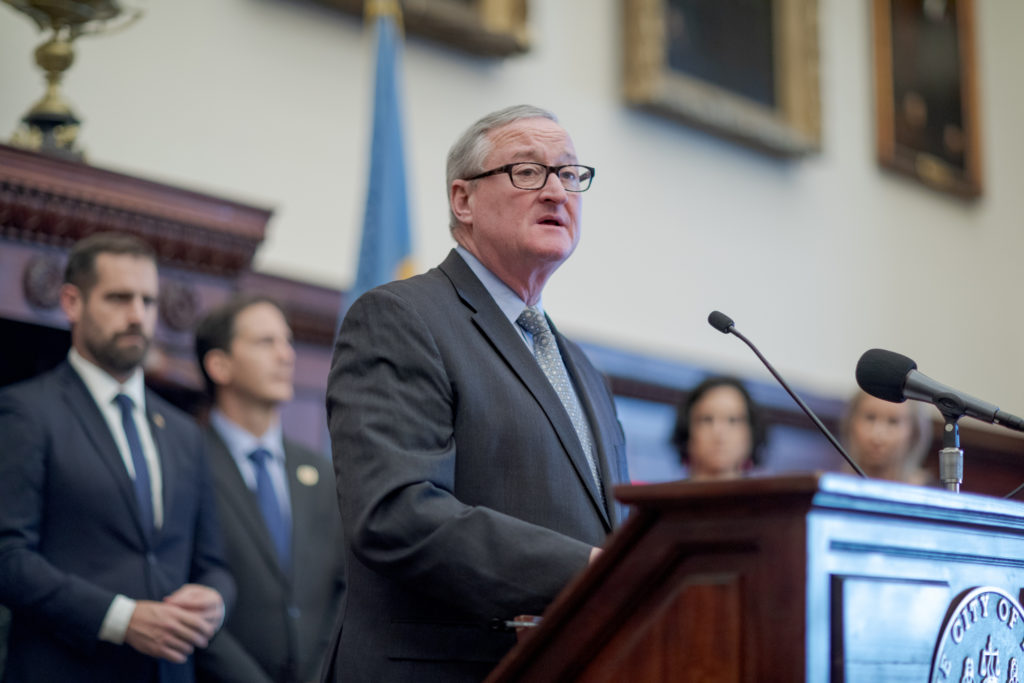

Mayor Kenney released his annual budget proposal Thursday, with a much more optimistic outlook for city services this year thanks to a major infusion of $1.4 billion in funding from the American Rescue Plan.

Under the Mayor’s plan, the budget would increase from $4.9 billion to $5.19 billion, with significant restoration of funding cuts from the pandemic budget in 2020, and also some significant new investments in key areas like gun violence prevention, workforce development, business tax changes, and maybe, just maybe, a mechanical street sweeping program.

Newly-minted blogger, attorney, and former 2nd District City Council candidate Lauren Vidas has a useful summary in her latest Broad and Market newsletter with the key highlights:

Without the $1.4 billion in federal resources coming to the city, the Mayor acknowledged that he would be presenting a very different budget. Instead, he has the opportunity to make investments, rather than cuts. Here are some of the bigger items coming out of today. Some of these investments are for this fiscal year, while others are spread through the course of the Five-year plan:

- Accelerated Wage and BIRT tax cuts

- $13.2 million to provide 911 operators with co-response and mobile crisis teams

- $250 million to Community College, with $54 million for the Octavius Catto Scholarship

- 700 new pre-K slots

- $1.38 billion in funding over the FYP for the School District

- $2.9 million to restore Library services, including after school programing

- $6.9 million to Parks and Recreation for pools and programming.

- $132 million to Streets Department in FY22 for repaving and ADA ramps

- $62 million over FYP for mechanical street sweeping.

- $750k in commercial corridor investment

- $5 million for various workforce development programs

- Additional resources for anti-violence programming and for safe space making (lighting, maintenance, etc.)

- $1 million for Opioid epidemic response.

Here are a few issues we’re eyeing right off the bat based on some of the usual topics we cover.

Investing in a More Competitive Tax Structure

Because of remote work and the implications for business location decisions, it is truer than ever that Philadelphia’s revenue system would be in sturdier shape relying more on taxing things that can’t move, like surging land and real estate values, and less on things that can move across taxing jurisdictions.

To that end, Mayor Kenney is proposing some modest reductions in tax rates for both wage taxes and the Business Income and Receipts Tax over the next five years. Laura McCrystal and Christian Hetrick report that the Mayor’s plan would reduce the wage tax rate for residents from 3.87 percent to 3.82 percent by fiscal year 2026, and for nonresidents, it would decrease from 3.5 percent to 3.4 percent, at a cost of around $83 million.

