There has been a lot of smart commentary about the meaning of this week’s election day. Observers have noted that the post-2016 winds of change first seen in last year’s election of Controller Rebecca Rhynhart and District Attorney Larry Krasner continue unabated. Our congressional delegation has the chance to send as many as five women to Washington, D.C., up from, well, zero. Old-school silos of political power, ranging from labor leader John Dougherty to African American power broker Marian Tasco, whose hand-picked candidate failed to topple State Representative Chris Rabb, both took it on the chin. Suddenly, grassroots populism is in—in a city (Moscow on the Delaware) not known for competitive elections.

Be Part of the Solution

Become a Citizen member.What hasn’t been much discussed yet is what all this means if you’re the Mayor. Jim Kenney blanketed the TV airwaves with ads for his hand-picked congressional candidate, Rich Lazer, his former right hand man and another Dougherty acolyte. When the congressional map was redrawn by the State Supreme Court, Lazer’s district was split between South Philly and Delaware County. That meant that, to win, Lazer would have to take about 70 percent of South Philly. In the end, he didn’t come close to that and finished well behind Delco candidate Mary Gay Scanlon.

Is it possible Kenney is misreading the political moment? Strictly from a political strategy standpoint, each time he talks about raising taxes, sanctuary cities or safe injection sites, might it be that vast numbers of Philadelphians are feeling like he’s not on their side?

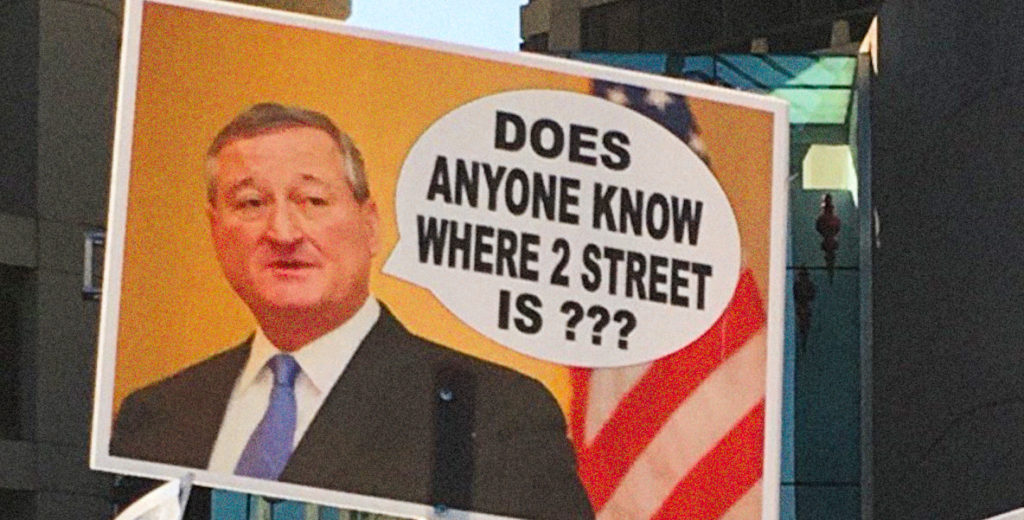

South Philly is Kenney country, no? It’s where he grew up, where his father was a firefighter, where he delivered the morning Inquirer, where he marched in the Mummer’s Parade. South Philly should be his base. Yet, candidates who were knocking on doors in South Philly say they were surprisingly confronted by opposition to the Mayor’s policies. Among the complaints: the soda tax, out-of-nowhere property reassessments, the moving of the Rizzo statue, sanctuary cities, visiting Meek Mill in prison. That anecdotal evidence, combined with the rejection at the polls of his hand-picked candidate, should have Kenney worrying whether he’s neglected his own natural constituency.

