt as I walk out the door.

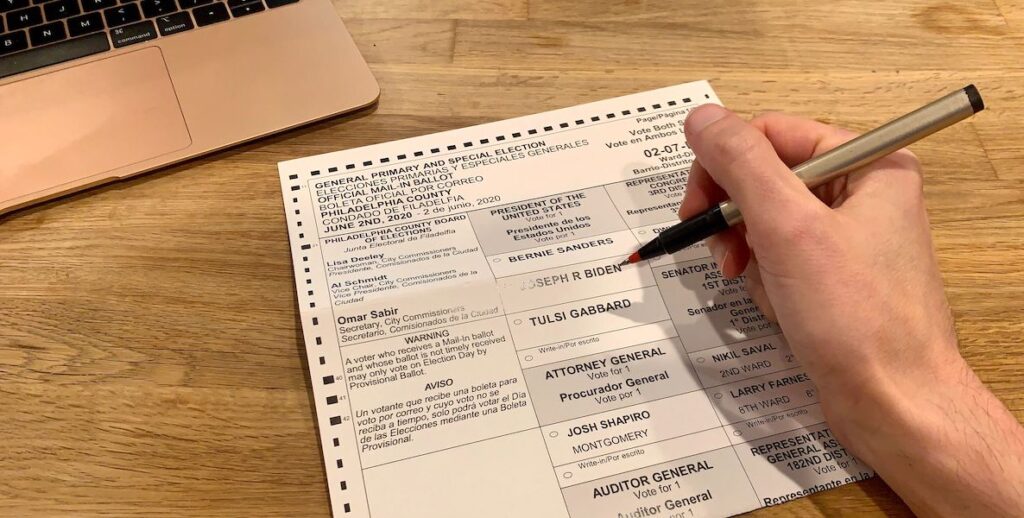

This year, though, voting will look different. I won’t be heading to the polls at all on June 2. Instead, I’ll take my time over the next couple weeks to browse the ballot that arrived in the mail today, and then send it off to the County Board of Elections—the first time in my life that I will have voted by mail.

That this is even possible is thanks to Act 77, the Pennsylvania law passed late last year that for the first time has allowed for no-questions-asked mail-in voting throughout the state—a dramatic change to the way we vote that happened just in the nick of time. Already, the pandemic delayed the April primary by six weeks; on June 2, Philadelphia will still be under state-mandated quarantine.

Gathering together to vote will be unsafe for all of us—not least of all the mostly senior citizens who work the polls. And the City Commissioners announced this week that they plan to only open 190 polling places in the city—rather than November’s 831. Which means potentially longer lines, larger crowds and dampened voter turnout.

Luckily, some 112,000 Philadelphians have already requested mail-in ballots, which is about 67 percent of the total primary turnout in 2012, the last time we had an uncontested Democratic presidential primary. But as Jonathan Tannen at Sixty-Six Wards has pointed out, those who have requested ballots tend to be younger, wealthier and whiter—not representative of either the city, or of would-be voters.

“Elections and the right to vote are foundational to our democracy,” Newsom said in a statement. “No Californian should be forced to risk their health in order to exercise their right to vote.”

As in California, this would not mean all Pennsylvanians would have to vote from home. It would just simplify what is likely to be a necessity for this year’s important general election—social distancing while voting.

Gov. Wolf has “encouraged” Pennsylvanians to vote by mail—but has not gone further than that yet. Right now, in order to get a mail-in ballot, Philadelphia voters must apply online, by letter or (when it’s open again) in person at City Hall by May 26. That is one more step, and one more date to remember, among many Pennsylvanians must go through to vote this year. (Registration deadline for the primary is next Monday, May 18, and for the general is October 19.)

Universal voting from home is not what the Pennsylvania legislature had in mind in the pre-pandemic days of 2019, when it passed Act 77, the most comprehensive voting reform in the state in a generation. (That law also shortened the time between registration and voting, something reformers had long clamored for.) Now, even before the first election since the change, Act 77 doesn’t go far enough.

“Elections and the right to vote are foundational to our democracy,” Newsom said in a statement. “No Californian should be forced to risk their health in order to exercise their right to vote.”

It perhaps goes without saying that this election year is a big one, as much for the country as for democracy. As pundits across the country will tell you, Pennsylvania is a swing state—that means, along with a few other battleground states, what happens here could determine who leads the nation for the next four years. That was also the case in 2016, when Donald Trump became the first Republican presidential candidate to win the state since 1988—by less than 1 percent, or just 44,000 votes.

Every vote this year counts, especially in the Philadelphia region, where the size of the population can easily sway the outcome—if we turn out to vote in much higher numbers than in 2016. Before the pandemic, that seemed likely: Turnout for the elections since then have been steadily higher than similar elections in the past.

