For too long, children of color were more likely to open a book and see a main character who was a talking piece of fruit than someone who looked like them.

But the quest to present children of color with a diverse array of protagonists has gained momentum over the last few years. Marley Dias’ #1000BlackGirlBooks helped the movement go mainstream in 2015, and authors, activists, parents, and kids have continued to fuel the creation of even more stories with main characters who are black.

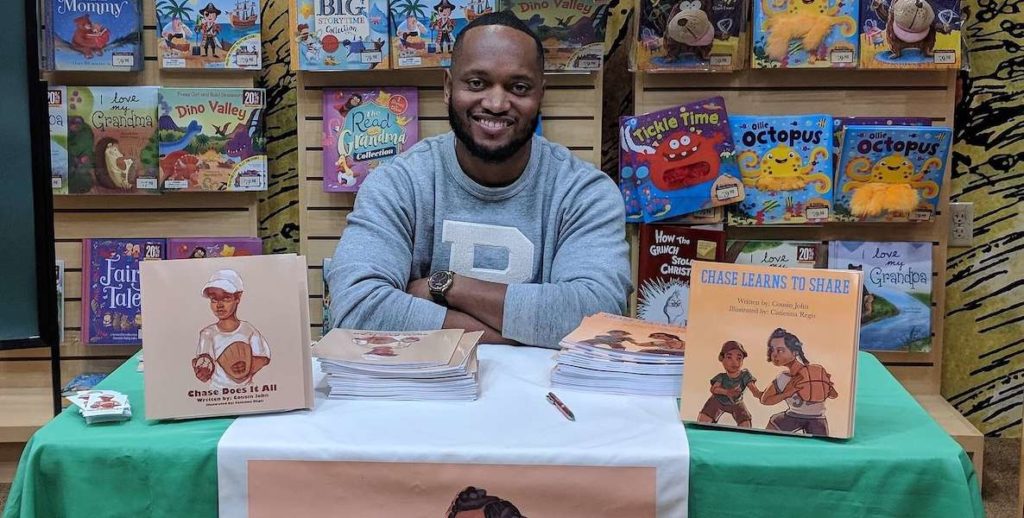

Philly native John Butler, a sports editor for Comcast Interactive, is among those authors doing his part. His creative process began over three years ago when searching for a book featuring a character of color for his soon-to-be-born baby cousin, and coming up empty.

![]()

“I was like ‘Alright, well I’m accustomed to writing, so I’ll write a story for him,’” says Butler. And that’s how the Chase series, named for his cousin, began in 2017: in the spirit of bringing children of color to life, and fueling childhood literacy.

Here, Butler talks about the importance of diversity and inclusion in children’s literature, and the world.

Kiersten Adams: When you first started writing the Chase series, what did the children’s genre look like to you?

John Butler III: I started to do my research and people would say, ‘Hey there’s this book, and there’s that book’, and they were cool. A lot of them told historic stories. We need that, but what about the child who’s trying to figure out his world? So I think that the stories about our past and the cultural importance we’ve had are great, but there are children in school all day reading books about kids who don’t look like them. So they’re automatically assuming they can’t do the things those children are doing in those books.

That’s why my first book was called Chase Does It All. I wanted children to understand that you can literally do anything and everything you put your mind to. And I write about simple activities they can relate to: playing baseball, eating ice cream, getting pizza, hanging out with family and friends.

KA: As a sports journalist, what was the transition to writing children’s writing like for you?

JB: The transition was interesting because they’re two completely different audiences. I can’t write for a six-year-old about points-per-game, rebounds, stats, and metrics of that nature. So it took me to a new place in that I hadn’t necessarily been using my imagination and my creativity in that way.

KA: What books from your own childhood do you remember best?

JB: Ironically, it wasn’t a children’s book. It was The Fab Five by Mitch Albom.

Any time that you can express to a child that there is so much available to them, as long as they’re putting their effort forward in school, and just being the best person they could be, those are things I’m really hoping to accomplish.

