Around the time last week that Jeff Brown, the entrepreneurial grocer who has brought fresh food and healthy lifestyle choices to Philadelphia’s food deserts, was opening his latest and boldest store — a Fresh Grocer in Wynnefield Heights that is a type of affordable Whole Foods for a diverse urban neighborhood—the Mayor was nearby, taping Channel 6’s Sunday morning public affairs show, Inside Story. And he was taking direct aim at Brown.

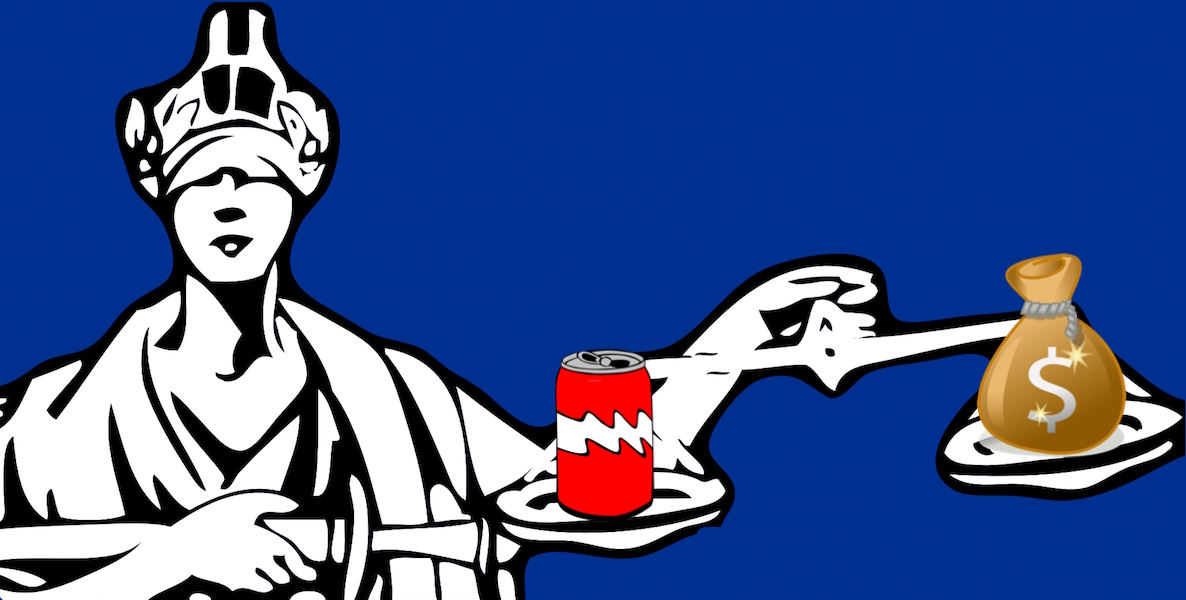

PepsiCo had just announced plans to cut 80 to 100 jobs, owing to the effects of Kenney’s soda tax. In response, Kenney seemed Trump-like to question the motives of his critics. He claimed that the soda industry was playing politics with its workforce and laying off people to make a point: “PepsiCo has sunk to kind of a new low,” he said, referencing Pepsi’s profits — despite the fact that his tax is aimed at distributors.

Then he set his sights on Brown, whose six inner-city ShopRite stores have over the past decade brought affordable, fresh, healthy food to low-income neighborhoods, not to mention in-house nutrition counseling, and health and social work services. President Obama once highlighted Brown’s work in a State of the Union address, holding it up as an example of how forward-thinking public/private partnerships can lift up indigent communities.

But now the Mayor was publicly doubting Brown’s intentions. Brown had recently spoken out against Kenney’s soda tax. Sugary drinks, it turns out, only make up 4 percent of Brown’s bottom line; he could withstand its 40 percent decline in sales. But, so far, when his customers cross City Line Avenue to get soda, many are also doing all their shopping there. So Brown’s stores are down 15 percent overall, in a business famous for its tight margins. That’s not sustainable, he says; he’s already had to cut between 5,000 and 6,000 hours of employment each week, the equivalent of 280 jobs. If things continue, he may have to join PepsiCo and lay off workers.