The plan would also make gradual reductions in the city’s business income and receipts tax (BIRT), which is unusual among U.S. cities for levying taxes on both business revenue and profits, and has long been targeted by economic development-minded tax reformers, like Paul Levy of Center City District, as an issue working against Philadelphia’s ability to compete for a larger share of the region’s jobs and business tax base.

This is significant because of the concerns that wage tax collections may represent a structurally lower fraction of the tax base going forward due to more non-resident workers shifting permanently to more remote work.

Before the pandemic, about 40 percent of total Wage Tax revenues came from non-resident workers. In 2020 and 2021, that number took a big hit. The Finance Department projects that up to 15 percent of suburban workers may never work from city offices again, but it’s possible that’s not really the right metric—it’s days spent working out of the city. If some suburban workers never return to city offices, and a lot more work from home at least a few days a week, that 15 percent estimate may be unreasonably optimistic.

The structural situation with wage raises the salience of regional tax base competition for residents and business locations. There are some dumber ways to join that competition and there are some smarter ways. Nobody should want to see a resurgence of the kind of desperate, negative-sum competition between local governments, where we’re awarding subsidies for relocations of various corporate headquarters.

But what we should all want to see instead is a set of competitive underlying conditions that make locating a new business in Philadelphia a better value than locating in the suburbs. And with a growing share of the workforce able to work remotely from anywhere, we’re now in a national competition for residential population that really points in favor of taking city residential quality-of-life issues more seriously than before.

To Councilmember Helen Gym’s pointed observation about this, there is so much more to the competitiveness picture than simply twiddling the knobs on different tax rates. One of the biggest challenges for growing Philadelphia’s residential population is the underfunding of public schools, and also the perception that the School District is poorly-managed as well—a perception that’s only increased during the pandemic. A thriving business environment necessarily requires strong local public schools, an educated and trained workforce, well-run and cost-effective local public services, a high-quality public transit system, and all kinds of other public goods that contribute to economic vitality and quality-of-life.

At the same time, it’s a mistake to write off tax reform as a piece of the puzzle, at a minimum because a significant structural downshift in wage tax collections on their own may require some other structural tax reforms. The tax differentials clearly matter on the margin for business location decisions within the region, and this is something we as a city have to pay attention to from a policy standpoint if we want to reverse the harmful trend of job sprawl throughout the region, which does great damage to the tax base, greenhouse gas emissions, transit ridership, and residential population growth in the city.

The Levy-Sweeney proposal, the subject of the last significant advocacy campaign attempting to reverse Philadelphia’s upside-down tax structure, never had the support it needed to pass as a state Constitutional amendment, especially once the Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce came out in opposition to it.

That amendment would have allowed Philadelphia to break from Pennsylvania’s Uniformity Clause in the state Constitution and set higher property tax rates on commercial properties than residential ones, as a way of financing a tax shift away from Business Income and Receipts and onto commercial property. That plan had some fair criticisms levied against it—many people, including Council President Darrell Clarke, didn’t like that the commercial real estate tax increases were officially wedded to BIRT cuts—and it was always at a disadvantage because it required a state Constitutional amendment to pass. It’s a very high bar to clear, and it likely won’t be tried again.

That suggests any future tax reform efforts would be better-off pursuing local-only changes, and to that end we’re seeing some interesting dueling proposals from Mayor Kenney in this budget and some separate legislation from Councilmember Allan Domb, co-sponsored by Mark Squilla, and Katherine Gilmore-Richardson.

As a practical matter, Wage is a tax that describes a few things at once. First, there are different rates for residents and non-residents. And for residents, there are actually two separate taxes that get mashed together and withheld from an employee’s paycheck under the name Wage Tax. About two-thirds of the Wage Tax is levied by the City. The other third—a flat 1.5 percent—lives with PICA, a government authority that was created to float bonds on the City’s behalf when we were dealing with a very real solvency crisis in the early 1990s.

Pew summarizes things nicely here, but it’s enough to know that PICA gets hundreds of millions of dollars in Wage Tax revenue because the City is still paying it back for the bonds.

To date, Wage Tax reductions have been almost laughably small, with most of the change happening three places to the right of the decimal. Despite nearly universal political support for Wage Tax reductions, the rate has only moved five-hundredths of a point in the last 10 years.

Currently, the total resident Wage Tax rate is 3.8712 percnt, which is the highest wage tax in the US. Of that, 2.3712 percent is City-side (see table) and the balance is imposed by PICA (1.5 percent). The non-resident Wage Tax was 3.4481 percent before the pandemic, but Mayor Kenney increased that to 3.5019 percent for the current fiscal year. That rate drops back down to the 3.4 number starting next year.

Mayor Kenney’s new plan is a five-year step-down, from 3.8712 percent this year to 3.8245 percent in fiscal 2026. Councilmember Domb’s plan goes further in terms of both the speed of the reductions and the time horizon over which it plays out. In his legislation, the rate in fiscal 2026 is 3.6768 percent, more than 4x the size of the Mayor’s cut.