If I couldn’t get the books that were for children, the only sports books I could read were the books my dad had. That’s how I got to The Fab Five book by Mitch Albom. Albom wrote for The Detroit Free Press so it was written on that level. And I read it because it was the only thing available to me that I had an interest in at that time.

KA: So you didn’t care about the reading level as much as you did about the material?

JB: I saw my dad reading the newspaper at the time and he would read these sports biographies, so organically I started to pick up [those] books as well. The idea of reading about characters who look like me—to be honest it wasn’t something I realized I was doing until I started writing children’s books and having these conversations with children at book readings and story time events. I didn’t even think about it at the time, but obviously that played a significant role in the selection of books I choose and even the selection of my career path.

KA: Understanding the importance of representation, why do you think it’s crucial to center black childhood in your books?

JB: I think that age and that innocence of being a child and being able to view the world from that amazing lens helps to determine what our societies are going to look like in the future. So let’s not rush them into this world of adulthood and extreme content. Let’s provide them with an opportunity to grow, to learn, and to make the world a better place.

If I can do that by writing a book where they can get interested in just being a child because they’re seeing the illustrations of children playing and joining forces to share and do things like meeting new people, I can do my part in feeding those tidbits of life lessons, and I couldn’t ask for anything more.

KA: Do you feel like children’s books today are more diverse than in the past, or have we plateaued and settled for tokenism?

JB: I think the representation is growing—and that’s great and I love it. There are never going to be too many people writing books for children that look like us because we’re all different, we all have different needs, we all relate to different topics and subjects. I love the fact that I see the space growing, I love that I see new writers and illustrators coming into the space as well. It’s something that lets me know I have to keep doing the work that I’m doing with writing new books

KA: What effect do you think this book will have on those kids who are seeing themselves reflected in your work?

Any time that you can express to a child that there is so much available to them, as long as they’re putting their effort forward in school, and just being the best person they could be, those are things I’m really hoping to accomplish.

JB: With the new book coming out, Chase is Ready for Takeoff, it tackles a few different things. Specifically, I wanted children to be comfortable formulating the idea of how do you overcome fear? In the story, Chase is scared to fly and get on a plane, but because he overcomes that fear, he is able to experience a lot of amazing things in life. So a child’s fear may or may not be flying but they might have a fear of speaking in public, or raising their hand in class, or meeting new people. The quicker that we can address these things, the quicker we can overcome them, and experience a much more fulfilling life.

It’s also important for children, particularly the children I encounter through reading, story time, and things of that nature, to understand that I come from the same exact neighborhood that they do. So I make a point whenever I talk to children to say ‘Hey, I’m from Philadelphia too. I grew up five minutes from here. I went to the same pizza store that you go to everyday.’ Any time that you can express to a child that there is so much available to them, as long as they’re putting their effort forward in school, and just being the best person they could be, those are things I’m really hoping to accomplish.

I read my story Chase Learns To Share to a class of first-graders. And one of the students raised his hand and asked ‘Why are the people in that book that color? They’re brown, why?’ So I said, ‘Well what color are you?’ He goes, ‘I’m brown.’ I said, ‘So am I, and so is Chase in real life. So that’s why. His response to me was ‘I did not know that you could do that.’ So you can’t tell me that it’s not important to have inclusion when there are people that don’t feel as though they should be represented in the stories that they’re reading that are meant to teach them how to read.

KA: What does the future of children’s lit look like if others follow your model of sharing diverse stories or centered blackness?

JB: If you look at some of the issues we have in our society, where people are being undervalued or people aren’t being treated fairly or people are being underrepresented, I think you eliminate all of those issues if children are reading books that feature inclusion.

If you’re in the second grade and you’re a white child, but you’ve read books that feature African Americans, you’re not surprised, uncomfortable, acting inappropriately when you go to a high school class or a college class. When you’re seeing these people, it’s not the first time you’re seeing or being able to relate to these individuals. You’re able to have conversations about race, it introduces those things to you. Like ‘Hey, my favorite character in the book is Chase. I might not have a student in my class who looks like Chase, why?’ You can begin to have those conversations on a level children can understand.

Interview has been edited and condensed.