Mayor Kenney’s blockbuster first-term initiative, a soda tax to fund pre-K (among other things), is most likely going to pass City Council tomorrow. The bill has changed significantly over the course of the budget cycle: What was once a three cents-per-ounce tax on sugar-sweetened beverages that excluded diet drinks is now a 1.5 cents-per-ounce tax on all sweetened drinks, diet included. (You can read the final bill here.) Council and the Mayor say that this lower, more inclusive tax will raise about the same amount of revenue as the original three cent proposal.

But if you think we’re all set to fund pre-K forever with this shiny new tax, think again.

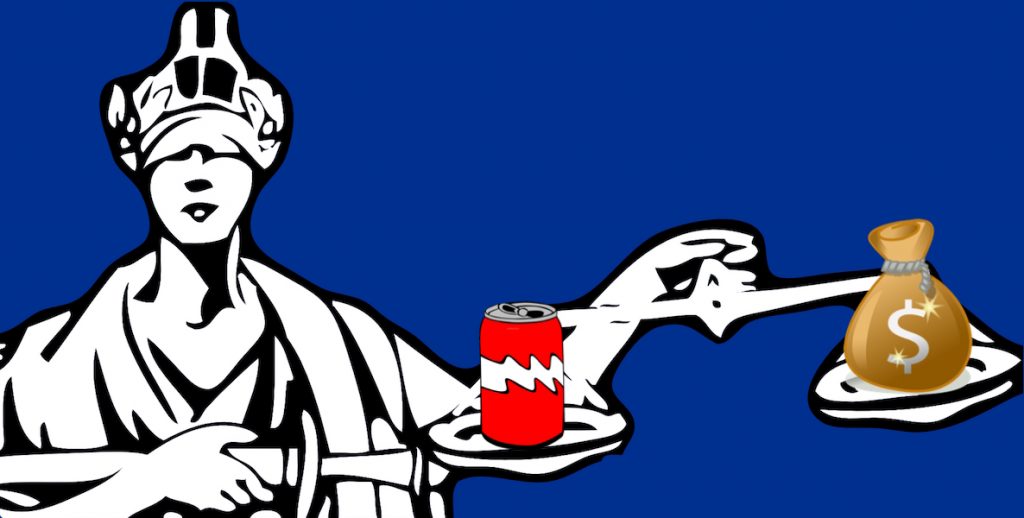

The soda industry, led by the American Beverage Association (ABA), has been fighting this since day one. They’ve spent over $1.5 million in advertising against the tax, in what now appears to be a failed effort. Try as they might to influence Council, they couldn’t do enough to block the tax. But they have one card left to play: a lawsuit against the City arguing that the tax is illegal.

Then it will be up to our courts to decide the ultimate fate of the soda tax.

Ok, so is the soda tax constitutional?

*Puts on black robe and powdered wig* Maybe. Both the City Solicitor’s office and the ABA released memos in the last few months arguing their client’s side of the issue. Essentially, there are two possible flaws with the law as written that could make it illegal and invalid. First, it may violate Pennsylvania’s Uniformity Clause. Second, it may be preempted by existing state law. And this morning, Ron Castille, former Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court—the body that may ultimately decide the fate of the tax— weighed in, declaring it unconstitutional.

What is this Uniformity Clause?

The Uniformity Clause of Pennsylvania’s Constitution requires all classes of goods to be taxed at the same rate. It’s the reason we can’t have a progressive income tax, and why business and residential properties are taxed at the same rate. It’s a pain in the ass, but for now we’re stuck with it.

Before diet drinks were included, this was a huge issue for the City to address. In Kenney’s original proposal, the exclusion of diet drinks would have made the uniformity argument very hard to overcome. After all, why not tax diet drinks as well as regular drinks? That’s no longer an issue.

But the Uniformity Clause isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. In reality, the same items can be taxed at different rates. For example, anyone who pays the Philadelphia wage tax knows that Philadelphia residents pay a higher tax on their income than non-residents do. And liquor purchased by restaurants is taxed differently than the exact same bottles purchased by you or me at the state store. These examples would seem to violate uniformity, but the actual requirement isn’t strict uniformity.

We know the soda tax will pass. We’re pretty certain the soda industry will sue, and that we’ll have to pay the price increase while waiting for the courts to decide the case. We don’t know whether or not the soda tax will be deemed legal.

For the product being taxed—here, sweetened versus unsweetened beverages—the City only needs to show that there’s a “legitimate distinction” between the two classes of goods. In other words, they need to say why there’s a good reason for taxing sweetened drinks and not unsweetened drinks.

The state’s sales tax structure has already done the work for them. In Pennsylvania, groceries are not subject to the six percent sales tax. However, sodas and similar beverages are subject to the tax. Kenney’s bill’s definition of sweetened beverages is strikingly close to the state’s definition (so close, in fact, that one wonders why Kenney didn’t use this definition in the first place). So if the state law’s classification is constitutional, then Kenney’s bill must be as well.

But the Uniformity Clause doesn’t just look at the product being taxed; it also looks at who’s paying the tax, and mandates that the burdens and benefits be fairly distributed. Going back to Philly’s wage tax, the reason that city residents can be taxed at higher rates is that they receive significantly more benefits of government service, such as police, fire, and streets than do non-residents.

A counterexample comes from a case out of Pittsburgh. There, Allegheny County (which, unlike Philadelphia County, contains dozens of cities and towns) passed a county-wide hotel tax to fund a convention center in downtown Pittsburgh. Since only Pittsburgh hotels would see the benefits from an increase in customers, the hotels in outlying cities were unfairly burdened with the tax, and therefore the tax violated uniformity.