You might think a Mayor would react to job losses that are a direct result of his tax policies with some introspection and some platitudes about how any one job loss is one job loss too many. But so far that has not been Jim Kenney’s reaction. On the night PepsiCo announced its layoffs, the Mayor’s team rushed out a press release, detailing that the city’s Pre-K program had created 191 teaching positions, 147 of which are full-time, at an average wage of $14.72 an hour — hardly equivalent to the unionized jobs with full-time benefits imperiled by the tax.

And then Kenney took aim at Brown on Inside Story, suggesting that, like PepsiCo, Brown was crying wolf: “From the retailer side, guys like Jeff Brown, he just opened a store inside the city limits,” Kenney said. “He’s talking on one hand about cutting employee hours, and on the other hand he’s opening a new store.”

Politically speaking, the Mayor has done a deft job of making “Big Soda” into a modern-day “Big Tobacco” — cold, greedy, profiteers who exploit his constituents for private gain. But now that Brown is speaking out, Kenney might have met his match. Brown is harder to vilify than a giant soda company — because he’s actually been servicing Kenney’s voters for years, and because he’s been working on inner-city social justice issues just as long. Spend any time in his stores — or watch this 2015 PBS clip — and it’s clear that Jeff Brown is as woke a white dude as this city has seen:

I caught up with Brown last week at the new store in Wynnefield. He’s a big, garrulous man, and I found him in the beer and wine department, greeting well-wishing customers with warm embraces. He was quick to show off the store’s 700 varieties of beer and wine; “Who else has a Sake department?” Brown beamed, pointing to the options of Japanese rice wine, not far from the Kosher wine section, certified by an in-house Rabbi. Nearby, a line formed for chicken that was crackling on an open grill, Muslim shoppers crowded around a Halal-approved meat section, and, in front of an open-seating space, a young woman strummed a guitar and sang mellow tunes into an open mic.

As I toured the store, two older black women approached me near a Pepsi display. “Do we pay the soda tax for this, or do we need to go to the Acme?” one asked, referring to a store across City Line Avenue. I pointed them to the far corner of the store, where rows of drink products were arranged under large signs reading “NO PHILLY BEVERAGE TAX ON THESE ITEMS.” These were the unsweetened flavored waters, seltzers, fruit-based drinks, powdered drinks and 100 percent juices not subject to the tax. Is this Brown sticking it to Kenney?

“As an entrepreneur, I work for my customers — my job is to come up with solutions that help them,” Brown says. “So we separated our Philly sweetened beverage items into those that are taxed — they’re in an aisle and the tags clearly indicate what the tax is—and we were able to get all the items that are not taxed together, too. We have a responsibility to help our customers out. Shopping here could be a strategy for a household to keep their costs down.”

That’s why, though the feel of Brown’s Fresh Grocer might be Whole Foods-like, the prices are significantly lower. “We’re trying to do more of an upscale environment at a lower price point,” Brown explains. “Oddly enough, cheaper accelerates volume. We’re finding that cheaper prices for high quality products can actually have a better bottom line than expensive prices.”

Brown has long been able to make the numbers work thanks to innovative public/private partnerships that help him handle his costs, a fragile algorithm now imperiled by the soda tax. Brown took advantage of the Fresh Food Financing Initiative, a collaboration between the state and the Reinvestment Fund (full disclosure: Citizen Chairman Jeremy Nowak was the founding CEO of the community development institution) or nonprofit lenders; with minimal investment and risk, public outlays have helped defray the cost of higher quality food. Left to its own devices, after all, we know what the free market had wrought for the inner city: Artery-clogging fast food spots and junk food-laden Dollar Stores.

