Throughout my career, I have managed diverse urban schools with difficult learning environments—including a high school inside a prison. So I was up for the challenge in June, 2012, when the School District approached me to be the principal of Laura H. Carnell School in Oxford Circle.

And it was quite a challenge: Carnell was the largest elementary school in Philadelphia, and one of the largest K-8 schools in the state. When I took over the school’s leadership, enrollment within its three different buildings was nearly 1,800 students. The ethnic makeup was largely African American. The school had an English language learner population of 16 percent, and the special education population was around 10 percent.

It also was one of the lowest-performing schools, with a history of poor academic and organizational performance, and no significant student achievement for decades.

Achievement takes longer than growth. It is possible, and we will get there; but in the meantime, we should look at how much has changed for our students, not just how much is still failing.

Today, I lead a school much changed. But the successes—remarkable student growth that has put it among the top of its peer group—reflect a conundrum in the way we judge schools: Growth does not necessarily reflect real achievement among the majority of my students. But here in Philadelphia, we judge the success of teachers and schools on test scores. That is something we at Carnell struggle with every day.

The very first action I took as principal was to conduct a walking tour in the neighborhood to meet the residents, to get a sense of their perception of the school, and to meet the children and families who would make up the school community. I got an earful from the residents, to say the least. I met two very disgruntled mothers who politely, yet boldly, asked for change in the school and urged me to consider new ways for engaging parents.

![]()

Over the next couple years, we made significant changes to Carnell:

- Reconfigured the school from K-8 to K-5 during my first year, to establish a true elementary school, where we could focus on curriculum for that age group.

- Made program improvements, such as creating an Honors program, to increase the number of students performing at the proficient and advanced levels on the PSSA.

- Implemented an innovative, evidence-based redesign plan, as part of the School District’s Redesign Initiative.

It’s working. According to the School District of Philadelphia’s School Progress Report, Laura H. Carnell School is showing positive growth, the measure used by the District to determine success. In my first three years, the school improved its ranking from 86th to 18th when compared to all elementary schools in the city, including traditional public and public charter schools, and from 20th to 2nd when compared to 22 elementary schools that educate similar student populations.

But in our charged political climate, steady growth is not enough. Student achievement has become the sole indicator driving change in public opinion. The national storyline about low-performing schools fuels the growing demand to replace them with a “new system of schools.” The “new system of schools” is a portfolio of charter schools, private sector education companies, and new school models, as well as replications and expansions of “successful” schools.

I highly agree that many of these schools add value to urban education. However, it could also be that the “new system of schools” thrives on the strong economy surrounding failing public schools.

Low-performing schools tend to be the schools with the most pressing daily challenges. Learning spaces in these schools have been outgrown because of the buildings’ ages and sizes. Data trends ebb and flow daily due to enrollment policies that require these schools to accept students without delay, even during the PSSA testing period. Facility needs are insurmountable; some buildings go entire school years without classrooms being cleaned.

At the beginning of the 2015-2016 school year, 5 percent of our second-grade students were reading on target. By the end of the school year, 20 percent of them were reading on target. But look at the flip side: The other 80 percent of the second-grade students are still not reading at grade level.

Given all these factors, real achievement is a challenge that even schools like Carnell, that have shown significant growth, cannot easily surmount. A couple examples: At the beginning of the 2015-2016 school year, 5 percent of our second-grade students were reading on target. By the end of the school year, 20 percent of them were reading on target. This significant increase in one year would stand alone as a powerful performance measure for any school; it demonstrates success.

But look at the flip side: The other 80 percent of the second-grade students are still not reading at grade level. They are in need of intensive support, or at least a small strategic nudge, to get them on target.

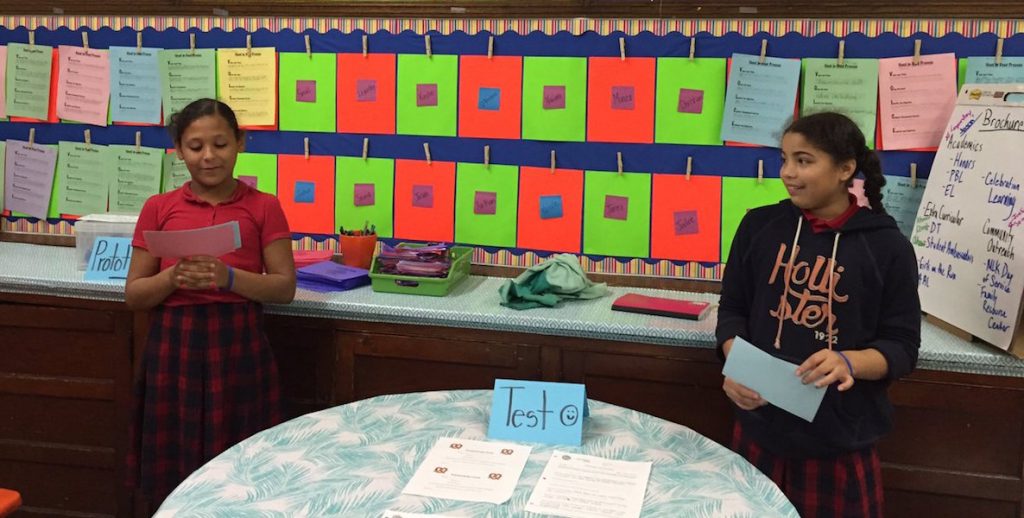

Consider another example: Throughout my tenure, we have implemented school-wide curriculum changes to increase student engagement and achievement, including prioritizing a project-based learning approach across the school, and conducting more and better professional development for our teachers. As a result, our students made gains in reading, writing, and speaking.

Ambitious systems for evaluating teachers and principals, and bold plans to reward or close schools are based on strict performance metrics—primarily PSSA scores. That’s why unrealistic achievement data always trumps growth data. The collective message to schools is clear: It cannot be fixed. It must be replaced or closed.

But as Carnell has shown, achievement takes longer than growth. It is possible, and we will get there; but in the meantime, we should look at how much has changed for our students, not just how much is still failing. If actual growth were emphasized over achievement data, schools that are in similar circumstances could breathe easier and focus on the important things—educating children.

Hilderbrand Pelzer III is the principal of Laura H. Carnell School in Oxford Circle. He won the 2014 Lindback Award for Distinguished Principal Leadership, and is the author of Unlocking Potential: Organizing a School Inside a Prison. Pelzer will be contributing regular columns from the school front lines this year.