This could be a problem for the soda tax. The Kenney administration insists that the tax won’t be borne by consumers, but by distributors. But unlike consumers, the distributors aren’t all located in Philadelphia; those that aren’t would have the burden of paying the tax, but not see the benefits of the programs it will fund, like pre-K. This seems to be analogous to the Pittsburgh case. On the other hand, since the tax only applies to the sodas actually sold in Philadelphia, the soda tax might be different enough to still be constitutional.

There’s enough wiggle room here that it’s conceivable that either side could win on this issue, and it’s hard to say that one side has a definite advantage over the other.

Preemption by state law

If you thought the Uniformity Clause was technical and obtuse, then, man, are you going to love the doctrine of preemption! The quick version is that Philadelphia has the right to tax anything it wants, as long as the state doesn’t already tax it. If the state does tax it, then Philadelphia is “preempted,” and needs special permission to create the overlapping tax. It’s kind of like when you were a kid and asked your mom for ice cream and she said no, so you went to your dad and he said, “Did you ask your mother?” Dad only gets to decide if mom lets him. Your mom is the state, and your dad is Philadelphia. Mom always wins.

Sales tax is a great example of preemption. The state already has a sales tax (six percent), but it gave Philadelphia special permission in 2009 to add an additional two percent. Similarly, the state in 2014 gave Philadelphia permission to tax cigarettes an additional $2 per pack on top of the state’s tax.

As noted above, the state already taxes soda (and similar beverages) under the sales tax, but it hasn’t given Philadelphia special permission to tax soda again. So it would seem that Philly’s soda tax is preempted. But it’s never that easy! The state taxes sodas at the retail level, not distributors. Philly’s soda tax would only tax sales by distributors, not retail sales. The City can argue that this distinction makes the difference. The beverage industry, though, will say the tax is effectively a sales tax because the consumers are going to pay it.

The City will go one step further, arguing that this is not technically a sales tax at all because the tax is calculated by volume, not price. The argument will be that sales taxes can only be based on the actual sale price of the item; the soda tax, in contrast, taxes the amount of soda distributed regardless of its sale price, and therefore is not a sales tax. The soda industry’s counterargument is that taxing the amount is just a stand-in for price, since soda tends to have about the same price per ounce. They’ll say that taxing by volume is a poor workaround, and that it still amounts to a sales tax.

As the Kenney administration insists, the tax won’t be borne by consumers, but by distributors. But unlike consumers, the distributors aren’t all located in Philadelphia; those that aren’t would have the burden of paying the tax, but not see the benefits of the programs it will fund, like pre-K.

Leaving the door open for the City’s viewpoint would seem to set a dangerous precedent. So too would declaring that a tax isn’t a sales tax if it’s by volume (or weight or some other crude, proportionate measure), as the City contends, rather than if it’s taxed based on sale price.

Again, this could go either way, and both sides will likely come up with arguments and counter-arguments that I haven’t thought of. And, at the end of the day, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court can do whatever they want. That’s why we elected them, right?

What happened in soda lawsuits elsewhere?

This is a battle that’s been played out before, although not yet in Pennsylvania. The two most notable cases are Berkeley, CA and New York City.

Berkeley famously passed the first soda tax in the nation in 2014. The soda industry didn’t sue in that case, and the law still stands, probably because they couldn’t find a worthwhile basis for a lawsuit under California law.

In New York City, though, the soda industry won a major court victory. In 2012, then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s Department of Health issued an amendment to the city’s health code banning the sale of sodas larger than 16 ounces. The soda industry sued and won. New York’s highest court ruled in 2014 that the soda ban was outside of the city agency’s authority, and was therefore unconstitutional and invalid.

Although there aren’t many examples to go on, one lesson is still clear: The soda industry will sue if they can, and will rely on technicalities if that’s what it takes to strike down a law. The outcomes of any case is dependent on the text of the law, how it was passed, and other laws of the state in which it was passed. So neither New York City nor Berkeley foreshadow what will happen to Philly’s tax.

Lawsuits are slow; would the tax be collected in the meantime?

The lawsuit in New York took about two years to resolve. That’s certainly not the longest-running case in American history, but a two year delay could mean that pre-K, and the other initiatives to be funded by the tax, would be in limbo until near the end of Kenney’s first administration.

Setting aside who’s likely to win the case, the most pressing question is whether the City will be able to collect on the soda tax while the case is pending. Assuming that beverage distributors play by the rules and don’t just refuse to pay the tax (which would put them on Councilman Allan Domb’s naughty list for delinquent taxes), they would have to obtain a preliminary injunction against the City to prevent it from collecting the tax until the case is settled.

If the soda industry wins a preliminary injunction, they won’t have to pay taxes, potentially for years, while the case plays out (although they would still owe all those back taxes if they lost). If they’re not paying taxes right now, then pre-K isn’t getting funded right now.

Fortunately for the City, Pennsylvania courts are unlikely to grant an injunction when deciding whether or not a tax is legal. Such injunctions are only granted where “necessary to prevent immediate and irreparable harm which could not be compensated by [money].” If a soda distributor pays the taxes for two years, it’s not going to shut down. And if they win the case, then the City will have to pay back all of those taxes; that’s very little harm to the soda industry, and what little harm there was could be adequately compensated by money.

Speaking of which: What do we do if the City has to pay back nearly $200 million in taxes if the soda tax is found to be unconstitutional?

Well, we certainly can’t take it out of the pension surplus. Maybe we can try something crazy that we know is legal, like, say, zero-based budgeting?

Holy crap that was a lot of info. Can I get a tl;dr version?

We know the soda tax will pass. We’re pretty certain the soda industry will sue, and that we’ll have to pay the price increase while waiting for the courts to decide the case. We don’t know yet whether or not the soda tax will be deemed legal—or if all of this politicking has been for naught.