As a result, Brown has long been a sophisticated political player, a donor to politicians like Jim Kenney. Is it strange to have served the city, and now find yourself at odds with its elected leader? “What I’m guilty of is being loyal to the residents of this city,” Brown says. “The city itself asked me to do this and after asking me to do it, after I invested an enormous amount of money in the city, more than anyone, while a lot of my competitors stayed in the suburbs saying the city is too risky, the city has now created an environment that might make a lot of what I’ve done unsustainable. It’s very disappointing. I don’t think they purposely did it. But the unintentional consequences could affect whether Philadelphians have grocery stores or not. It literally could be that significant.”

And this notion, advanced by Kenney, that Brown and others are just heartlessly crying wolf? “The idea that any businessman would lay off workers when you don’t absolutely have to is preposterous,” he says. He’s not an opponent of Pre-K, so much as a proponent of thought-out economic growth policies. “I spend about 25 percent of my waking hours on education and workforce development,” he says. “I’m the Chair of the Philadelphia Youth Network and Vice Chair of the Pennsylvania Workforce Development Board. My whole life is about creating opportunity for underprivileged people, but this way of doing it is not a thoughtful way. Because if the parents lose their job but their kid gets Pre-K, you did not help them escape poverty.”

Brown has long held regular community meetings in the neighborhoods serviced by his stores. Invariably, he’d run across would-be customers who wanted more sophisticated and healthy fare than the typical urban grocery. Brown studied the success of Whole Foods and Wegman’s, and started to wonder: Why couldn’t their model work in Philly neighborhoods that haven’t had access to quality fresh food? He’d gotten to know enough customers over the years to know that a sizable number wanted healthy food — just like in the suburbs.

When he acquired the Fresh Grocer brand name, he decided to test the thesis, first with a store in Wyncote and now Wynnefield. He invested in fishmongers, in-store chefs, and all-star butchers; he stocked the shelves with organic options. He also studied the “Third Place” philosophy behind Starbucks, the notion that people yearn for communal spaces outside of the home and workplace at which to gather. That’s why Brown’s stores aren’t just stores — they’re community centers. Some have staff nutritionists, credit unions and health clinics. At Wynnefield, I saw an older man and a younger one — grandfather and grandson? — share some fire-grilled chicken in the open seating area … while setting up a chess board. In the midst of urban blight, his stores often remain unblemished by graffiti.

Politically speaking, the Mayor has done a deft job of making “Big Soda” into a modern-day “Big Tobacco” — cold, greedy, profiteers who exploit his constituents for private gain. But now that Brown is speaking out, Kenney might have met his match. Brown is harder to vilify than a giant soda company — because he’s actually been servicing Kenney’s voters for years, and because he’s been working on inner-city social justice issues just as long.

Make no mistake, Jeff Brown doesn’t just open super markets. He employs our citizens and he posits a way to think about what it means to be part of a community, which is why it’s so striking that the Mayor is critical of him. At one point, Brown takes me outside the store and points to the expanse of neighborhood before us. “This location, Wynnefield Heights, is very interesting to me,” Brown says. “It’s as diverse as you can get. It has low income and high income, it has African American, Caucasians. And yet, on the other side of the street, is Bala Cynwyd. It really is an interesting mix, and my belief is society works best when we all get along and work together. I think Philadelphia is a place that can do that.”

Jeff Brown is a fourth generation grocer who learned all he needed to know about business and life at the knee of his father, Lenny Brown. Lenny had a corner grocery at 40th and Girard. Jeff would watch his old man extend credit to the neighbor who had fallen on hard times, and he’d see him wipe a family’s slate clean when the breadwinner got sick or laid off. He saw how much his father cared, and he learned that that—caring about your neighbor — is what cities are all about.

“When you serve people in underprivileged areas, there’s a lot of tragedy and a lot of problems, and it’s hard to be with people, observing what they go through, and stand on the sidelines and say ‘Tough luck,’” Jeff Brown says. “You know what I mean? You gotta be a rotten human being to do that. The more you’re in the thick of things, it ends up changing you.”