That’s a considerable difference, especially in the context of Wage Tax reductions’ typically glacial pace. Additionally, Councilmember Domb’s schedule runs through FY2042, at which point the rate drops below 3 percent to 2.9000 percent. If we actually made it there, it would be the first time since the late 1960s that the Wage rate would be in the 2s.

The same trends play out in the BIRT plans proposed by the Mayor and Councilmember Domb. BIRT, or the Business Income and Receipts Tax, is made up of two totally separate taxes sandwiched together: the Net Income Tax, which is levied on profits, and the Gross Receipts Tax, which is levied on sales. BIRT has been the ire of local tax policy reformers for decades, since it makes the city an outlier for taxing both of those things—most cities tax one, if they tax businesses revenue at all—and for taxing profits at such a high rate.

Both Domb and the Mayor’s BIRT plans leave the Gross Receipts rate where it’s been for a while at 0.1415 percent but their plans for Net Income differ in ways that mirror their Wage Tax plans. The starting point on Net Income is 6.2 percent, with a scheduled reduction to 6.1 percent in fiscal 2024. The Mayor’s plan drops Net Income to 5.25 percent in fiscal 2025, while Domb’s plan puts Net Income at 4.92 percent that same year, but then goes all the way down to a flat 3 percent in fiscal 2031.

In addition to the Wage and BIRT bills, Councilmember Domb introduced a novel way to address the problem of taxing businesses on both sales and income, with a proposal that businesses would pay only the higher of the two BIRT tax bills. This might not be a long-term fix, but in the short term it meets businesses where they are and targets the part of their books that are strongest.

Interestingly, this proposal might provide a politically safer landing place for those members of Council who want to do something to support businesses—especially as many carry considerable debt accrued during the pandemic—but feel squeezed by skeptics of the proposed Net Income cuts.

Mayor Kenney’s Finally Funding Street Sweeping

We’ll believe it when we see it. But it looks as though Philadelphia is finally going to get a citywide street sweeping program at a real scale.

Mayor Kenney is proposing to spend $62 million in the Five-Year Plan—about $12.4 million a year on average—on a mechanical street sweeping program that will at first prioritize more Black and Brown neighborhoods where the most illegal dumping has been documented. Before the pandemic, the Mayor proposed spending $10.5 million a year on street sweeping at the beginning of the year, but that was canceled when the economic situation worsened and revenues cratered.

The Kenney administration won’t say yet when the program might start or what neighborhoods could see sweeping service start in the first round, but Ryan Briggs was able to find out some of the details for PlanPhilly:

Following a WHYY News feature revealing the city rarely swept a handful of streets that still received nominal cleaning, Kenney sent millions into upgrades for its neglected sweeper fleet. Initially, the city experimented with using leaf blowers to dislodge litter without moving cars, but switched back to a strategy of traditional street cleaning after some public controversy.

As planned before last year’s budget cuts, the program would cost about $10 to $11 million annually, with an eventual objective of expanding beyond initial pilot zones. Kenney reiterated in his budget address that the city still intended to ask residents to move their cars in order to clear a path for sweeper trucks.

Beyond that, details are still fuzzy—including a possible timeline for rollout.”

Those who have long been following the twists and turns of the street sweeping debates with us, via this newsletter and elsewhere, will recognize the significance of a few of these details.

For one thing, the leaf blower pilot seems fully dead. Though anecdotally, some people still report seeing the leaf blower crews out sometimes around South Broad Street and other parts of South Philly, but it’s unclear what that’s all about. What we do know is that the leaf blowers are slated to be part of this program, and the Kenney spokespeople are specifically using the words “mechanical street brooms” and “trucks” to describe the program.

Managing Director Tumar Alexander also told Briggs, “It’s basically intensive street cleaning with increased laborers and mechanical street brooms in certain targeted neighborhoods.”

Longtime readers will recall that the staffing levels are a key issue to get right because they have a direct bearing on whether or not this can become a universal program, or if it’ll always remain small and targeted like this early pilot. Back when Managing Director Brian Abernathy cooked up his leaf blower workaround, you would sometimes see 7 or 8 people with the leaf blower rigs working on a single block at any given time. That’s the type of thing you’d do if you had no intention of ever making the program universal. A better goal would be to hire the same number of people, but have each person drive a sweeper truck, with the aim of hitting every block in the city once or twice a month instead.

The early financial commitment is in the range of what’s needed to run such a program with small crews, based on earlier reported figures about the cost estimates of sweeping the whole city once a month. But it’s still unclear from the announcement whether the Mayor really intends to stand up a program like that by 2023, or whether that task is going to fall to the next Mayor.

Either way, street sweeping supporters can feel good about the moral victory we’ve won over the first six years of the Kenney administration, even while maintaining some healthy skepticism about the execution. The issue is on the political agenda, it’s in the Mayor’s budget, and it’s getting some real funding this year.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.