Prefer the audio version of this story? Listen to this article in CitizenCast below:

It was smart politics. But actually governing and keeping such a fragile coalition together is harder, as he just now may be finding out: There are complaints in the African American community about a perceived lack of diverse hiring in the Kenney administration, and now Council has concerns over the diversity-in-hiring commitments Dougherty and the Building Trades have made for Kenney’s pet public works project, Rebuild. Meantime, even the urbanists are getting antsy, carping, for example, about the slow pace of protected bike lane rollouts.

Kenney has spent significant political capital—and real capital—on the airwaves for only two political campaigns: Lazer and Attorney General candidate Steven Zappala, and he’s lost both. His support for Zappala was seen by most observers as payback to Dougherty, who pushed hard for the candidate who ultimately lost to Josh Shapiro. Make no mistake: Kenney remains joined at the hip with Dougherty, who, as far as anyone knows, is still under federal investigation and who is on a losing streak of his own, with Zappala’s and Lazer’s losses sandwiched around the washout in the D.A.’s race of babyfaced Jack O’Neill.

Is it possible Kenney is misreading the political moment? Strictly from a political strategy standpoint, each time he talks about raising taxes, sanctuary cities or safe injection sites, might it be that vast numbers of Philadelphians are feeling like he’s not on their side?

Leading would mean finally speaking out on the scandal of the city’s missing millions, and the fact that his administration has let something like $40 billion go through bank accounts that haven’t been reconciled in years.

This is not to suggest that Kenney ought to alter his position on any of those issues, or any others. But go back in time. When he was Mayor, Ed Rendell was able to take progressive stands—inviting Minister Louis Farrakhan to Philly during racial unrest comes to mind—at the same time that an overwhelming number of citizens, black and white, felt that he had their back.

Contrast that to Kenney, who seems to not have met a tax he doesn’t fall in love with. Yes, he laudably took back control of our schools, but he did so without leveraging that move for more state support, leading to the obvious question: Was this merely a case of paying back the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers? With the school district facing a structural deficit, we are now following the soda tax with another proposed property tax increase—which, incredibly, comes at a time when property assessments are skyrocketing. No wonder candidates in South Philly were confronted by voters who saw the Mayor visiting Meek Mill and seemed to wonder: “Does he care about me?”

There are complaints in the African American community about a perceived lack of diverse hiring in the Kenney administration. Meantime, even the urbanists are getting antsy, carping, for example, about the slow pace of protected bike lane rollouts.

Even with what might be soft support in the electorate, it’s unlikely Kenney will be challenged in 2019. Things may be changing, but we still might be in the last vestiges of The People’s Republic of Philadelphia. So Kenney could conceivably hang on to the old way of doing things and be reelected. But he may be more vulnerable than he appears. Kenney won election in 2015 with all of 129,000 votes in the primary and 200,000 in the general election, with only 25 and 27 percent turnout of registered voters, respectively. With an amped up electorate…who knows?

But that doesn’t just mean telling disparate interest groups what they want to hear. It also means deciding to lead. Leading, for example, would mean levelling with Philadelphians—not, say, trying to hide how much it cost to throw the Eagles parade. Leading would mean sitting down with your morning coffee and reading the Inky’s report on just how many kids are going to school in toxic environments and telling the superintendent to fix it now—and then telling residents the plan so we know he’s got it covered.

And leading would mean finally speaking out on the scandal of the city’s missing millions, and the fact that his administration has let something like $40 billion go through bank accounts that haven’t been reconciled in years. He could admit that, by violating its fiduciary responsibility to the taxpayer, his administration has squandered the credibility for yet another tax hike. He could tell Council: “I’m rescinding all tax proposals until we can guarantee taxpayers that we’re going to be responsible stewards of their money.” He could do as Spokane, Washington Mayor David Condon did last year, after his city went through successive annual audits that found material weaknesses in its accounting practices; “I wish you the very best in your future professional endeavors,” he wrote to his Director of Accounting, before cleaning house.

He could, in other words, put the average, tax-paying citizen first. If you’re Jim Kenney right now, you’ve got to be concerned that your electoral coalition might be fraying. If you level with your citizens, chances are they’ll give you a mulligan.