Back in November, I found myself at a dinner party with 20 or so of the region’s most accomplished business movers and shakers. One attendee estimated that the net worth of the room was in the billions. (Obviously, my presence significantly brought down the curve.) As the conversation ebbed and flowed, a common theme emerged: Concern for the economic future of the city. And puzzlement over the Mayoral vision, a year into the new administration, for how to grow the local economy.

“It’s been a year, and all we’ve been hearing about is ‘soda tax, soda tax, soda tax,’” said one macher. “Well, I support pre-K. But where’s the economic development plan? How are you going to grow jobs?”

Others agreed, and soon the room was full of commentary attesting to the city’s lack of business friendliness. There were complaints about our status as the highest-taxed big city in America this side of Bridgeport, Connecticut, and about the inaction of our elected officials: “The only time I hear from a politician is when he wants a check,” someone said. Then came a rundown of a string of recent laws—ranging from paid sick leave to the ban on employers’ asking about applicants’ salary histories to the speculation that Councilman Bobby Henon will soon be introducing paid family leave legislation. We have to compete for talent and market share with our surrounding suburbs, I heard time and again; unilateral laws like these render us uncompetitive. A tipping point may have been reached earlier this week when Dan DiLella, President and CEO of Equus Capital Partners, announced that he was taking his 135 employees to Berwyn—in part, due to the city’s challenging business climate.

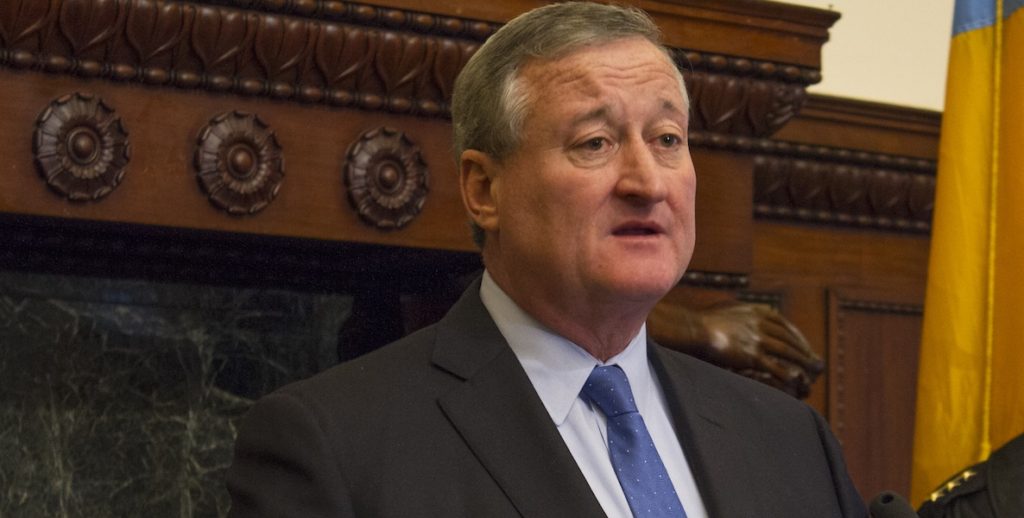

Our dinner party Masters of the Universe were all doing quite well, and had been for some time. Yet they shared a concern about the trajectory of Philadelphia’s story: low growth (of the top 10 major cities, we rank ninth in economic growth at a paltry 1.9 percent), high taxes, high poverty, struggling schools. In the year since Jim Kenney’s election, where was the plan to grow jobs? Where was our new story?

Worldwide, cities are having a moment as engines of innovation; my impression has been that Mayor Kenney has been incurious about that trend, attached instead to old school tax and spend, redistributive policies. His signature year one accomplishment, after all, was the soda tax; not once did the Mayor tell the taxpayer what the return on that investment would be. Would it cause the graduation rate to increase 13 years from now? By how much? He posited pre-K as long-term economic development…well, cool: What’s the goal for how many jobs we derive from this tax? In other words, how do we judge success?