Which brings us to the other advantage of mail-in-voting. In states across the country where they have universal voting from home, turnout is significantly higher than the norm in Philadelphia. Take Oregon, which 20 years ago became the first state in the country to conduct all of its elections by mail: In the 2018 midterms, 61 percent of Oregonians cast a ballot, compared to just 51 percent of Pennsylvanians.

That year, as in most, Pennsylvania ranked in the middle in terms of

And, despite claims by President Trump and the national Republican Party, voter fraud by mail is almost nonexistent—one reason why even the Pennsylvania Republican Party is encouraging its members to get home ballots this year and the Republican-led legislature allowed the reform in the first place. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, more than 250 million mail-in votes in all 50 states have been cast since 2000. But extensive research has found that “fraud rates remain infinitesimally small…it is still more likely for an American to be struck by lightning than to commit mail voting fraud.”

This, among many reasons, is why the Committee of Seventy (along with several partners, including The Citizen) this spring turned WeVote, a campaign to get all eligible voters in the state to cast a ballot, into a call for voting from home, if possible.

It’s not just that we don’t want to be the next Wisconsin, where the insistence on in-person voting last month may have led to an outbreak of cases. It’s that we want to make sure voting can happen at all. Even before the pandemic, the City Commissioners struggled to hire enough workers to operate the polls; with most of them being older residents who are especially encouraged to avoid crowds, the number of workers have dwindled even further.

To be clear, this will not be easy. County elections officials, including our own, have warned of the perils of mass voting by mail. For one thing, there’s the timeline: It can take two weeks for a ballot to arrive at your house after you apply. It must be returned to the County Elections office by 8pm on June 2—not postmarked June 2, but actually in the office.

And there’s no way to really know if it arrived unless you drop it off yourself. (Luckily, in Philly, the envelopes are prepaid, so at least we don’t need to get stamps.) All of which means, if you haven’t already applied for a vote-from-home ballot, it may be too late for this coming primary election.

And there is near panic over just how election officials will manage to count all the ballots, especially since the legislature will not allow counting to start until Election Day itself. (Even that is a concession: When Act 77 first passed, the law stated that officials could not begin counting mail-in ballots until the polls closed at 8pm)

With June 2 just around the corner, the massive amount of people voting from home may throw everything into chaos. It’s not likely that the City Commissioners have enough sorting machines to handle the volume, nor is there enough time to buy new ones. Already, the office strains to do what it’s charged with doing—ensuring Philadelphians can easily vote.

“Once you start playing out how this works, there’s some things you lose that you wish you wouldn’t—community, for one,” Thornburgh says. “But there are so many other things that it’s hard to argue it’s not a real improvement.”

“It’s a pressure test for a system that, generously, hasn’t worked all that well in the past,” says Committee of Seventy President/CEO David Thornburgh. “Are people going to get their ballots? Will they reach City Hall in time? How long will it take to count? We passed the law here without knowing we’d have a global pandemic, so without sufficient support.”

Commissioner Lisa Deeley assured the journalist Emily Bazelon in The York Times Magazine on Sunday that Philadelphia would be ready for November. The primary is another question altogether. While it may not be significant from a presidential primary standpoint (though of course there are state races to consider), it will be the first test of unfettered voting at home; if it is a disaster, the push for more home voting will be in jeopardy, as well.

In part, this is about expectations. In other parts of the country, Thornburgh says, votes are counted as they trickle in, perhaps for weeks; here, legislators worried that the count would leak and somehow affect turnout so didn’t allow that. We have become accustomed to getting election results on election night—largely, Thornburgh notes, because the news media insists on it. We may need to wrap our heads around the fact that that will be impossible on June 2, or even November 3—which means wrapping our heads around the fact that we may not know who will be our next president for some days.

It would also eliminate some of the inevitable ignorance that goes along with voting. Not sure what the ballot questions are really saying? No need to guess anymore; now you can go to the internet to find plain English explanations, arguments for or against, or even to ask your friends what they think.

Those who don’t know English can run the ballot through Google translate; those who find themselves anxious in the voting box, while others are waiting in line, can take a breath—and their time. It’s like taking an open book test instead of a standardized exam.

“Once you start playing out how this works, there’s some things you lose that you wish you wouldn’t—community, for one,” Thornburgh says—though he also suggests “voting parties” could become a thing. “But there are so many other things that it’s hard to argue it’s not a real improvement.”

After all, it isn’t where you vote that matters—it’s voting itself that makes the difference.

“My wife and I voted last night at the dining room table,” Thornburgh says, “and we’re never going back.”