We were never really told. In fact, we weren’t even told during Mayor Kenney’s job interview—the campaign—how he’d pay for pre-K. Back then, you’ll recall, it was to be funded by zero-based budgeting, a truly inventive idea that would have placed the city at the forefront of urban innovation. Once in office, though, that reform morphed into the soda tax.

That’s why I eagerly awaited Mayor Kenney’s second annual address to the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce last week. Would he drop a new vision on us?

Sadly, no. What we got was more of the same. Yes, there was the recap of the Mayor’s two big ticket investments, the pre-K program and Rebuild, the administration’s $500 million investment in parks, libraries and rec centers. And, yes, there are green shoots of disruptive thinking in Kenney’s government, like Startup PHL. But Kenney’s Chamber speech was mostly a recitation of small-ball policies—L&I’s cutting in half the time it takes to process permit applications, the Commerce Department’s Capital Consortium of lenders that have made four loans totaling $385,000—and announcements of plans to study issues like “transportation and planning” in order to take action at some point down the road. The speech wasn’t devoid of content, so much as lacking an animating idea that might lead you to say to yourself: “Wow. Someone’s rethinking who and what we are.”

In effect, as last week’s speech illustrates, Jim Kenney is an old-time big city mayor who believes in redistributing wealth. Problem is, given our tax base, there’s precious little to redistribute. What the times call for is a vision that neither seeks to tax and spend or cut its way to growth. Rather than slicing more pieces of an ever-shrinking pie, we need to grow by changing what we think about city government, and the role of the mayor in it. That’s what the most cutting-edge cities have done, as The World Bank’s 2015 Competitive Cities report found.

In a study of 750 cities that outgrow their home countries, the World Bank concluded that all share these traits: “(a) business leaders were consulted about their needs and the constraints they encountered in their operations; (b) infrastructure investments were made in collaboration with the firms and industries they aimed to serve; (c) skills initiatives were designed in partnership with firms, ensuring that curricula addressed their practical needs; and (d) industries were supported where they had a real commercial potential, through collective initiatives with the private sector rather than through the public sector alone.”

In other words, rather than piling more taxes and regulation upon businesses, forward-thinking urban leaders have learned to partner with them. That might not play well on the political Left, where outrage over crony capitalism tends to obscure what pro-growth mayors in our fastest-growing cities have long known: Their citizens won’t have jobs without the businesses to hire them.

So what if Mayor Kenney announced that Philadelphia was going to unleash the genius of capitalism to help cure our problems? That would require widening the aperture of his lens and getting beyond our usual zero-sum debates. Just imagine if his pro-forma laundry list before the Chamber included some of these ideas:

The City of B Corp Love. Philadelphia is already arguably the most B Corp friendly city in the nation, but few know it. Here’s the background: Berwyn-based nonprofit B Lab created a new type of company, the B Corp, which extends members’ fiduciary responsibility beyond just shareholders, to stakeholders such as employees, the environment and the surrounding community. B Lab confers a type of Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval when it comes to social responsibility for its more than 2,000 member companies, including well-known brands such as Patagonia and Ben & Jerry’s.

Marketing Philly as the B Corp city would set us apart, sending a much-needed signal that private sector bottom line success and civic health needn’t be at cross purposes. Already, thanks to then-Councilman Jim Kenney, Philly is one of the few cities to give companies a B Corp tax break. Expanding it would also be a way to attract and keep millennials here: “All of the startups that come see me?” venture capitalist Richard Vague once told me. “It’s a settled issue for them. They’re B Corps.”

Greenlight Governing. Why is it that Pittsburgh is the testing ground for Uber’s experiment with driverless cars, while Philly only recently okayed the use of ride-sharing? In part, it’s because Mayor Bill Peduto practices the art of “Greenlight Governing”—and Jim Kenney should do the same. Peduto did more than pay lip service to his city’s burgeoning startup community. He went out of his way to give them the freedom to experiment…and even fail.

“It’s not our role to throw up regulations or limit companies like Uber,” said Peduto. “You can either put up red tape or roll out the red carpet. If you want to be a 21st Century laboratory for technology, you put out the carpet.” Peduto has given Uber unprecedented free rein, including exemptions from regulations. You want to attract talent? Let it be known that you’re a city that will let it flourish.

Be The Convener-in-Chief. The old way of being the city’s chief executive uses the power of your office to reward friends and punish enemies, and to prescribe solutions from on high. The new way is to invite others to join you at the problem-solving table.

Rather than piling more taxes and regulation upon businesses, forward-thinking urban leaders have learned to partner with them. That might not play well on the political Left, where outrage over crony capitalism tends to obscure what pro-growth mayors in our fastest-growing cities have long known: Their citizens won’t have jobs without the businesses to hire them.

Case in point: Every couple of years, headlines are made because, unlike in other cities, our nonprofit universities don’t pay a set fee to the city as a Payment In Lieu of Taxes. The debate rages for a few days…and then fizzles out. Well, how about we move past the predictable back and forth and, instead, Mayor Kenney brings the presidents of the city’s universities into City Hall and tells them the issue is settled: They’ll never again be asked to pay PILOTs. Rather, he’s inviting them to partake in a new challenge—call it Solutions In Lieu of Taxes, whereby each institution deploys its arsenal of intellectual talents and its resources to develop new answers to the intractable problems that plague us beyond the borders of its own campus.

This idea of government convening the best and the brightest to work for the common good is already making inroads elsewhere. In Dallas—one of the fastest-growing local economies in the nation—numerous stakeholders have come together to form the Dallas Innovation Alliance, a nonprofit public-private partnership recognized by the White House for turning Dallas into a smart city. Corporations, private sector firms, nonprofits and government officials have all worked together to make Dallas a hotbed of innovation and economic growth strategies. For Philadelphia, what might be most innovative about the Dallas Innovation Alliance is the simple idea of the business community and government working so closely together.

“In Philadelphia, there’s a history of outsourcing leadership to local government,” says Professor Richardson Dilworth of Drexel’s Center For Public Policy. “Public-private partnerships like in Dallas can offer us a way to get all key stakeholders to sit at the problem-solving table together.”

To be clear, the idea of widening the net of problem-solvers isn’t just about adding more voices to our civic conversation. Social impact, or pay-for-success, bonds have actually been used by governments to pay for public policy programs. In this model, the private sector works with governments and philanthropies to fund social programs—and investors only see a return once clearly defined social impact goals are met. This type of collaboration with the business community stands in stark contrast to how Philadelphia has long approached governing, with an emphasis on broad-based taxing and stringent private sector regulation.

Think Huge. Finally, perhaps the most important thing Mayor Kenney can do to jumpstart the local economy is to think more ambitiously, to summon JFK’s audacious call to put a man on the moon in 10 years. People want to be inspired. So what can Jim Kenney’s moonshot be? I’ve argued before that it ought to be high-speed rail in the Northeast Corridor. The timing may be fortuitous, now that we’ve got a president who, despite some odious thinking in other respects, says he wants to pass a $1 trillion infrastructure bill. Kenney should convene a broad-based coalition that lobbies for a resurrection of Amtrak’s $150 billion 2012 plan for high-speed rail.

Thirty-seven minutes from 30th Street Station to Penn Station? What would the economic impact be of that? It would make our city a bedroom community of New York, which would grow jobs, real estate values and tax revenue. For those who worry that such an eventuality would lead to a type of Upper East Side-ification of Center City, that’s a justifiable concern worthy of study. But the fact remains that the type of incrementalism and outdated thinking outlined in Mayor Kenney’s Chamber address doesn’t align with the pressing needs of this moment. You want to finally adequately fund our schools? Make a dent in the poverty rate? Grow jobs in every neighborhood? Address the pension crisis that, left unchecked, will only further drain education and infrastructure spending?

Well, think big, Mr. Mayor. Because only after you grow, can you then redistribute.